|

IN

THE NEWS | CALENDAR

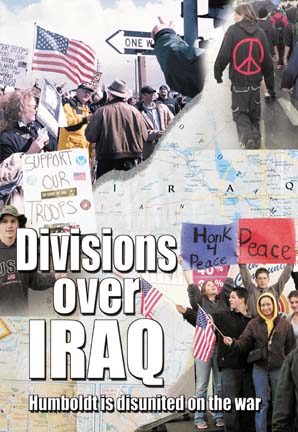

by KEITH EASTHOUSE

Sidebar: High

school students march for peace

But some express support for the war

WITH AMERICAN AND BRITISH forces

making dramatic gains every day -- and with the possibility that

Saddam Hussein and his two sons were killed in a bombing raid

Monday -- the debate over the war in Iraq is fast becoming moot.

Like it or not, a military government

headed by a United States general will soon be calling the shots

in the battered Middle Eastern country, much like the provisional

government headed by Douglas MacArthur that was set up in Japan

at the end of World War II. After a six-and-a-half-year occupation,

MacArthur and his assistants packed their bags and left, leaving

behind something new: a fledgling democratic government in a

country without any democratic traditions.

That government persists to

this day, as do the American military bases established during

MacArthur's reign, the bulk of which are concentrated off the

Japanese mainland on the island of Okinawa.

A similar future is envisioned

for Iraq, although there are critical differences between that

country today and Japan in 1945 -- a key one being that the Japanese

people accepted MacArthur because he had been endorsed by the

Japanese emperor; there is no such figure in Iraq to give whoever

heads the military government there a similar imprimatur. Also,

the Japanese had surrendered unconditionally, while the Iraqis

are not likely to; and Iraq, riven by age-old ethnic and religious

animosities, is a much less cohesive country than Japan was.

All of which suggests that the

peace in Iraq may be more difficult than the war. Nonetheless,

there's no disputing that this is a watershed moment in world

history: America now has a new military beachhead in the Middle

East. There's also no disputing that the way in which the Bush

administration achieved this has been controversial both abroad

and at home. Here in Humboldt people are still struggling to

come to terms with what has happened in the past days, weeks

and months. And while virtually everyone supports American troops,

people are divided about the wisdom of this war, not to mention

its legality and morality. What follows are brief snapshots of

the views of some community members.

"I am not for war,"

said MariLou Renner. "But I feel peace comes at a price."

Renner should know. Her oldest boy, Cameron, is in Iraq right

now. He's a logistics officer in the 3rd batallion, 2nd Marine

division. She and her husband, Mike Renner, owner of Renner Petroleum,

believe that Cameron is presently somewhere south of Baghdad.

They talked to him on the telephone on March 15, when he was

in Kuwait, prior to the invasion. And he wrote them a letter

two days later. Since then, silence. Which isn't really surprising.

As MariLou Renner put it: "There's no way he can take time

to sit down and write a letter because he's fighting for his

life."

That, of course, is just it.

Her son is in harm's way, and like every loving mother her instinct

is to protect him, never mind that he's a fully grown, 25-year-old

adult. Given the fact that he's on the other side of the world,

she can't. So MariLou Renner is having to endure an exquisite

kind of torture that only the parents of soldiers at war -- perhaps

only the mothers of those men and women -- can fully understand.

"I've had a nervous kind of feeling before, but I don't

think I've ever had this kind of feeling before. It's very, very

nerve-wracking. I just get a feeling in the pit of my stomach.

It's almost like my heart is being torn out." At another

point she said something that revealed a fundamental truth about

parenthood: No matter what the situation, you feel responsible

for your children. "I feel like I'm taking my first son

and sacrificing him," Renner said. "In a way, every

day is a death."

