|

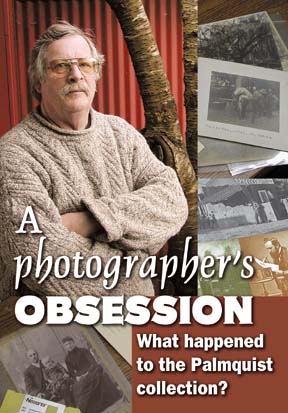

Story by BOB DORAN

PETER PALMQUIST IS A MAN obsessed

-- obsessed with learning all he can about the lives of photographers.

Over the course of the last three decades, he fed his obsession

and amassed a collection -- amazing in its size and uniqueness

-- of around 250,000 images with extensive notes to accompany

them.

Working out of his home in Arcata,

Palmquist built his private archive, one that rivals the collections

of public institutions. With 85,000 images by Humboldt County

photographers, it is a major resource for those with an interest

in local history.

But anyone interested in seeing

these slices of time will have to travel to do so, at least for

the immediate future. Palmquist sold all of his photos and notes

to Yale University last year. Most of the material has already

been shipped to New Haven, Conn., where it will be permanently

archived at the university's Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript

Library.

It

began with a handful of old photos. It was 1971 and Palmquist

was browsing in a McKinleyville antique store.

"The woman who ran the

place asked me what I was looking for, what I collected,"

he recalled. "I said, `Nothing.' She asked, `What do you

do?' and I said, `I'm a photographer.' She said, `Well, surely

you should collect photographs.'

"Before I left she gave

me a double fistful of carte de visites, photographs by

people I had never heard of, all from the Arcata-Eureka area,"

Palmquist said. "I was intrigued. I wanted to learn more

about them."

And that seed of curiosity about

the photographs and the photographers who shot them continued

to grow. While learning everything he could about Humboldt County's

pioneer photographers, Palmquist expanded his investigations.

By the end of the century the self-taught researcher had become

one of the foremost authorities in his field, an internationally

respected expert not just on Humboldt's photographers but about

the history of photography on the American frontier.

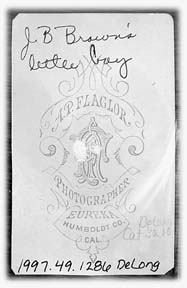

![[photo of Judge S.M. Buck]](cover0124-judgebuck.jpg) ![[photo of little boy]](cover0124-boy.jpg)

Carte de visites from the Humboldt County Historical Society photo

collection.At left, is Judge S. M. Buck, attorney. In the middle

is a young boy identified on the back side (right) as "J.B.

Brown's little boy,"

along with other collection information.

Palmquist's

rustic home is nestled among trees not far from his former place

of employment, Humboldt State University. From the outside, the

building behind the house doesn't look like a world-class library.

But inside floor-to-ceiling bookshelves are crammed with books

on photography and volume after volume of bound notes.

Over the course of last year

trucks from Yale made a regular pilgrimage to the Palmquist repository

and what remains today is mostly material connected to another

of his obsessions, the Women in Photography International Archive.

A few old photos in sleeves

sit on a worktable. Nearby is a thick book, Pioneer Photographers

of the Far West: A Biographical Dictionary, 1840-1865, "the

bible on the subject," he calls it. While it seems comprehensive,

it's just volume one of what Palmquist projects to be a five-volume

set.

Assembled with help from New

York-based editor/house painter Thomas Kailbourn, the 1,216-page

Pioneer Photographers tome was published last spring by

Stanford University Press. In November Palmquist and Kailbourn

received the Denver Public Library's Caroline Bancroft History

Prize, an award given annually to the authors of non-fiction

books about Western history.

As an expert on the lives of

photographers, Palmquist is used to putting together biographic

sketches. How does he describe himself?

"This is my 53rd year as

a photographer," he begins, and then pauses. "I'm local,"

he says after a moment of reflection.

Local, but not native. Born

in Oakland, Palmquist moved to a "side-hill shack"

on Boone's Creek in the hills above Ferndale when he was 8, his

father intent on a "back-to-the-land experience."

The fact that they had gravity-fed

water and no electricity didn't stop him from developing an interest

in photography.

"When I was about 12 I

started using my mother's box camera. There was nobody in the

community who did photography who could show me what to do, so

I just read about it. I went to Wing's Pharmacy in town and bought

chemicals mail order. By the time I was in high school, I was

really into it. I became the resident expert."

After graduating from Ferndale

High, he took his photo skills to the military. From 1954-59

he was stationed in Paris, home of the Supreme Headquarters Allied

Powers Europe, the military arm of NATO, a position that had

him photographing generals, presidents, movie stars, princes

and queens.

