|

IN THE NEWS | ARTS! ARCATA | CALENDAR

by BOB DORAN

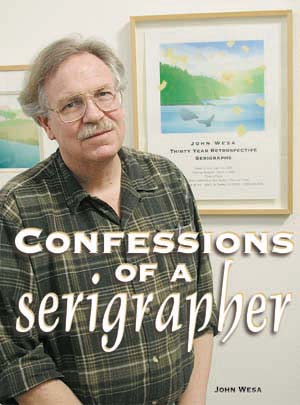

Photos courtesy of John Wesa WHAT IS SERIGRAPHY? | THE 3-D PERSPECTIVE

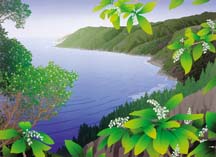

WORKING OUT OF A STUDIO BEHIND his McKinleyville home, John Wesa creates limited edition serigraphs, silk-screen prints with veils of color layered to depict an idyllic vision of pristine landscapes, radiant flowers -- a world in harmony. Wesa has been making art in Humboldt County for three decades. A retrospective exhibition celebrating his work opened Saturday at the Morris Graves Museum of Art. In addition to a roomful of prints in the William Thonson Gallery, the show includes a collection of Wesa posters in the Floyd Bettiga Gallery, downstairs in the Graves. One wall of the Thonson is dedicated to a series he calls "Terra Incognito," pieces he did for his master's thesis at Humboldt State. As he assembled the work in his studio the week before hanging the show, Wesa looked back with a critical eye. He realizes the prints did not communicate everything he wanted them to. "The title, `Terra Incognito,' means hidden landscape. The work was kind of circumscribed. It was OK. I think it's really beautiful. It shows the skills I had learned, but it had a missing component." While he can't verbalize what that "missing component" was from his early work, he knows he eventually found it. He knows from the response to his subsequent work. "There is something there. But if I talk about it too much, it ruins it. I don't really know how I do it, but I hear from other people what they get. And I like that exchange. I put my work out there and you tell me what it is. "There is a color, a me ter and a flavor in the way I do things that resonates with people. People get a peaceful, calm feeling, and I think that's antithetical to a lot of things that are out there, antithetic to what many people think art should be. ter and a flavor in the way I do things that resonates with people. People get a peaceful, calm feeling, and I think that's antithetical to a lot of things that are out there, antithetic to what many people think art should be. "I'm not trying to work out childhood problems or express the pain in my life. What I'm trying to do is take you somewhere and say, `Let's look at the sky,' or `Let's go over here for a minute and think about the way this leaf is in this light.' It's just about that. And it's about taking time to listen to your own heartbeat. "You know, in art school they do a great disservice to people. It's the easiest assignment come off with what's inside of you. "You know what's inside most people: a lot of darkness. What good does it do? I know that we all have flaws -- we all have character problems -- but do we have to celebrate them? I'm not ready for that."

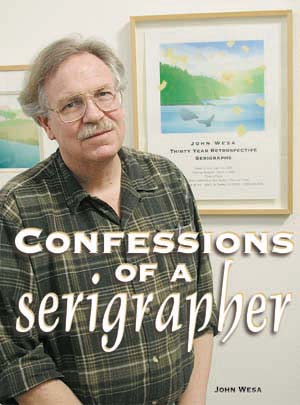

John West in his McKinleyville Studio. W esa comes from South San Francisco, "The Industrial City." After finishing high school in 1967 he briefly attended the nearby College of San Mateo. The counterculture was in full swing and the San Francisco Bay Area was the epicenter. "Those were heady times," said Wesa. There was a war on. Free speech was a hot campus issue. "At San Francisco State they dropped tear gas on campus. I just didn't want to be there." And he was tired of the pace in the city. "I didn't have the patience to live there; too many traffic jams." The next year he transferred to Humboldt State, partly because it was affordable -- "I only had so much money to go to school" -- but also because "It was peaceful up here." His initial plan was to study pottery -- and he did with the master, Reese Bullen. But as an art major, he was enrolled in a wide variety of classes. He learned photography from Tom Knight, graphics from Bill Thonson, printing from Bill Anderson. "I really liked art and printmaking, but I also liked writing -- and film was exciting for me." He finished his undergraduate work in 1971, earning a bachelor's degree in art with an emphasis on printmaking and cinema. He decided to pursue filmmaking, even though it meant leaving Humboldt. "I had done pretty well at it. I did a few short subjects and one got into a film festival in San Francisco, an adaptation of a Franz Kafka story, `The Fly.' Between that, my writing and another short subject I made, I got into film school, got a partial scholarship to California School of the Arts in Los Angeles. I was in love with film -- but once again, I was in the city. It didn't work out." Less than a year passed before he had dropped out and returned to Humboldt County. "I came back up here: I didn't know what I wanted to do. I worked at the Eureka Printing Co. I was the utility guy. I was good in the darkroom. I would burn plates. If there was a book to shoot I would shoot the whole book. I was versatile, that's why they liked me." Although he also pulled green chain at a lumber mill and worked as a clerk at Northtown Books, it was the print shop job that taught him skills he would use in his life as an artist. He liked his boss, Jerry Carter, and he liked the work, but he didn't see it as a career he wanted to pursue. He had other fish to fry. "I worked there five different times. Jerry said one time, `I fired you three times and you quit twice.' I said, `No, no, I quit three times and you fired me twice.' He knew that I couldn't stand to work at a job for very long. I always had to go make art.