[left, MariLou

Renner and her son Cameron]

Renner and her husband have

had good cause to be worried: Cameron was involved in some of

the fiercest fighting of the war to date, the firefights in and

around Nasiriya, an urban center in central Iraq. She knows that

he survived because a colonel recently sent an e-mail to his

own wife at the Marine's Camp Lejune base in North Carolina that

said everyone in Cameron's division survived; the colonel's wife,

in turn, passed along the e-mail to the troops' wives.

Cameron, a graduate of St. Bernard

Catholic School in Eureka, met his wife, Sarah, at Oregon State

University in Corvallis, where they were both students. An all-around

athlete and student body president in high school, Cameron studied

business and animal science at Oregon State and had planned on

being a large animal veterinarian. But then an aptitude test

he took in college showed that he was strongly suited for the

military, and Cameron switched direction.

"It was a shock to my life

when he went into the military," his mother recalled. "But

when I looked back on him as a little child, I wasn't really

surprised. He was always a real spiritual child, very loving

and compassionate. But he always had a really determined, strong

side, too."

Cameron has a child of his own,

a 9-month-old girl named Scarlet. In his letter in March he talked

of missing her, and made reference to the fear many soldiers

have: that the things they see and have to do in combat will

somehow make them fearsome to their loved ones when they return.

"I hope she is not afraid of me or anything," he wrote.

Cameron's mother's greatest

fear is obvious. Given the military's practice of personally

informing loved ones of combat fatalities, Renner said that if

someone were to knock on her door in the middle of the night

for no good reason, "I would probably choke them."

She also expressed frustration at anti-war protesters, who have

been fairly visible in both Eureka and Arcata. She said they

are "angry," not peaceful, and have a "political

agenda."

"I don't have trouble with

the Women in Black," she went on, "because they are

truly praying and standing for peace. Praying for our boys and

peace -- that's a peace march to me."

Bud Tillinghast, a retired United Methodist minister, is opposed

to the war. But he said he also supports the troops.

"People who support the

war assume that people who are against the war are not concerned

for our American troops. But attempting to divide the community

in terms of anti-war and anti-troops is a false dichotomy that

only hurts everyone.

"Religious leaders who

have to deal with families who have lost sons and daughters are

sensitive to the concerns of families for the safety of their

children," he added.

Tillinghast, along with about

30 other local religious leaders, endorsed an advertisement for

the March 15 "peace march" in Eureka that appeared

in local newspapers. Now he said he wants to join with local

veterans' groups "to plan a welcome back for our troops

when they return."

The minister said his opposition

to the war stems from his belief that it is immoral. For a war

to be just, he said, "it should be the last resort."

In this case, President Bush did not try to avoid war; quite

the opposite. As a result, the whole diplomatic saga at the United

Nations, in Tillinghast's view, was nothing more than a sham.

"Despite taking this to the U.N., a decision had already

been reached by the administration and the neo-conservatives

to change the complexion of the Middle East."

Tillinghast said the war was

immoral for another reason: It violates the principle of proportionality

because the United States is using overwhelming force on a comparatively

weak nation.

Tillinghast said he genuinely

believes the president is what he proclaims to be: a devout Christian.

But he said Bush is a Christian "in the tradition of the

Crusades, where the world is divided between those who are good

and those who are evil.

"For me, the line between

good and evil goes through the human heart; it is not an external

thing. Therefore, we are all involved with good and evil. With

good intentions, I can do evil things."

Abdul Aziz, a Humboldt State University business professor

who was born in Pakistan, is also troubled by this war. Doubly

troubled, actually, since his faith -- Islam -- demands two things

of him: loyalty to his country, which in his case is America

since he is a U.S. citizen; and loyalty to all Muslims everywhere.

"There's a saying of the

prophet Mohammed," Aziz said. "Two Muslims are like

two fingers of the same hand; when one hurts, the other will

feel the pain.

"So the Muslim community

is torn," Aziz went on. "Muslim-Americans are feeling

the pain right now because so many Iraqi civilians are getting

killed. But at the same time we are citizens of the U.S.

"It's very hard,"

he added. "How do I support the troops when I don't like

the war? I keep praying."