When his stint ended he was

offered a position in Brazil, but with a wife and a new baby

he thought it might not be a good idea. Instead he returned to

Ferndale and found work as a census taker.

After enrolling at Humboldt

State in 1960, courtesy of the GI Bill, he learned that the school's

photographer had quit.

"I took the job and kept

it for 23 years," he said as he quickly moves to a topic

more dear to his heart: research.

Just as he taught himself the

fundamentals of photography as a boy, Palmquist's entry into

the world of historical research was for the most part without

guidance. He has a college degree -- in ceramics, not history.

"I use methods that would

not be taught in universities, but they're effective. I find

stuff no one else can find because I don't know any better. When

you gather material endlessly, you gain a lot of insight,"

he said.

Palmquist pored over books looking

for clues, read every census record and "most of California's

newspapers and magazines through 1870 and some through the 1940s."

The Humboldt Room at HSU was

a starting point, but they were just beginning to gather historic

photos.

"In fact I was instrumental

in bringing the Ericson plates there," he said, referring

to a turn-of-the-century Arcata photographer who was the subject

of Palmquist's first book, Fine California Views: The

Photographs of A.W. Ericson.

"I had met the family and

helped them salvage some of the plates from an old barn,"

he explained.

He was already building a collection.

At a glance it might have seemed unfocused since it dealt with

such a broad subject: "the lives of photographers."

"I'm not passionate about

collecting photos of ships, not passionate about railroads. I

want to know who the photographer was," said Palmquist.

"And I've profited from staying in the field. I've been

the beneficiary of people who have died and given me their stuff.

I have research notes from colleagues and collectors, things

they left me. As you combine all this information a larger picture

comes into focus, one that benefits from the work of a lot of

people. I don't find every clue myself, but I accumulate them."

He shared his discoveries in

countless articles for scholarly publications and historical

society newsletters and put together more books. (His 63rd was

"on the press" when we spoke last month.) And he mounted

exhibitions.

In 1981, while doing research

for a major project, Palmquist met George Miles, newly hired

curator of the Western Americana collection at Yale's Beinecke

Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

"Peter was working on his

first big Carlton Watkins project, a book and a show that was

done in conjunction with the Amon Carter Museum," said Miles

in a call from Yale. "He came here to look at our things,

about which he knew much more than I did. So from the first I

began to learn from Peter."

When it comes to the history

of the West, the Beinecke is one of the major players. You want

to read the field notes from the Lewis and Clark expedition?

The originals are there, along with the original field maps.

"We're clearly one of the

best in the world when it comes to the history of the West up

until about World War I. Once you get past that we can't begin

to hold a candle to the sorts of collections that state universities

and state historical societies have built up for their particular

regions."

When Miles learned that Palmquist's

collection might be for sale he was interested. When he talked

with Peter and learned just how extensive it was, he became very

interested.

Why is it significant?

"It is probably the largest

private collection of 19th century Western photography ever built,"

said Miles. "I don't know of a larger one. There are people

out there who pursue this with a passion, and there are interesting

private collections that come up, But Peter's is on another order

of magnitude.

"There's more to it than

that," Miles continued. "It also is extraordinarily

thorough in certain areas. Peter was simply comprehensive in

collecting Northern California work, particularly Humboldt County,

from the earliest days of photography through to the mid-20th

century. Peter went out of his way to find the work of every

major photographer and to be able to document not just the history

of the region but the history of photography as it was practiced.

"I would also say that

part of what interested me about Peter's collection is not only

the original material he collected, but all the background research

that he did and compiled. The details he gathered are just staggering."

Each

photo in his collection offers a small glimpse of the past. While

Palmquist's intent has always been to look at history from a

photographer's point of view, other historians see different

things in his collection.

![[photo of Matina Kilkenny]](cover0124-matina.jpg) Among

them is Matina Kilkenny, [in

photo at left] research and collections

manager of the Humboldt County Historical Society. "There's

a story of the community that's part of each photograph, and

I think that it goes beyond who took the photograph. We value

them for what they can tell us about a time and a place,"

said Kilkenny at the society's headquarters in a Eureka Victorian

converted into offices and archives. Among

them is Matina Kilkenny, [in

photo at left] research and collections

manager of the Humboldt County Historical Society. "There's

a story of the community that's part of each photograph, and

I think that it goes beyond who took the photograph. We value

them for what they can tell us about a time and a place,"

said Kilkenny at the society's headquarters in a Eureka Victorian

converted into offices and archives.

