|

Story by GEORGE RINGWALD

Photos by BOB DORAN

I AM HARDLY IN THE FRONT DOOR

WHEN THE TILE LADY, as I like to think of her, is showing me

a lamp she's taken from junk and made a piece of art.

"You can find these at

yard sales for $3 all the time, and at the Salvation Army,"

she says. "They're usually ugly. They're those goose-neck

lamps that students use a lot. And you can tile it; just make

sure that you put cement on the base so that it's weighted down

enough.

"It's so wonderful,"

she goes on, "because you can take all the junk that nobody

wants and people pass up because it's pink or it's yellow, and

that's not their color. And I tell people, `Don't care about

the surface, don't care about the color, look for the shape.'

![[tiled fruitbowl]](cover0207-fruit.jpg) "This was $6 at the recycling center,

this lamp. It was pink and nobody wanted a pink lamp, so I looked

at the shape of it, and I said, `Well, I'll tile it!' So I got

all these tiles, cut `em and glued `em on, and it's beautiful

now. Before, nobody wanted it for $6. Who wants a pink lamp?

Not too many people." "This was $6 at the recycling center,

this lamp. It was pink and nobody wanted a pink lamp, so I looked

at the shape of it, and I said, `Well, I'll tile it!' So I got

all these tiles, cut `em and glued `em on, and it's beautiful

now. Before, nobody wanted it for $6. Who wants a pink lamp?

Not too many people."

If she pauses for breath, I

don't notice it because she is already moving on to tell me:

"I try to teach people how to do things for very little

money, how to recycle, how to find the things that people say

at the end of the yard sale, `Oh, it's crap. You can have it

for a quarter.' Those are the ones we want. Those are our treasures.

"We look for shapes. We're

not looking for perfection or beauty, because we're going to

do that part. All we're looking for is a base. Or we're looking

for something that's broken, that we can smash up and make into

tiles to put over something else.

"Jeannie, who owns Wildberries

-- Jeannie and Phil -- came and took the workshop. She brought

a box of broken dishes that she had for 20 years because she

couldn't throw them away because they were part of the family.

She brought them and said, `Now I can finally do something with

them.'

"And she tiled them into

a tray, and the next workshop she tiled a clock. So you find

all those broken dishes when they fall to the ground, and you

go, `Oh, no, I loved that dish!' You don't do that anymore. You

go, `Oh, great! I couldn't break it myself, but now that it's

broken I can tile with it.'"

Laurel Skye -- for this is the

tile lady, whom I have to assume is the world record-holder for

non-stop monologist -- has a way of casually throwing out names,

sometimes admittedly not knowing their last names. (Jeannie is

Jeannie Fierce, to use her maiden name, and she and husband Phil

Ricord are the owners of Arcata's Wildberries Marketplace.)

Skye's home, in the 900-block

of 11th Street in Arcata, has a nondescript look from the outside

(although she has plans to give it a tiled cathedral entranceway),

but the inside is something else.

There are tiled floors, tiled

bathrooms, tiled bread-boxes, tiled napkin holders, bar stools

with tiled tops and even a bowl with artificial fruits, all tiled.

One is especially struck by

the number of crutches standing around the living room, some

picked up for a dollar at a yard sale, and now of course all

decoratively tiled.

![[decorated crutches]](cover0207-crutches.jpg) "I have to have a knee replacement,"

she explains, "and so I'm thinking: `Heal thyself! Throw

away your crutches! Decorate them. You don't need `em anymore.'

So I'm giving myself a subliminal message. And I'm doing crutches

everywhere. I think I'm going to be doing a show on crutches."

[ photo at left] "I have to have a knee replacement,"

she explains, "and so I'm thinking: `Heal thyself! Throw

away your crutches! Decorate them. You don't need `em anymore.'

So I'm giving myself a subliminal message. And I'm doing crutches

everywhere. I think I'm going to be doing a show on crutches."

