|

by BOB DORAN

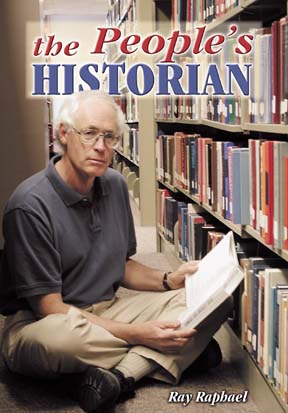

SINCE HE MOVED TO HUMBOLDT County

30 years ago, Ray Raphael (in

photo above) has been studying and

writing about history. He was never trained as a historian, perhaps

that's why his approach to the past has always been a bit different.

His first book, An Everyday

History of Somewhere, published in 1974, set the tone. It

is an examination of the people and events that shaped southern

Humboldt County -- a history "from the bottom up,"

told by everyday people instead of by the political and other

leaders who typically dominate our history books.

This weekend Raphael celebrates

the release of his ninth book, A People's History of the American

Revolution. While it is quite different from his first book,

the approach is the same. He offers a history from the point

of view of common people; in fact the book's subtitle is, "How

Common People Shaped the Fight for Independence."

![[A People's History of the American Revolution book cover]](cover0412-revolution.jpg) Raphael's

own everyday history begins in New York City. He lived there

until he was 18. Raphael's

own everyday history begins in New York City. He lived there

until he was 18.

"The day after I graduated

high school I headed west, pack on my back. I headed for the

wide open spaces," he said while relaxing in a comfortable

chair on his front porch in Redway last week.

After spending a summer backpacking,

he made his way to Reed College in Portland, Ore. His official

major was philosophy, but he said, "My real focus was on

being an activist.

"The first summer after

I started school I got involved in the Civil Rights movement.

I spent two summers in the South. First it was a project doing

voter registration and tutoring, going into integrated schools

in North Carolina. Then we integrated several public facilities

-- the swimming pool, the baseball park and the wrestling match.

Integrating wrestling was tough."

In 1962 he went south with the

National Student Association and in 1964 worked with the Student

Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, SNCC.

"It was Freedom Summer

down in Mississippi. I met Fanny Lou Hamer and was involved in

that process. That was the year three activists were killed,

two of them I knew."

His experience with SNCC led

to his first exposure to the writer, Howard Zinn.

"I read his book, SNCC,

the New Abolitionists. What was remarkable was the fact that

he got it right. This was a time when people could easily get

it wrong. There was usually a focus on leaders, Martin Luther

King this, and Martin Luther King that. His book was about who

the people in SNCC really were -- the field secretaries and the

daily work going to the plantations.

"Zinn captured the whole

spirit of the movement from the bottom up. I was impressed because

here was this academic who got it. Then he wrote this other book,

Why We Should Get Out of Viet Nam, and I was very involved

in the peace movement."

After he finished at Reed, Raphael

became a full-time activist working with "the Movement"

on civil rights issues and protesting the war in Viet Nam. He

got a master's degree at UC Berkeley, once again a philosophy

major -- at least on paper.

"I didn't take a single

philosophy course, but there was a guy in the department who

was an expert in Karl Marx, so I studied under him. I took all

of my courses in political science, but my master's was in philosophy.

Really what I was doing was getting the theoretical underpinnings

of radicalism and what it meant for political action."

Feeling trapped in academia,

Raphael followed the lead of his friend Rondal Snodgrass who

was teaching in an inner city school in Portland. (Snodgrass

is now living in Southern Humboldt. Until recently he was executive

director of Sanctuary Forest.) Ray went back to Reed long enough

to get a teaching credential.

Raphael returned to California

to teach high school and to resume his work as a radical. After

a few years he began to get frustrated.

"It was hard being part

of the Movement in the '60s. You had all of these ideas, yet

the war kept going on and the civil rights movement was getting

splintered, becoming hyper-radicalized and dysfunctional. There

wasn't much change happening."

Then along came "flower

power."

"A lot of us started thinking

about creating an alternative. Instead of trying to stop this

huge machine, let's try to create a better life. You remember

I had a pack on my back when I came from New York; I was looking

for wide-open spaces. The combination of a search for a better

life and wide open spaces led me to southern Humboldt."