Like many in the community,

Kilkenny sees the sale of the Palmquist collection as the loss

of an irreplaceable historical resource.

"The historical society

has a wonderful collection, more than 20,000 photos. It's nothing

compared to Peter's collection. But what I regret the most is

the loss of information, explicit information about individual

images," she said.

"Every picture we have

tells us something about our history. We need information to

interpret that history. We know more if we have the writing on

the back of the photo. It might be a note that came with the

photograph that says who the people were or the address of a

building. That's what left with the collection.

"A good example is the

picture you've seen on a poster recently with three postmen.

[below right] A woman had seen the photo and thought one of the

men might be a relation. She asked Peter if he had any information

about it. He knew who the people were; it was information that

had not been given out before. He emphasized how lucky she was

to get that information because that photo was being boxed up

the next day [for shipment to Yale]. I have to say that made

me mad."

![[poster of postmen]](cover0124-postmen.jpg) Palmquist

is well aware of the fact that there are many in the community

who were dismayed when they learned he had sold his collection

to a university back east. Palmquist

is well aware of the fact that there are many in the community

who were dismayed when they learned he had sold his collection

to a university back east.

"I take it your story is

about how this stuff has escaped Humboldt County," he said

at one point in our interview. "And I'm regretful,"

he added.

"There are all sorts of

critics who feel that the collection should stay here. If it

were to remain here, who's going to have it? Let's say the Historical

Society got it. They have limited staff. They have no provisions

for maintaining a historical record for the stuff with their

system. They might not put all the Ericson photographs together

because they sort by subject matter. Suddenly they're confronted

with putting all the trains in this pile and the Indians in that

pile. That would destroy what I've done."

Kilkenny points out that it

was Palmquist who devised the historical society's catalogue

system. Was there ever a chance that the collection could have

gone to the historical society?

"He never gave us any impression

that he was interested in donating one photograph to this collection,

much less 85,000. He's never donated a picture to us that I can

think of.

"Peter is an information

broker. It's that simple," Kilkenny continued. "And

I don't think that people who gave photos to him and shared photos

with him thought that they were selling the information that

went with them; they didn't know it was going out of the area."

In his own defense Palmquist

emphasizes his reputation.

"Reputation is everything.

You can imagine that there are others like me in the world. Some

of them can't be trusted. Those who are in the system know who

can be trusted and who can't. People will give me things they

wouldn't give anyone else because they trust me. I can't say

I have no critics, but most of my critics are people who just

don't know the circumstances, who don't understand what I'm doing."

He dismisses the idea that any

local institution has the resources even to deal with the portion

of the collection on Humboldt photographers.

"There are 85,000 photographs

(in the Humboldt portion). Are they going to put them in archival

sleeves, in archival boxes, find shelving space for them, space

where the temperature and humidity are completely controlled?

"Finding the proper respectful

home was essential. It's not like these are all Humboldt pictures

or pictures of Nevada City or pictures of Hawaii. The point is,

if you divorce them from the intellectual effort, the information

I've gathered about all the relationships the photographers have

one to another, you don't have a core collection. If it was dispersed

it would be pointless. It would destroy it."

Did he consider selling to the

Bancroft at UC Berkeley, another library with an extensive collection

on Western history?

"How long would it take

them to deal with my collection? It wouldn't happen in my lifetime,"

Palmquist replied.

"Part of Peter's concern

was to try to find an institution that had the wherewithal to

manage the collection effectively," said Miles, Yale's Beinecke

curator. "I would respectfully say that there are only a

handful of institutions in the country with the resources to

house the collection, appropriately maintain it and handle readers'

needs over a period of time. I'm fortunate to work at one of

them."

While Miles would not say how

much Yale paid for Palmquist's collection, he emphasized that

the photographs could easily have been sold for two or three

times as much money if it had been broken up and sold over a

period of time.

"The point is, it wasn't

about the money; it was really about preserving the collection

for scholarship," said Miles. And he contends Yale is in

the forefront when it comes to studying the West.

"One of the constant issues

for those of us collecting Western history here at Yale is, `Why

are you taking that stuff east?' It's a question we hear over

and over again."

His response: The history of

the Far West is an important part of the history of America.

Yale has demonstrated its commitment to the field by producing

many leading scholars who go on to teach at colleges and universities

in Western states.

Palmquist said he chose the

Beinecke in part because it's "on the corridor for students

doing research."

"That's something that's

lacking here. I'm next to a university, but the students never

see this place. They don't realize that cutting edge stuff is

being done right in their back yard. No one here understands

it."