[ photo at left]

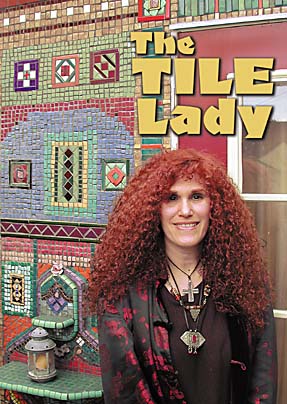

Skye has something of an other-world

look to her -- red hair that hangs in fizzes around her face,

dark brown eyes, a small nose ring and chopsticks in her hair

-- "decorative chopsticks," she is quick to add. On

this first day of our meeting, she is wearing a mélange

of what looks like black jump pants, no-nonsense black flats

and a voluminous Indonesian blouse-sweater.

"I'm a pretty eclectic

dresser," she concedes. ( I would never have guessed.)

The nose ring was acquired only

last year, at the age of 55.

"There is life after 50,"

she says with a light laugh.

When I manage to get a word

in edgewise, I ask her how she got started on tiling.

"Oh, I tiled my bathroom

in Berkeley about 20 years ago," she recalls. "And

then I stayed at a hotel in San Francisco, the Red Victorian.

And they said they had a room that needs tiling..."

Her

Humboldt County epiphany occurred some years back when she learned

that Los Bagels, in Arcata, was doing a contest for decorated

toasters. "So I tiled a toaster that said `Los Bagels' on

it, and I tiled a bagel into it on one side. I took it over and

didn't think anymore about it. Then I had some friends over and

in the morning I went over to Los Bagels to get some bagels for

everyone. And Dennis said, `Laurel, here's $25,' and he hands

me a check." She'd won the decorated toaster prize. [photo at right] Her

Humboldt County epiphany occurred some years back when she learned

that Los Bagels, in Arcata, was doing a contest for decorated

toasters. "So I tiled a toaster that said `Los Bagels' on

it, and I tiled a bagel into it on one side. I took it over and

didn't think anymore about it. Then I had some friends over and

in the morning I went over to Los Bagels to get some bagels for

everyone. And Dennis said, `Laurel, here's $25,' and he hands

me a check." She'd won the decorated toaster prize. [photo at right]

And I said, `Well, I'll be damned!'

And I looked at the toaster and I held the check, and in that

moment I thought: `Tiling? By me? I can do this for money?'"

And the students came running,

she observes. "People started coming over and saying. `I

want to make a toaster. Can you show me how?' More and more people

came, and then Dennis said, `How would you like to do 25 feet

of flower boxes in front of Los Bagels?' (Dennis Rael and Peter

Jermyn are the two original Los Bagels partners. Skye knew them

only by their first names.) So I did that, and got a little recognition.

"Oh, my God! I have such

great people, like Errol Previde, who won (the Journal's) best

guitarist of the year in Humboldt County last year; Jeannie,

and then the people who own Natural Selections, Pacific Flavors

and Brio, and the Ink People.... So many artists, and nurses,

therapists and teachers, and people who don't have an outlet

for that kind of creative activity because they're working in,

you know, 9-to-5 jobs.

"Mothers and daughters,

children. I just finished teaching at Fortuna High continuation

school for kids that are having some problems. This is the second

year they've had me back teaching mosaics there. And it's wonderful

working with those kids. They're creative, wonderful kids."

The next step in the tile lady's

still-budding career was to go public, in stock market jargon.

Student-customers kept asking where they could get the tiles,

and Skye met that desire by buying and purveying. She deals with

distributors from Vermont to North Carolina who cut stained glass

pieces of three-quarter inch and half-inch size.

![[tiled kitchen items]](cover0207-kitchen.jpg) A

corner of Laurel Skye's kitchen counter with tiled breadbox and

napkin holder. A

corner of Laurel Skye's kitchen counter with tiled breadbox and

napkin holder.

"They originally come from

China, Japan, Mexico and Italy," Skye says. "I get

them from wholesale distributors; I'm kind of like a middleman."

Skye is now also a supplier

of tiles to Pierson's in Eureka. Asked why they don't buy them

directly, Skye nods and says, "I don't know. Why don't they?