Raphael moved to Whale Gulch

in 1970. He and two partners bought 20 acres and got back to

the land.

"We collected wild foods

and grew some vegetables, raised chickens and rabbits. It was

pretty basic. Our land payments were $105 a month, but I had

put up the down payment to get a road in there, so my part was

$25 a month.

"I lived in a 12 by 16-foot

cabin for five years, totally off the grid, no electricity or

anything. This was presolar power so we had those smelly kerosene

lamps. It felt romantic until we did it for a year or two. Then

it was just suffocating."

All those years in college were

not completely forgotten. Raphael began a research project of

sorts, an exploration of the history of his own neighborhood.

"Being a curious guy I

wanted to know more about this place I'd moved to," he recalled.

"I looked in the library and found nothing. That was kind

of frustrating. So I started talking to old-timers and learned

a lot more. I met a guy named Harry Roberts, who had been raised

by Yuroks. He was kind of an heir to the Yurok high men's medicine."

Raphael and a group of friends

would visit Roberts on weekends to learn about the ways of the

past.

"We would take plants down

to him and ask, `What's this?' How did the Indians use it? We

learned how to grind acorns and all sorts of skills. We learned

the Native American traditions in an oral fashion, and then I

would go back and compare it with Kroeber. (Alfred Kroeber wrote

Handbook of the Indians of California.) It was so much

more alive the way we learned it orally."

This was around the time that

a group in the hills of Georgia put out The Foxfire Book,

an oral history with lessons on log cabin building, snake lore,

mountain crafts and food, and "other affairs of plain living."

"I was into doing some

sort of local Foxfire thing," said Rafael. "That's

how An Everyday History of Somewhere was born. I wanted

to explore the historical meaning of this place. As I started

looking, I found there was nothing written down. All the history

focused on Eureka and there was nothing about the backwoods.

![[Everyday History of Somewhere book cover]](cover0412-everyday.jpg) "So I decided

I should write a book, to do that I had to learn how to write.

All I knew how to write was college papers. I had to get the

therefores and howevers and convoluted sentence structures out

of my writing rhythm and learn how to write simply. "So I decided

I should write a book, to do that I had to learn how to write.

All I knew how to write was college papers. I had to get the

therefores and howevers and convoluted sentence structures out

of my writing rhythm and learn how to write simply.

"The key is I had a book

to write and I learned by doing it. I had this vision of everyday

history. And half the book was oral history, so I was transcribing

the spoken word. Listening to the words and transcribing affected

my writing. Ever after that people would say I have an accessible

style. I think it's because my writing is like what I hear."

Manuscript in hand, Raphael

went off in search of a publisher.

"I carried a couple of

copies down to San Francisco following leads. One was Rolling

Stone's Straight Arrow Press. They wanted to do it. But then

I took it to this paper called Clear Creek, a small journal

that only lasted a couple of years. Someone had told me they

were getting into book publishing.

"The guy who ran it --

Bill Barish, he's now a very well known writer -- said, `This

is great.' He sat up all night reading it and he wanted to publish

it. I was stoked. Then two weeks later he calls and tells me,

`I have bad news: Clear Creek's folding. But I happen to be a

literary agent, too. And I have a friend at Knopf in New York

and I'm going to send it to him.' That's how Everyday History

ended up with Knopf, which is probably the most respected publisher

in the country. What a stroke of luck."

Having established himself as

a writer, Raphael began contributing pieces to a number of publications,

in particular to the San Francisco Chronicle. His second

book, Edges: Human Ecology of the Backcountry, was a collection

of those articles.

"Then for my next two books

I took that oral history approach and applied it to the two most

controversial issues we have up here -- timber and marijuana."

Timber Talk: The People and

Politics of Timber was a collection

of interviews.

"My idea was to stop the

rhetoric and preconceived notions and get down to the people

level. Let's see what people really think. So instead of talking

to someone and quoting a little paragraph, I let them tell their

whole story. Whether you have an environmentalist or a timber

company executive, they tell their story and have their place

in the complete narrative."

