|

IN

THE NEWS | INTERVIEW | CALENDAR

by KEITH EASTHOUSE

It didn't take Jean Pfaelzer

[in photo below right] long to notice something odd about the class she

was teaching at Humboldt State University: no Asian students.

There were significant numbers

of Native Americans in the Humboldt student body back then, in

the late 1970s. There were also noticeable numbers of other minorities,

particularly Hispanics. But, campus-wide, Asians were few and

far between.

Puzzled, she made inquiries

and soon learned that HSU had a bad reputation among Chinese

and Japanese students in particular. It wasn't that the university

didn't want them. It was that the students didn't want to come

here.

The

reason for Humboldt's unpopularity, Pfaelzer eventually concluded,

had to do with something that took place over a 24-hour period

118 years ago -- the infamous expulsion of Eureka's entire Chinese

population, which at the time numbered about 300 men and 20 women. The

reason for Humboldt's unpopularity, Pfaelzer eventually concluded,

had to do with something that took place over a 24-hour period

118 years ago -- the infamous expulsion of Eureka's entire Chinese

population, which at the time numbered about 300 men and 20 women.

That event, which unfolded on

Feb. 5 and 6, 1885, was followed by a second, lesser-known banishment

of 23 Chinese cannery workers brought in to work on the lower

Eel River in 1906. Arriving in mid-September, they were shipped

out in early October after loggers objected to their presence.

It was not until the 1950s that the Chinese returned to Humboldt

Bay, when Ben Chin arrived and got into the restaurant business.

Chin's Cafe, next to Pierson's, is still a going concern.

Pfaelzer said that while most

Asians don't know the details of this history, they do know the

general outlines. "There's a very strong sense of history

and of stories passed down. This is clearly if unspecifically

known."

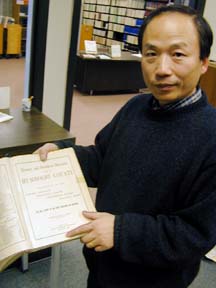

To this day, there are relatively

few Asians in Humboldt County. Ray Wang, director of HSU's Department

of World Languages and Culture, [in

photo, below left] was shocked

when he came here seven years ago. One of the first things he

did was open the phone book to look at familiar Chinese last

names, including his own. "There are 100 million [Wangs]

in China and here I found there were none. I couldn't believe

it."

Like

Pfaelzer before him, Wang sought an explanation and soon learned

about the events of 1885 and 1906. Like

Pfaelzer before him, Wang sought an explanation and soon learned

about the events of 1885 and 1906.

Many living in Humboldt today

know nothing about this dark chapter of local history; those

who do tend to view it at a distance, as if it has no connection

with the present. But the past treatment of the Chinese lives

on today in the form of a population that does not contain nearly

as many Asians as it might have.

"We would have a Chinatown

in Eureka," said Wang, adding that in the 1880s Eureka's

Chinatown was not too much smaller than San Francisco's.

It's worth noting that no Chinese

were killed in the two expulsions. It's also clear that the white

population took pride in what it had done. In 1886, the one-year

anniversary of the expulsion was celebrated in Eureka; the festivities

triggered additional expulsions of the comparatively small Chinese

populations of Arcata, Trinidad, Fortuna, Rohnerville and Ferndale.

As a result, in the early 1890s, the front page of a local history

and business directory was able to proudly declare, in boldface

type, that Humboldt was "the only county in the state containing

no Chinamen."

"I wouldn't go as far as

[calling it] genocide," Wang said. "But ethnic cleansing

is accurate. People were purged."

A

public airing

On March 11, the matter will

get the biggest public airing in memory when a symposium sponsored

by KEET-TV 13, HSU and the Humboldt County Historical Society

will be held at the university. The featured speaker is Pfaelzer,

who's working on a book that promises to be the definitive history.

The working title, The Driven Out, is also the title of

the meeting. The book's scheduled release date is the summer

of 2004.

Pfaelzer, 58, taught at Humboldt

for only a year -- it was her first teaching gig. But she never

forgot what she learned there. "It's a story that's always

haunted me. It was always going to be the next book," she

said in a telephone interview from her East Coast home last week.

A historian of the American

labor movement of the late 19th century, Pfaelzer, the author

of four works, finally turned her attention to the Chinese expulsion

about three years ago. She is currently on leave from the University

of Delaware, where she teaches. The university has provided her

with a grant to fund the book project. So has the Library of

Congress. Random House, which will publish the book, has given

her an advance.

Pfaelzer even has a writer's

lair here in Humboldt for reflection and inspiration, a cottage

near Big Lagoon that has long served as a vacation retreat for

her and her family. "My heart's in the county. Now that

I'm doing a book, it seems I'm out there all the time,"

she said.