Because I think I have a connection to so many different places

that it's easy to just go through me. I have probably eight different

people that I deal with, and I bag the tiles, and they're labeled.

"I just pitched them an

idea," she goes on. "`What would you think about a

nice big sign all tiled that says `The Garden Center,' flowers

draping down?' Talked to the manager; his name is Morgan. He

said, `I love the idea.'"

Skye was in fact going back

at the time to restock Pierson's. "It will probably be the

fifth time that I've restocked them since I started with them

in July or August," she said.

Getting in edgewise again, I

ask: "And this is profitable?"

"No," she says, with

a laugh. "Financially, I don't think I could make money

to save my life. I'm probably making 50 cents, a dollar a bag

(of tiles). But what I'm doing is getting out there. I'm putting

my name out there. I'm going from being a hobby out of control

to being recognized professionally."

![[jars of colored tiles]](cover0207-jars.jpg) A rainbow of tiles for mosaic

addicts. A rainbow of tiles for mosaic

addicts.

Skye gives me a tour of the

house, starting with a look at a tiled bathroom. "Most people

do their countertops; I do everything." In the kitchen even

the door of the dishwasher is tiled.

"There's an altar,"

she says, pointing out one of several in the house. "I love

making altars," she explains. "I could make altars

for the rest of my life."

Indeed, given the altars and

the candles burning around the house, this is obviously as much

a sanctuary as a home or a workplace.

I note a kind of message, which

Skye translates as "Peace and equilibrium, balance, harmony.

Chinese. I got it from my Chinese calligraphy book.

"I tell people that this

is an addiction," she goes on. "Soon we're going to

be starting mosaic anonymous support groups, because none of

us can stop. And we're going to support each other; we're going

to go to each other's house and see what everybody else is doing.

This is becoming a vortex of energy in group thought right here."

On our way around the house,

I meet Skye's 15-year-old daughter, Kiah, who is a tiler as well

as a talented pianist, and I explain my presence by saying: `I'm

doing a story about your tile-addicted mother."

Kiah laughs and says: "I'm

the biggest addict of all!"

Skye points to another tiled

item, which she identifies as a bread box. "Three dollars.

And this is a napkin holder; yard sale, Salvation Army. This

is a clock that was a dollar."

Skye tells me: "I don't

usually sell my work. I give it away more than I sell it, but

I do sell at Garden Gate in Arcata."

We walk through a hall passageway,

the floor newly tiled and the grout sealed with silicone. On

one wall there is a slew of photos.

"This is also a place for

the Africans," Skye explains. "I have a lot of African

musicians who come to town to do concerts; they stay here at

this house. I don't know why." But then, actually without

a stop, she adds, "Maybe it's because I had a restaurant

in Berkeley for a couple of years, and I cooked African-Jamaican

foods, and I was connected there, so they know me and they feel

comfortable coming here -- musicians and dancers and drummers.

This is sort of a place where they can hang out."

![[mosaic worker]](cover0207-handsplate.jpg) ![[mosaic worker]](cover0207-handwork.jpg) ![[students in workshop]](cover0207-workshop.jpg)

Left/middle: mosaics being

pieced together.

Students learn the techniques of tiling at one of the workshops

Laurel Skye gives from her home studio.

Right, Brianna Kaufman and Peter Neufeld.

And if they need them when inspiration

hits, there are drums and guitars and the piano and a keyboard

in the house.

`Hey, Divina! Come on in,"

Skye says to another charming young woman who has suddenly materialized.

Skye introduces me to the aptly named Divina as her "good

friend and tiling buddy, who tiles up in Kneeland."

Skye then leads the way upstairs

(and I hadn't realized that there was an upstairs). Along the

way, we pass through a small jungle of plants at a bend in the

stairway, before we emerge into Skye's big bedroom.

"Here's my little tiled

altar, where I meditate in the morning. Before I come downstairs

and do anything, I sit here and meditate on just peace and being

in harmony and giving thanks for all that we have here. And the

sun comes right through this window and beams me up, Scotty."

There is a Buddha figure there,

but that doesn't mean that Skye considers herself a Buddhist.