Raphael faced some resistance

when he began work on his next book, Cash Crop: An American

Dream?, a look at the southern Humboldt marijuana trade.

![[Cash Crop book cover]](cover0412-cashcrop.jpg) Sensationalized stories in newspapers

and magazines had made the pot growers leery of any scrutiny.

The media invariably got some part of the story wrong. Sensationalized stories in newspapers

and magazines had made the pot growers leery of any scrutiny.

The media invariably got some part of the story wrong.

"That's one of the reasons

I wrote the book," said Raphael. "I had written these

other books and people kept asking when I was going to write

a book about marijuana. I'd say, `I'm not going to touch it.

I live here. What am I crazy?'

"What happened was every

year come September the Chronicle came out with their

headline story, the Sacramento Bee would do the same.

The New York Times wrote, "The streets of Garberville

are lined with Mercedes," -- that's a direct quote. This

was happening year after year in the early '80s. Finally this

guy came out with this outrageous novel, Outlaws in Babylon,

with tales of naked women cleaning pot. And on the cover of Newsweek

there was a picture of a guy with a mask and a gun; 60 Minutes

came out. The idea of keeping anything secret was ridiculous

and the picture that was emerging in the media was full of incredible

fantasies and lies.

"I said, `Let's just tell

the real story as it is, from the participants. I took a deliberately

flat approach, not advocating anything or opposing anything.

I just told the story and included all the actors. I have the

dope growers and the kids of dope growers, the head of CAMP (Campaign

Against Marijuana Plantings) and the high school principal, the

town businessmen.

"Most of the people really

appreciated the balanced approach, but there were probably 10-20

percent of the people who were inside the grower's community

who were outraged that I would say anything. They thought it

should all be a secret. They wouldn't even read it."

Raphael applied a similar approach

-- using first-person sources -- in The Teacher's Voice.

When his son was moving from boyhood to manhood, he wrote The

Men From the Boys: Rites of Passage in Male America. He revisited

timber issues in More Tree Talk, and wrote a detailed

biography of a southern Humboldt pioneer, Little White Father:

Redick McKee on the California Frontier.

Five years ago he began work

on a different sort of history, once again seeking out first-hand

stories of participants. The result was his new book, A People's

History of the American Revolution.

"It's goes all the way

back to the Everyday History -- all of my books are based

on the lives of individual people and how they experience reality.

It gives credit to their lives no matter what side of the political

issue they're on."

Of course there is a major difference

between collecting first-person oral history from living people

and investigating something that happened over 200 years ago.

How do you go about digging out the everyday history of the American

Revolution?

"It was a major challenge,"

said Raphael. "That's why this book took five years to write.

You basically have to comb all the written sources. There are

different levels of what you come up with."

What he searched for were the

stories of "common people."

"Common people are those

without the special privileges that accompany wealth, prestige

or political power. That includes just about everybody except

the elite."

A major obstacle in finding

the stories of the non-elite is the fact that 230 years ago most

were illiterate.

"Or they were barely literate.

Some could write a little bit, but if they wrote letters they

were not always preserved by secure family structures and housed

in safe places in mansions. So we have precious little to go

on. I had to search far and wide to find what remains.

"There were two slaves

who escaped to the British and became preachers. Their stories

were told in these religious journals in 1790 or something. If

you can locate these journals, you can get them on an interlibrary

loan. Sometimes the material is on microfilm. Sometimes it's

in an old book.

"Some of the stories have

been reproduced in book form; like, there's a marvelous one written

by an Iroquois warrior called Black Snake. He gives the inside

story about how the Revolutionary War affected the Iroquois.

"He talks about negotiations

that took place when both the Americans and the British were

courting the Iroquois trying to get them to join their side.

He tells us about the deliberations among the warriors, how they

reacted. Some wanted to join the British, others didn't. They

preached caution. But then those who wanted to join called the

others cowards and no warrior could be called a coward. So for

that reason they joined the war. We learn about this from the

inside."

Raphael made several trips back

East but for the most part he relied on the wonders of the interlibrary

loan system.

"The Humboldt State University

library deserves a lot of credit for this book," said Raphael.

His challenge was to figure out what source material to ask for.