She began her research with

a single, seemingly simple goal: to tell the tale of the Eureka

expulsion. After a few days at the Bancroft Library at the University

of California, Berkeley, however, she realized she was onto a

bigger story: Chinese expulsions happened not just in Humboldt,

but elsewhere in Northern California too, in places like Petaluma,

Shasta County and Truckee, where Chinese were killed. The ethnic

cleansing, it turned out, was widespread. "It wasn't just

a single episode," Pfaelzer said.

Pfaelzer estimated that several

thousand Chinese were expelled from 40 communities in Northern

California in 1885 and 1886. A burst of anti-Chinese activity

also occurred outside the state in the same general time period.

There was an anti-Chinese riot in the Seattle-Tacoma area and

an attempt to purge the population there; a number of communities

in Oregon drove out their Chinese residents; and more than 20

Chinese were rounded up and killed in Rock Springs, Wyo., a coal

mining area.

The

tenor of the times

While Pfaelzer said she "stays

up at night asking myself how this incredible racism spread,"

she actually had a pretty good explanation: racism was the

tenor of the times.

While the Civil War abolished

slavery, attempts after the conflict to bring political equality

to former slaves were quickly defeated. "Afro-Americans

couldn't testify, they couldn't vote, they couldn't go to school,

they couldn't own land," Pfaelzer said. Jim Crow laws migrated

across the county as southern Democrats came west and rose to

positions of political power. "They brought a version of

the black codes with them," particularly in California,

that were applied to the Chinese, Pfalezer said.

Some of the laws that were passed

were downright petty. In San Francisco, for example, Chinese

men were not allowed to arrange their hair in braids or pigtails,

a common custom at the time, or to walk around in wooden shoes,

which were deemed too noisy. More seriously, the state legislature

passed a law requiring Chinese miners to acquire a foreign miner's

license, which forced most Chinese workers into other jobs as

acquiring such licenses was not easy. On the federal level, the

Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 barred Chinese workers from entering

the country and set off a wave of resentment against Chinese

immigrants that was fueled by a blatantly anti-Chinese press.

While all that was going on,

the U.S. government was warring with Native Americans and putting

tribal people on reservations after defeating them on the battlefield.

What did that have to do with the Chinese? "The idea that

you can have an enforced mass migration of people was not unthinkable,"

Pfaelzer explained. "It was being done. It was available

at that time."

Against this backdrop was the

simple fact that the Chinese were different.

"There was an immense lack

of understanding of this group of people," Wang said.

"They didn't speak English. They didn't go to the same

churches. They didn't mingle. They dressed weird. They were deemed

as dirty, as a pagan population. They were easy targets."

Pfaelzer cited additional factors.

An 1875 law that made it illegal to bring Chinese women into

the country made it seem that Chinese people were not family-oriented.

Because Chinese men were comparatively small and often sported

pigtails, they were seen as effeminate -- a perception reflected

in political cartoons that depicted Chinese men in homoerotic

positions. Finally, unlike many whites, Chinese workers were

skilled and efficient, and willing to work for lower wages. It

was the belief that the Chinese posed an economic threat that,

perhaps more than anything else, explains the hostility that

was unleashed against them in the mid-1880s.

A

tragic shooting

It started in Eureka with a

random bullet.

David Kendall, 56, a member

of the City Council for three years, had just finished supper.

He was crossing a street in the vicinity of Chinatown, a one-square-block

area stretching from E and F streets between Fourth and Fifth

streets. It was about 6 p.m. on what Pfaelzer called "a

nasty, foggy night." It was Friday, then as now a time of

excitement -- and potential trouble.

Unbeknownst to Kendall, he was

about to step into the history books. Two Chinese men, possibly

members of rival "tongs," or gangs, began shooting

from opposite sides of the street. Twelve bullets were fired

in all. One hit the foot of a 12-year-old boy. Another hit Kendall,

killing him.

Within 20 minutes an angry mob

had formed in the streets of Eureka, chanting "burn Chinatown,

burn Chinatown." People poured into a building that no longer

exists, Centennial Hall -- "a big old barracks of a town

hall" is how Pfaelzer described it -- on the edge of Chinatown.

Some 600 shocked and infuriated men jammed into the structure,

bent on revenge.

The sheriff, Tom Brown, stood

up and told the crowd, in Pfaelzer's words, that "I've arrested

a bunch of men, but I can't tell you who shot David Kendall."

Pfaelzer said there are a couple

of ways of reading what happened next. One is simply that "a

real lynch mentality" took over as the crowd interpreted

Brown's statement to mean that the guilty party or parties would

never be found. A different interpretation is that some in the

crowd had already concluded that it didn't matter who had killed

Kendall; what mattered was getting rid of the real problem --

the entire Chinese population. Under this scenario, Brown may

have been pressured to not name suspects.