"But there's so much of

the philosophy of Buddhism and Taoism that I embrace, and Christianity.

There's something in everything. I feel like this place is becoming

a church, that this is more than just a place of art, that it's

sacred."

By the bedside is some of her

reading -- Himalayan Passage, for example, and The

Dancing Wuli Dancers, which she informs me is a great book.

"Love it. Just fascinating,

the concept of time standing still. That time is no longer linear,

and that there's a time-space reality, because when you're doing

mosaic tiling, you move into that magical intersection where

time and timelessness intersect. And in that moment you forget

that you're hungry, you forget to pee, and it's that magical

place that everybody wants to be when they forget about time.

And mosaic tiling takes you there."

Prosaically, I find myself wondering

how many rooms are in this house, which incidentally, is "very

old," as Skye says. "It must be about 110 years old.

The back of the house is new, 10 years old, but this whole front

is at least a 100 years old. Like the late 1890s, that's what

the insurance people told me."

As to how many rooms (on a later

visit, I count at least eight, not counting bathrooms -- and

there are three of those), Skye says laughingly, "A bunch!

I don't know numbers. I only got to 4th grade. I don't even know

how to do addition. I bought a calculator finally, so I don't

screw up everybody's papers, because I really don't know math

at all.... I've been married 22 years to a doctor, who took care

of me. I don't know how to take care of myself.

"And yet I think that somehow,

when you run out of potatoes, God gives you rice."

![[Laurel Skye sitting in hallway of tiles]](cover0207-hall.jpg) Laurel Skye in the tiled hallway of her

Arcata home. Laurel Skye in the tiled hallway of her

Arcata home.

Blithe spirit that she is, Laurel

Skye has gone through her own little hell -- "quite a road,"

as she puts it. Three marriages -- one an architect, another

a money manager and the third a doctor. "All my husbands

were pretty successful."

She adds, "I had cancer

for a while, but I got that taken care of. One of my four children

died when I was in Chicago. He was hit by a truck, and that was

devastating."

Then there was the fire. It

happened in 1975, when she and her new husband were remodeling

a house she owned in Westhaven. Her husband had poured gasoline,

as a solvent, over the linoleum floor of the bathroom, and they

were both chiseling off the linoleum.

"So I'm chiseling away,

and the whole floor went Psshsssh! And blew up. What had happened

was that the gas fumes from the bathroom went into the kitchen,

caught on the pilot light of the water heater, and sent a trail

back. He (her husband) was right by the door; he hopped right

out. I'm wearing a flimsy little dress and huaraches, and I'm

standing there burning at the back of the room. And he says,

`Run!' How do you step into flames that are three feet high?

How do you walk through fire? The fire just came right up my

arm (she rolls back a sleeve to show the scars), and I'm like

in total shock.

"They flew me to the burn

unit down in Santa Clara, and I spent months down there in rehab."

She sold the house in Westhaven,

bought another house in Berkeley (staying by doctors down there).

Then her husband became a doctor and they went to Montreal for

four years.

"And you know, when my

husband left me after 22 years of marriage," Skye relates,

"I thought it was the end. I was in such depression. I had

my mom who had Alzheimer's, had a bunch of kids to take care

of and I went into major depression. And then I found tiling!

(Along with this many-roomed house in which to practice it.)

I've been like born again. I feel like I've been healed through

tiling. It's been such a joy."

She takes me outside to the

front of the house, to tell me about her next major project.

"This was all wisteria,"

she says, "and we just pulled it down."

In its place she plans to tile

the entranceway to the house.

"Something that gets you

from out here in this part of the world, into there," she

says. "So it's not like just stepping into something. There's

gonna be this passageway that shows you're going into something,

something's happening."

Knowing Laurel Skye, something

will be for sure.

She tells me: "This has

just been the most magical journey, and I've never been happier

in my life."

IN

THE NEWS | ELECTION 2002 | ARTS! ARCATA | CALENDAR

Comments? E-mail the Journal: ncjour@northcoast.com

© Copyright 2002, North Coast Journal,

Inc.

|