Above right, the 1974 Comet Kohoutek poser that was his first surpise commercial success. Right, one of the posters Wesa did for a Northcoast Environmental Center seminar in 1973.

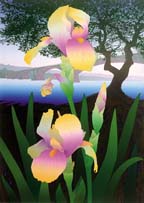

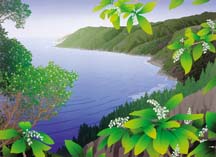

"It started in junior college. I made a pot and it sold like that," he said, snapping his fingers for emphasis. "I just loved that. It was really cool making art. You get to meet people. It takes you places. You get to know what people think. It's all part of the commerce of the idea. "That's why I like prints. They're like currency. You have this group affirmation. It was exciting when I would see my prints all around." Since his job at the printing company gave him access to a darkroom, he had a place to make stencils for silk screening. Friends began asking him to design and print posters for various occasions. He did work for the fledgling Northcoast Environmental Center and for other environmental organizations. In 1971 he and Wesley Chesbro, now the North Coast's state senator, had collaborated on a handbill/poster for something called Arcata Free University. When Chesbro ran for his first office, the Arcata City Council in 1974, Wesa designed and printed his posters. Another job came from his friends from HSU's film department, David Phillips and Rick Brazeau, who were opening the Arcata Theater. Poet John Ross commissioned a poster for a reading at the Jambalaya. Wesa knew that people liked his work because the posters placed in business windows would disappear. He saw it as a compliment when people would steal them to decorate their apartments and dorm rooms. A piece he made in the winter of 1973 proved to be a turning point. There was a buzz in the media about the coming of the comet, Kohoutek. "I thought, `I know what, I'll make a Comet Kohoutek poster, but not for some organization, just for me.' I went over to Jambalaya and sold a whole bunch of th em for six or eight bucks. All of a sudden I had $500 in my pocket. I made money doing what I'd been doing for other people for free. I thought, `Wow, I could do more of this.'" em for six or eight bucks. All of a sudden I had $500 in my pocket. I made money doing what I'd been doing for other people for free. I thought, `Wow, I could do more of this.'" To hone his skills and develop more discipline, Wesa entered the graduate program at HSU. He completed a masters in printmaking in 1976. "Then I had to break out of that period and discover myself again." "Consider the Sparrow" 1988, inspired by Luke 12:24. In his search for the hidden element that would make his art connect with the public, he found a niche. Once again he figured out what images people wanted to hang on their walls. His most popular pieces were landscapes, florals or a combination: Classic Wesa prints show a peaceful vista with flowers in the foreground. Wesa says the vistas he creates in his prints don't exactly reflect the real world. "I find the world really chaotic. It seldom presents itself in a way that I find pleasing." Instead his idyllic landscapes are "distilled from real places." People like his prints because Wesa offers a near perfect world, one where peace and harmony reign. "But I don't want to go to this other place -- nostalgia. Nostalgia is like pandering. It's like, you go to this place in the past to escape the chaos; there's a band playing, and it's so sweet. "Nostalgia is dead. What we really need to realize is that the good old days are right now, today. These are the good old days. Let's live them right now. Let's keep one foot in the future and not be going to the past." Wesa resists further inquiry into the deeper meaning of his work, particularly when it comes to his choice of subject matter. "It might seem like a paradox and a contradiction, but I claim that the subject isn't that important. It's how it's arranged, the feeling you get from the composition, the color, the contrast. That's what's more important. The subject is secondary. The subject serves my desire to get into the chiaroscuro, the dark and the light." The week before the exhibition opens Wesa's focus is on his retrospective. He's cutting mattes, framing the pieces himself, making sure each print looks just right. And when he's all done, when the show is hung, he knows what he has to do next. He has been commissioned to do an edition of prints commemorating the centennial of Crater Lake National Park. "Irises II" 1980, is one of Wesa's