"One footnote would lead to another and, as often as not,

authors only use a small portion of original source material.

The trick is to trace the material all the way back."

The picture he paints in A

People's History of the American Revolution is a far cry

from what we learned in high school history class. We find that

the American Revolution was much more than George Washington

leading a band of patriots in three-cornered hats against red-coated

Tories. Poor farmers did not necessarily side with rich landowners,

slaves did not necessarily fight alongside their masters. The

Native American population had hard choices to make. No one had

the option of remaining neutral.

"This is history from the

bottom up. Just as I do in all my books, my starting point is

to treat individual common people respectfully. How do they see

history? How do they try to participate in it? How do they do

what's best for themselves, for their group and their family?

We see things through their eyes.

"The key thing you see

through it all is that every single person during those time

had to become a political actor. They had to figure out how their

actions would be perceived, what the consequences would be, what

actions would best help them survive, what actions would best

help them promote their ideals or in many cases their own liberty

or economic well-being.

"There are so many myths

that are immediately shattered. Take for example the beginning

of the war, `The shot heard 'round the world.' In fact, in 1774

the common farmers of Massachusetts engaged in a total revolution

where they threw out every British official. The British had

to resign their positions or retreat behind British lines in

Boston. You never hear about this revolution of the common people."

After writing the book on speculation,

Raphael found a publisher, The New Press. All the pieces were

in place except for a title.

"I had all kinds of titles

that didn't quite work," he said. "Whenever anybody

would ask, `What are you working on?' I'd say, `Oh, it's a people's

history of the American Revolution, or it's a history of common

people in the American Revolution.' We couldn't call it `The

People's History of the American Revolution' because that sounded

too much like Zinn's People's History of the United States.

It would be like pirating his title."

While it wasn't in the original

plan, Raphael ended up using the exact title -- with Zinn's blessing.

"New Press published a

school book version of Zinn's People's History. They sent

the bound galleys of my book to Howard for a cover quote.

"At that point we still

hadn't settled on a title. I think we were down to something

generic like `Voices of American Revolution.' He read the book

and said he thought it was the best book he's read on the revolution.

On a deep level he understands my approach, that I don't take

a doctrinaire standard leftist approach.

"Howard talked to one of

the editors at New Press and they come up with this idea to do

a whole `People's History' series, where a number of writers

will explore issues in depth from the standpoint of common people.

This is volume one of the series. The other volumes are yet to

be done. This one will serve as a prototype. Howard is the series

editor. He's working with my editor at New Press, Marc Favreau,

to come up with some new authors for the series."

New Press has not determined

what the next in the series will be. A "People's History"

of California has been suggested along with several other ideas.

Whatever the choice, Raphael will not be the author. He already

has commitments for several other projects. He's finishing up

a book that focuses on the 1774 overthrow of the government by

the farmers of Massachusetts.

"After that I'm trying

to get a local history going with the Humboldt Historical Society.

Jerry Rohde and I are working on a two-volume history of Humboldt

County. If you know his work, you know Jerry likes to write about

things place by place. We realize that our approaches are different

enough so that we'll need to do two different books. The subtitle

of mine will be `People and Time' his will be "People and

Place.' Jerry likes to describe it in weaving terms, as the `warp

and woof' of local history."

![[Photo of Howard Zinn]](cover0412-zinn.jpg) Thursday, April 12, 6-9 p.m.,

Ray Raphael will sign copies of his book at Orange

Cat Goes to Market in Garberville. Friday, April 13, Thursday, April 12, 6-9 p.m.,

Ray Raphael will sign copies of his book at Orange

Cat Goes to Market in Garberville. Friday, April 13,

6-9 p.m., he will

be at Northtown Books, 957 H St., Arcata. Thursday, April

19, at 8 p.m., Howard Zinn (photo

at left) speaks at HSU's East Gym

as part of the Associated Students Lecture Series. Free admission.

For more information contact the University ticket office, 826-3928.

IN

THE NEWS | GARDEN | ARTS! ARCATA | CALENDAR

Comments? E-mail the Journal: ncjour@northcoast.com

© Copyright 2001, North Coast Journal,

Inc.

|