Like Tillinghast, Aziz believes

President Bush deliberately pushed for war. He also expressed

deep skepticism about one of the justifications offered by the

president: the need to deter future terrorist attacks on the

United States.

"This preemption can lead

us to a path of fighting many more wars. It can also encourage

other strong nations to start wars with weaker nations."

Aziz expressed concern that the example of the war in Iraq could

cause India to attack his native Pakistan over the Kashmir, long

a disputed area between the two nuclear-armed South Asian countries.

He also said that Israel could look to the Iraq war as justification

for taking preemptive action against Palestinians to prevent

suicide bombings. Finally, he said many countries in Africa,

a chronically unstable area, could use the doctrine of preemption

to wage war on their neighbors. "The preemption principle

itself could lead to world chaos," Aziz warned.

Like Aziz, Saeed Mortazavi is

a professor in the business school at HSU and a U.S. citizen.

Unlike Aziz, he is an Iranian by bir th,

and, as such, is worried that his home country might be America's

next target. th,

and, as such, is worried that his home country might be America's

next target.

For one thing, Iran shares a

lengthy border with Iraq. For another, Iran is one of three countries

-- along with Iraq and North Korea -- that President Bush has

described as comprising an "axis of evil."

Mortazavi has no love for Iraq

or Saddam Hussein. "This is a regime that fought against

Iran for eight years [in the 1980s] and killed about a million

Iranians." Mortazavi pointed out something else: The United

States assisted Hussein in that war, both in terms of intelligence

and in terms of military technology.

Mortazavi said the warnings

the Bush administration issued last week to Syria and Iran about

coming to Iraq's aid are merely the latest in a string of negative

statements directed at Iran. Before Iran was part of the axis

of evil, it was deemed a rogue nation by American officials.

Mortazavi said that if derogatory

characterizations of a country are used to prod the government

in power to move in the right direction, that's one thing. But

if they "are used in a military sense to dehumanize the

country so it can become a military target, then there is a significant

problem with that."

Mortazavi said "there is

no good justification for military action against Iran.

"Iran is a developing democracy.

Iranians should be given a chance to reach their own democratic

solution without the intervention of other countries."

Jerry Partain bristles at the suggestion that the United States

is on the brink of a binge of conquest. "I can't go along

with people who say we are at the beginning phase of an imperialist

mode. It makes no damn sense.

"I don't see any evidence

or believe that the United States is ready to go into North Korea

and Iran," he added.

He said attacking Iraq was justified,

in part, because Saddam Hussein is such a cruel tyrant. Because

of America's might, he said it would have been less defensible

to have done nothing and allowed him to remain in power. "I

don't see how we could keep from doing something given the way

he's abused his own people. " "

He also doesn't think, as some

do, that the real motivation behind the war is to gain control

of Iraq's huge oil fields. "Hell no," he said when

asked. "We could have taken all the oil fields we wanted

in `91 [during the Gulf War] when we had 200,000 troops over

there."

Partain is a retired HSU forestry

professor. He served as the head of the California Department

of Forestry and Fire Protection from 1982 to 1989. He has traveled

extensively, visiting 64 countries, and is one of the more articulate

conservative voices in Humboldt County.

He said he was not surprised

at the resistance the Bush administration encountered at the

U.N. in the weeks leading up to the war. "That's been the

problem with the U.N. all these years. They talk a lot. They

write a lot. They spend a lot of time in hotels and bars. But

they are very shy on doing anything."

He said the opposition had much

to do with jealousy of American power, particularly on the part

of the French. "That's what was really goading them. They're

descending rapidly on the scale of real producers and they don't

like it." Partain said jealousy is also the root cause of

Arab resentment toward America.

But then won't attacking Iraq

fan the flames of resentment further and produce, as the Egyptian

leader Hosni Mubarak put it, "a hundred Bin Ladens?"