"Maybe it was convenient

not to identify" the perpetrators, Pfaelzer speculated.

Spontaneous

or planned?

What is clear is that Brown's

statement was pivotal. The crowd "got revved up," as

Pfaelzer put it, and without any clear leader it was decided

that the Chinese should be removed from the city within 24 hours.

A committee of 15 was appointed

to enter Chinatown and inform the residents that they had to

go. The committee was composed not of wild-eyed fringe elements

but of pillars of the community -- men such as future city councilor

H.H. Buhne, owner of a large store that supplied hardware and

wholesale groceries; Francis Thompson, editor of the Humboldt

Standard; Frank McGowan, an attorney; and Dan Murphy, a colleague

of Kendall's on the council and owner of the Western Hotel.

What really made the expulsion

feasible was the presence of two steamships in Humboldt Bay:

the Humboldt and the Chester, both of which were

used to transport the Chinese to San Francisco. Pfaelzer

said that "because of bad weather the ships happened to

be in the bay at the same time." Wang raised the possibility

that the ships were there specifically to transport the Chinese

out of the area. "Obviously, something had been arranged,"

Wang said.

Wang might seem guilty of fuzzy

thinking -- after all, how could anyone have foreseen the Kendall

killing? On the other hand, the white population was unusually

edgy. Pfaelzer said there was violence in Chinatown in the weeks

leading up to the expulsion, mainly due to the arrival of some

Chinese gamblers from San Francisco. "The Chinatown in Eureka

was a very stable, settled part of the community," Pfaelzer

said. But with the coming of the gamblers, "suddenly there

is violence in Chinatown that hadn't been there before."

Did the unrest lead community

leaders to plan the expulsion prior to Kendall's murder? That

may be going too far, but Wang thinks it's probable that preparations

were in the works; all that was needed was an excuse. "Some

people with ulterior motives were waiting for a good moment to

kick the Chinese out." If Kendall had not been killed, "it

would have been something else. People were waiting for a spark

to kick up this fire."

1885 photo of Fourth and E streets in

Eureka looking east. Chinatown is on the right and the first

few buildings on the left. Eureka City Councilman David Kendall

was accidentally shot at this crossing.

A slice of Eureka's Chinatown in 1885.

The sign in the background advertises Washing and Ironing by

Tung Sing.

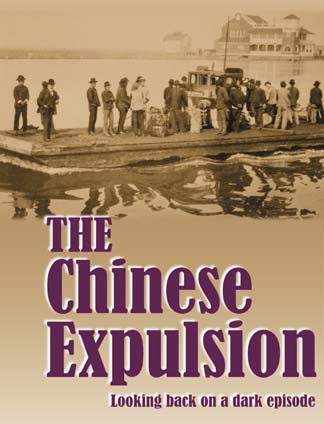

The 1906 expulsion of Chinese people

from Humboldt County.

A

narrow escape

Adding credence to the theory

that the expulsion was a less-than-spontaneous event is the fact

that what happened in Eureka was much larger and well organized

than the other expulsions in Northern California. It was also

remarkably free of violence.

Nonetheless, the possibility

of bloodshed was real.

A makeshift gallows was constructed

and a sign was attached to the wooden structure warning that

any Chinese still in town after 3 p.m. on Saturday would be hung.

A Chinese teenager, Charles Lum, made the mistake of stopping

in at the house of the Rev. Charles Huntington on his way to

the docks; he was being converted and wanted to say good-bye.

Outraged that a Chinese had entered a white house, a group of

vigilantes burst in, dragged Lum out, lifted him up to the gallows

and put a noose around his neck. Fortunately for Lum, Huntington

climbed the gallows and talked the crowd out of it.

Pfaelzer said she found the

plight of the 20 Chinese women particularly poignant. They must

have been hobbling as they were herded toward the ships due to

the Chinese custom of binding women's feet. They also must have

been distraught as many of them were prostitutes who had already

been kicked out of places like Sacramento and San Francisco.

"In returning to San Francisco, some of them were going

into double jeopardy," Pfaelzer said.

The banished Chinese arrived

in San Francisco the following Monday. A federal marshall tried

to get San Francisco police to detain eight to 10 men on the

grounds that they were suspects in the Kendall killing, but the

police said there wasn't enough evidence. They, along with all

the other Chinese on the two ships, were allowed to melt into

the city's Chinatown.

But the story wasn't over. In

a surprising move, 52 former residents of Eureka's Chinatown

obtained a white lawyer and sued the city of Eureka, claiming

that the city had robbed them of their property. The courts ended

up ruling against the Chinese, arguing that they had no standing

to sue because they had never been landowners; Eureka couldn't

have confiscated what the Chinese had never possessed.