most widely circulated works. The subject matter seems like a natural for Wesa. His work shows a certain clarity of vision, and the deep blues of the lake are easy to imagine in his style. Conceding that the assignment fits his approach perfectly, he says he actually resisted the commission. | What is serigraphy? THE WORD'S ROOTS ARE FROM THE LATIN sericum, silk, and the Greek graphein, to write or draw. It's an old process but a relatively new word, one coined in 1938 by an art critic, Carl Zigrossa. He made it up to describe an advanced form of silkscreen printing pioneered by a group of New York artists who worked in the Federal Art Project as part of President Roosevelt's New Deal. The process was an update on stencil printing, an ancient art technique that is found in Paleolithic cave paintings, in Egyptian tombs and in Greek mosaics. The Chinese used stencils during the period of the six dynasties of China (221-618 A.D.) to mass-produce images of Buddha. Legend has it Marco Polo brought examples of the silk stencil back to Europe. Basically serigraphy is a highly refined stencil process used to produce a multicolor screen print. The artist creates a series of stencils on screens made of silk, nylon of some other semi-porous fabric stretched on a frame. Paint is forced through the screen onto paper in a thin layer with a squeegee. The image is built layer-by-layer, stencil-by-stencil. A skilled serigrapher like Wesa uses carefully applied mixes of colors on dozens of layers to create handcrafted small editions. Wesa emphasizes that every single print is unique. And he supplies a legal certificate with each piece to that effect. "It's because people do offset prints, nice four-color offset prints. They sign them and number them, and they pass them off as wonderful `original' prints," he explains. "I'm like John Henry, the steel-driving man. He laid the rails with his hammer. That's me, I do it all by hand. It seems idiotic when there's a machine that could do it. Right? Except that you'll never get to know John Henry and all those things that he has to tell you about the birds in the air if you have a machine to do it all for you." | "They had to talk me into it. There are other things I want to do. It's too obvious. I'm not going to grow during the

period of time I'll spend doing the piece." How did he get the commission? Someone who knows his work asked him to take the job. "I have to say this, even though I know it brands me. How did I get the job? Because I'm good. My vision is agreeable and down to earth. Tha t's all." t's all."

Left, "King Range National Conservancy Area" 1995, used for the 25th Anniversary poster. Right, Fernbridge and Irises" 1987, used for a poster benefiting the Humboldt County Library.

Because of his "down to earth" vision, Wesa's prints show up on the walls of people who are not your typical art collectors. "There are people (coming to the opening) who told me they've never been to the Morris Graves before, people who aren't necessarily part of the art world," he says with a touch of pride. "I feel really blessed that I have people like that who like my work." After a moment's thought he adds, "I want my work to be accessible." He pauses again and a worried look comes over him. "I think sometimes I'm criticized by other artists for that, for being too accessible." Talk turns again to art school and bad habits artists learn there: like creating work that pleases other artists instead of the public. "You have to decide what you're going to do, what's important to you, where your treasure is. My treasure is all these people who like my work. It's not other artists." What does the retrospective say about him? He repeats the question before answering. "It shows persistence. I'm persistent. I don't really think of myself as particularly smart or brilliant. I'm a good technician and I just keep on keeping on. I often think of myself as a primitive artist." The thought occurred to him recently when he was reading something by Herman Melville. The author compared a scrimshaw artist and a South Seas islander who carves on a stone or a board with "the greatest primitive of all," the 15th century engraver Albrecht Durer. "When I read that I thought of myself, not that I'm like Durer, but there's this thing. You stand naked before God and say, `Pardon me, but this is my humble offering. That's all it is, just my humble offering. Please accept it.' That's me. I'm just standing here with my offering." Paints on a worktable in Wesa's McKinleyville studio. Posters for his retrospective exhibition are spread on the table. | the 3-D effect  ON THE BOOKSHELF IN WESA'S STUDIO THERE'S A STACK OF PHOTOS -- vacation pictures and portraits mounted with twin images on a piece of cardboard.

Wesa shot them with his 3-D "stereoscopic" camera. Beside them there's a stereoscope, a wooden viewer with lenses that holds the double photo so you can see the 3-D effect. Wesa points to a stereoscopic projector he just acquired explaining, "You put on special glasses and it's like the slides are coming out into the room."

John Wesa and his 3-D "steroescopic" camera.

Last Saturday night at the Morris Graves opening Wesa was dressed for the occasion like Tom Wolfe in a white suit with a bright tie. He stood inside the door of the Thonson Gallery greeting visitors. A friend brought him a copy of the retrospective catalogue to sign and, after making an inscription, he flipped to the back to show her a double photo. There are side-by-side images of Wesa's self-portrait -- the photo at the beginning of this story where he's holding a squeegee while standing before drying prints, posters for the exhibition. Wesa pulled a gadget from his shirt, a pocket version of a stereoscope. His wife, Rita, joked that it's the kind of thing most people don't normally carry with them. The visitor gazed through the lenses at the two photos in the catalogue for a moment, then exclaimed, "Yes, I see it now. It's three-dimensional!" On the other side of the gallery, someone pointed to a detail in one of Wesa's prints, remarking, "It's like the grass is coming right out of the picture." |

IN THE NEWS | ARTS! ARCATA | CALENDAR Comments? E-mail the Journal: [email protected]

© Copyright 2002, North Coast Journal, Inc. |  t's all."

t's all."

ter and a flavor in the way I do things that resonates with people. People get a peaceful, calm feeling, and I think that's antithetical to a lot of things that are out there, antithetic to what many people think art should be.

ter and a flavor in the way I do things that resonates with people. People get a peaceful, calm feeling, and I think that's antithetical to a lot of things that are out there, antithetic to what many people think art should be.

em for six or eight bucks. All of a sudden I had $500 in my pocket. I made money doing what I'd been doing for other people for free. I thought, `Wow, I could do more of this.'"

em for six or eight bucks. All of a sudden I had $500 in my pocket. I made money doing what I'd been doing for other people for free. I thought, `Wow, I could do more of this.'"