Partain said no, that American

strength would deter attacks. "They'll be less likely to

attack a strong horse," said Partain, who believes that

avoiding problems is what causes things to fester. "The

Clinton administration avoided lots of problems and things got

worse." One thing Partain said the Bush administration shouldn't

avoid is the Israeli-Palestinian issue.

"We need to get Israel

to accept a Palestinian state and get that established. That

would do more for stability in the Middle East than anything

else."

Paul Blank, an HSU geography professor, is perhaps the rarest

of birds in this debate: someone who, by his own account, is

on "both sides of the issue."

A fluent Arabic speaker who

lived in Cairo in the 1970s and 1980s, Blank is both "horrified

by the horror of war and the way the administration has run roughshod

over the international system," and "hoping against

hope that the war will effect change for the good in a situation

where the status quo is unacceptable."

Like Partain, he believes that

the Bush administration must now follow up and resolve the festering

Israeli-Palestinian conflict. "I'm not optimistic, but I'm

prepared to be pleasantly surprised."

Melanie Williams, an HSU political science professor, said that

the Iraq war is one more example of a growing divide among Americans

that can be traced to the disputed 2000 presidential election.

"George Bush says he's a unifier, but he keeps renting us

asunder." Whether it's the war, his budget proposals, civil

liberties, or international agreements, the president through

his actions keeps "showing the deep ideological divisions"

within the country.

Mike Harvey, county chairman

of the Republican Party, said "Frankly, it's not the time

to debate the war, but a time to support and send prayers to

our troops and their families. In fact, it's a time to send prayers

to the millions of innocent Iraqi civilians."

Eureka Mayor Peter La Vallee,

who opposes the war, said

the whole debate about Iraq has left a sour taste in his mouth.

"I'm tired of being told that the federal government has

all the answers and that I'm unpatriotic if I question [the war]."

David Meserve, an Arcata city council member who believes the

United States is bent on economic and military domination of

the planet, said he's felt a real sense of "powerlessness

and despair" since the war broke out.

He said he's particularly bothered

that Americans "are getting so hated in the rest of the

world.

"I don't feel as safe to

travel as I used to," Meserve said. "I feel like I'm

going to have to wear a sign on my back saying `I'm an American

but I disagree with my government.'"

Hugo Papstein, owner of two local talk radio stations -- KINS

and KWSW -- that feature Rush Limbaugh, said the vociferousness

of anti-war protesters in the Humboldt Bay region is misleading

-- most people, "a silent majority," are for the war.

"The people I talk to are certainly supportive of the war

effort and understand why it was necessary," Papstein said.

He remarked that he saw an "awful lot of support" at

the recent jazz festival. "There were standing ovations

every time a patriotic song was played," he said.

High

school students march for peace

But some express support for the war

by

BOB DORAN

ON A CLOUDY MORNING LAST WEEK,

just after the end of first period, a group of students began

assembling in front of Eureka High. American flags were pulled

from backpacks; a few kids held hand-lettered signs. One identified

the group as "EHS Students for peace." Another asked,

"How many lives will it take to end this war?" Yet

another boiled the issue down to a single word: "Death?"

Within minutes about 100 teenagers

set out en masse, walking briskly toward the county courthouse.

At the front of the crowd, Brandon Moore, age 16, one of the

students who organized the walkout, held a red sign marked with

a large peace symbol.

"I felt that we needed

to do something to show that the student body has a voice,"

said this clean-cut sophomore, who was wearing a tie. "We

need to say how we feel to show people what we want for our generation.

We want peace."

[right, Eureka

High students march down J Street.]

When the school administration

got wind of the walkout they proposed an alternative -- a school

assembly where students could air their views on the war.

Moore said he and the other

organizers felt the administration was "trying to downsize

our voice and our opinions. It seemed like they weren't taking

us seriously and wanted to control what we wanted to say."

When administration officials

saw that the students weren't going to back down, they circulated

a memo warning that anyone who left class would be punished.

"If I get in trouble I'll accept it," Moore said. "If

I get suspended I'll pin the notice on my shirt and let people

know that I got in trouble for what I believe in."