Pfaelzer said the ruling "became

a flag that no one should sell property to the Chinese."

She also said that it was very much like what the courts did

to blacks in the Deep South, where former slaves had no legal

standing because they owned no land.

Other heroes

There were other whites in Humboldt

besides the Rev. Huntington who stood up for the Chinese. In

a well-known incident, Tom Bair confronted a group of Eureka

residents when they came to his Redwood Creek Ranch to take his

ranch hand, Charlie Moon. Standing in the road with a gun, Bair

reportedly told the group that they would have to take him first;

the group turned around and left.

Less well-known is what happened

in Orleans, a mining center in the late 19th century that harbored

a large concentration of Chinese. In a 1998 paper published in

the Humboldt Historian, the publication of the Humboldt

County Historical Society, Orleans resident Philip Sanders and

his daughter Laura wrote that only about half of the Chinese

population of Humboldt County had been expelled; the other half,

many of them miners, was never driven out.

Based primarily on the ledgers

of two Orleans mercantile stores, the father-daughter team found

that in the months following the 1885 expulsion, items that had

been popular with the Chinese -- such as rice, canned fish, incense

sticks and firecrackers -- continued to be purchased, but by

people with European names. Gradually, Chinese names began to

reappear in the ledgers, indicating that whites had been protecting

them.

The owner of one of the stores,

William Lord, was particularly sympathetic to the Chinese, even

going so far as to harbor them in his home during the expulsion.

Lord may not have been entirely altruistic. "The Chinese

economic role in town was so considerable that these guys would

have been screwed if the Chinese had been forced out," Philip

Sanders said in a telephone interview from his Orleans residence.

In their article, titled The Quiet Rebellion, Sanders

and his daughter estimated the Chinese population of Orleans

at 200 individuals or more throughout the 1890s -- a time when

officials in Eureka were claiming that the county was free of

Chinese.

It was a false claim, but as

Sanders explained Orleans had once been the seat of Klamath County,

which went belly up in 1874. "People didn't see Orleans

as part of the county," Sanders said.

Incomprehensible

hatred

As for Pfaelzer, she is clearly

in the process of attaining mastery over her material -- both

in terms of the Eureka expulsion and the expulsions that were

going on elsewhere in that troubled time. But, she said, she

will never be able to fully see the situation the way most whites

saw it. Even though she thinks it was misguided, she said she

can understand the belief that Chinese workers posed an economic

threat. What she can't get her mind around is the hatred.

"I am by disposition an

optimistic and happy person. The part of the story that will

never make sense to me as a human being is the contempt for other

people."

The KEET connection

If all goes as Seth Frankel

plans, he and historian Jean Pfaelzer will soon be collaborating

on a 30- to 60-minute documentary about the expulsion of Eureka's

Chinese population in the late 19th century.

Frankel, director of production

at KEET-TV, and Pfaelzer have already teamed up to produce four

two-and-a-half minute video spots, called "interstitials,"

on the expulsion that have been airing on KEET of late

In part, the purpose of these

is simply to drum up interest in a symposium on the expulsion

that is taking place at Humboldt State University on March 11.

The meeting, scheduled for 7 p.m. in Room 118 in Founders Hall,

will feature a talk by Pfaelzer, who is working on a book on

the expulsion entitled The Driven Out.

But the video spots, funded

by $12,500 in grants, are also intended to increase the chances

that additional financial support will be forthcoming to fund

the larger project.

The reason for the sudden attention

to Chinese issues is an upcoming three-part series by journalist

Bill Moyers on the Chinese experience in America. The series

will air on KEET from 9 to 10:30 p.m. March 25-27.

That the Frankel/Pfaelzer collaboration

happened at all is due to Matina Kilkenny of the Humboldt County

Historical Society. Kilkenny, who has known for some time about

Pfaelzer's book, put the two in touch after Frankel came to the

historical society to do research.

Frankel has done documentaries

before, notably a 60-minute piece in 2000 on local engineering

marvels (such as the Arcata marsh and the dam at Ruth Lake) that

got an Emmy nomination; and a historical series on the Rocky

Mountains in Colorado, where Frankel worked before coming here.

Why, aside from the fact that

funding may be available, is a film on the Chinese expulsion

worth doing?

"The majority of people

I've talked to don't even know this happened," Frankel explained.

"The point is not to rub peoples' noses in it and say `what

a terrible history we have here.' The point is to make people

aware so we don't let such things happen again."

-- reported by Keith Easthouse

IN

THE NEWS | INTERVIEW | CALENDAR

Comments? E-mail

the Journal

© Copyright 2003, North Coast Journal,

Inc.

|