What

happens to the collection now that it's at Yale? Palmquist has

suggested that with digital technology it will soon be possible

for people in Humboldt County to view the collection online.

"We're making efforts in

the digital field to put our collections up on the Web where

they can be more accessible for students, scholars and interested

amateurs from around the world who can't ever get to Beinecke,"

said Miles.

"But," he added, "I

don't want to make rash promises." Because of the vastness

of the Palmquist archives and because of the broad range of collections

at Yale, it will be some time before the collection is digitized.

"The Beinecke Library runs

from papyrus right through to modern literary manuscripts and

is extraordinarily strong in many fields. The communities of

users around the world are all interested in how digital technology

will make their life easier.

"We're all trying to figure

out what works best and how to make it happen, but we do have

a commitment to broad access. We collect material so it can be

used, not to lock it up."

Despite the sale, Palmquist's

research hasn't stopped. He's still hard at work studying women

photographers, still gathering photos and filling files with

notes.

He rests easier now that his

life's work is secure "in one of the finest rare book libraries

in the world."

"The collection will live

there in perpetuity. The facility itself is like a cathedral

with translucent marble panels so you have this beautiful soft

light. It's almost a mystical experience to walk in," Palmquist

said.

The way he sees it, the photos

he gathered now have a secure place in history.

"I'm simply a curator.

These things pass through my hands, but they belong to society."

![[photo of book]](cover0124-book.jpg)

Some of the 63 books

edited or written

by Peter E. Palmquist

A Collector's Obsession: Photographs

Of Humboldt County, California From The Peter E. Palmquist Collection. 2001.

Pioneer Photographers Of The

Far West: A Biographical Dictionary, 1840-1865 Peter E. Palmquist and Thomas R. Kailbourn.

2001.

Giants in the Earth: The California

Redwoods by Peter Johnstone

editor, Peter E. Palmquist photo editor/photographer 2001.

Women Photographers: A Selection

Of Images From The Women In Photography International Archive,

1850-1997 Peter E. Palmquist

and Gia Musso. 1997.

Shadowcatchers: A Directory

of Women In California Photography two volumes 1990/1991.

Camera Fiends & Kodak

Girls: Selections By And About Women In Photography, two volumes edited by Peter E. Palmquist.

1989/1995.

Return To El Dorado: A Century

Of California Stereographs From The Collection Of Peter Palmquist. 1986.

The Photographers Of The Humboldt

Bay Region Peter E. Palmquist

with Lincoln Kilian. - 1985.

Carleton E. Watkins: Photographer

of the American West

1983.

With Nature's Children: Emma

B. Freeman, 1880-1928 Camera And Brush 1977.

Fine California Views: The

Photographs Of A. W. Ericson

1975.

|

![[photo of Arcata Plaza]](cover0124-plaza.jpg)

Other Photo Collections

With over 20,000 images, the

Humboldt County Historical Society (703 8th St., Eureka)

has the largest public collection of historic photographs remaining

in Humboldt County. For more information got to: http://www.humboldthistory.org/

- The Humboldt Room at HSU

holds 2,000 plus images. Infromation about the collection is

available online at: http://library.humboldt.edu/infoservices/humco.html

497 plates from the Ericson photograph collection have

been digitized and can be viewed online at: http://humboldt.octavo.com/humboldt/index.html

[Above is a photo of the Arcata Plaza, by A. W. Ericson,

courtesy of the Humboldt Room, HSU Library]

- The Humboldt Room at the Eureka

branch of the Humboldt County Library (1313 3rd St.) has

a few hundred photos including "Shades of Humboldt,"

a small archive of photos copied from family collections. The

Clarke Memorial Museum (3rd and E sts., Eureka) also has

a small photo collection.

- Chromogenics in Fortuna (1130 Main St.), a business

run by Greg and Penny Rumney, has what seems to be the largest

remaining private photo colection: over 50,000 images, most of

them from Humboldt. Call them at 725-1200.

- Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript

Library website is at:

http://www.library.yale.edu/beinecke/brblhome.htm

It includes a searchable database of around 21,000 scanned images

from the Beinecke's collections: http://highway49.library.yale.edu/photonegatives/

- Peter Palmquist's Women in

Photography International Archive is online at: http://www.sla.purdue.edu/WAAW/Palmquist/

|

IN THE NEWS | EDITORIAL | CALENDAR

© Copyright 2002, North Coast Journal,

Inc.

|

![[photo of book]](cover0124-book.jpg)

![[photo of book]](cover0124-book.jpg)