Moore said he hoped the assembly

would still take place. "We want to have student speakers

pro and con, plus a panel with speakers from Veterans for Peace

and Women in Black along with speakers from recruitment offices

and local people who have family members over in the war right

now. We want students to be able see what the different opinions

are and maybe learn something that might further their knowledge.

"We can't just sit back,"

he went on. "What's happening right now will affect our

lives when we grow older."

As the students made their way

down J Street, one marched apart from the rest. Matt Knudsen,

a junior dressed in desert brown camouflage pants and a USA sweatshirt,

held a sign saying "Support Our Troops." A campaign

button on his hat declared his support for President Bush and

Vice-President Cheney.

"I'm protesting the protesters,"

he explained. "I didn't want to cut class, but somebody

has to be out here to protest what they're doing. I think we

need to support America, and support our troops, even if you

don't agree with the war. The troops are out there defending

our freedom and the freedom of the Iraqi people."

Knudsen assured me that plenty

of students at Eureka High support the war. As if to confirm

that, a girl came up and said she was in favor of military intervention.

"People need to see both sides," she declared.

In

her mind the war in Iraq is a matter of self-protection. "The

Iraqis are making biological and chemical weapons. I believe

they could release them all over the United States. It'll be

just like we're animals locked in the pound being put to sleep.

We couldn't escape them," she said with fear in her voice. In

her mind the war in Iraq is a matter of self-protection. "The

Iraqis are making biological and chemical weapons. I believe

they could release them all over the United States. It'll be

just like we're animals locked in the pound being put to sleep.

We couldn't escape them," she said with fear in her voice.

When asked her name, she said

she wanted to remain anonymous. "Both of my parents are

against the war," she explained. "I don't want to get

in trouble."

[left, Matt Knudsen

shows his support for the troops.]

The group assembled on the courthouse

steps for a series of speeches. Student Shamara Wiley started

things off with a call for understanding, reading a speech adapted

from one she delivered at the March 15 peace rally in Eureka.

"I draw most of my inspiration

for Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.," she began. "I'm an

advocate for peace and non-violence. The only way we can stop

the war and stop violence is to change the way we perceive others.

If we perceive others as inferior then it makes it easier to

oppress them. If we perceive others as evil, it makes it easier

to kill them. We must begin to see others as equals, as brothers

and sisters."

At one point two students who

had not been on the march brandished signs with pro-war messages:

"Bombs over Baghdad" and "Turn Iraq into a parking

lot." When the crowd began to rumble with jeers, Moore silenced

them saying, "Respect their opinions. They have the right

to speak."

A furious hailstorm soon pummeled

the crowd, forcing many to seek shelter under a courthouse overhang.

"I'm not part of the protest,

I'm for [the] war," said Jessica, a 15-year-old sophomore,

over the cloudburst. "I think Saddam Hussein is a very bad

leader; his people are afraid of him. So I think we should defeat

Saddam Hussein. He has no right to hurt his people that way."

"Most of the people that

we fought so far just gave up because they're afraid of Saddam

Hussein," added her friend Aubrey, also 15. "They don't

want to die for him."

So are we fighting the war to

help the Iraqis? "Not really," said Aubrey, turning

pragmatic. "We need the oil. If we don't fight this war

they'll find some reason not to give it to us."

The hail dispersed most of the

crowd; some sought warmth inside the courthouse and used their

cell phones to try to find a ride back to school. Outside, the

remaining protesters moved to the street corner where they waved

signs urging passing motorists to honk for peace. A couple of

students battled playfully with hail "snowballs."

The die-hards were still gathered

in a small crowd. Moore stood in the middle clutching what was

left of the "EHS Students for Peace" sign. Soaked by

the rain, most of it had fallen away. All that remained was a

small rectangle that said "Peace."

IN

THE NEWS | CALENDAR

Comments?

© Copyright 2003, North Coast Journal,

Inc.

|