|

IN

THE NEWS | CALENDAR

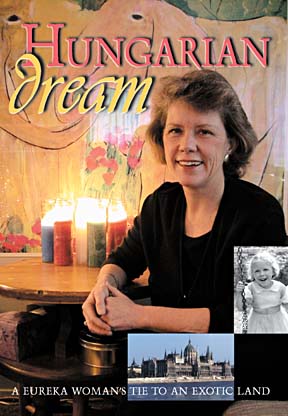

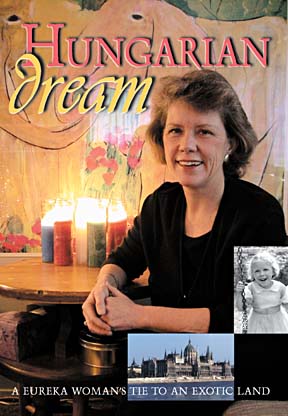

Louisa Rogers in her Old Town

Eureka home. Photo by Katie O'Neill.

Inset of Rogers on a swing in her backyard in Budapest, 1957,

and the Hungarian Parliament buildings today.

by LOUISA

ROGERS

[Recent scenes of the Danube

and the "Buda" side of the city.]

TO A 5-YEAR-OLD PEEKING OUT

THE WINDOWS of the U.S. Embassy, the tanks looked terrifying

as they rumbled down cobblestone streets. Gunfire echoed off

bullet-torn buildings; rubble lay in piles on the ground. The

5-year-old was myself, the place Budapest, the year 1956.

Forty-seven years later, on

a crisp November morning, I stood on a grassy square in front

of the Hungarian Parliament buildings, where one of the first

attempts by a small satellite nation to free itself from Soviet

rule took place. Huge black-and-white photographs depicting the

fighting of '56 were mounted on display. The sun shone brightly;

the Danube was just visible past the Parliament buildings. It

was hard to believe this lovely spot had been the location of

such violence.

I was back in Budapest to pursue

a dream: to apply the business skills I teach at home to this

post-Communist society. Thirteen years after gaining independence

from the USSR, Hungary is poised to join the European Union in

2004. My long-term goal was to train Hungarian businesspeople

in management skills and customer service. This week, I hoped

to make contacts and scope out possibilities.

[Left, two Hungarian

"freedom fighters" bearing arms in Budapest. The term

referred to Hungarians fighting against the Soviet takeover.

Time Magazine's January

1957 "Man of the Year" issue was dedicated to them.

Right, Budapest during the Soviet suppression of the Hungarian

revolt. Photos from the Hulton Archive.]

My

father, an American diplomat, was assigned to Budapest for four

years in the `50s. We lived there during turbulent times before,

during and after the Hungarian Revolution. It was an experience

that had a deep emotional impact on my parents and my family,

and ever since I have felt a connection with Hungary. It was

not my first time back; in the summer of 1986 my husband and

I bicycled across Europe and stayed in Budapest with my former

kindergarten teacher, a family friend. My

father, an American diplomat, was assigned to Budapest for four

years in the `50s. We lived there during turbulent times before,

during and after the Hungarian Revolution. It was an experience

that had a deep emotional impact on my parents and my family,

and ever since I have felt a connection with Hungary. It was

not my first time back; in the summer of 1986 my husband and

I bicycled across Europe and stayed in Budapest with my former

kindergarten teacher, a family friend.

[Left, Louisa Rogers

and her diplomat father on board an ocean liner from New York

to Le Havre, France, in 1953. State Department employees traveled

by ship which was cheaper than flying until the mid-'60s.

From there the family drove across Europe in their station wagon,

sent on the same ship, to Hungary.]

Before leaving Eureka for my

latest trip, I surfed the Web and found the sites for the American,

Canadian and British chambers of commerce; two English-language

newspapers in Budapest; and several business organizations. I

e-mailed the contacts, introducing myself, and heard back from

a few of them not as many as I had hoped. I was going to have

to invest more sweat equity than a simple e-mail to impress them.

EMBASSY NOW A FORTRESS

My old friend Bill, with whom

I would stay, picked me up at the airport. He is the site security

manager at the U.S. Embassy. In the taxi, he explained how, since

9/11, the U.S. government has been "dumping concrete"

all over its embassies. Indeed, when he showed me the building,

it looked like a fortress surrounded by a moat of concrete. Construction

consumed the entire block and apparently annoyed the neighbors.

Hungarians who want a visa to the United States have to wait

under open skies across the street until they hear their name

bellowed through a PA system. Then they navigate a succession

of outer checkpoints before entering the building.

Inside, Bill waited while I

showed the Marine on duty my passport. I peered around, remembering

fleeting images from the week I had lived in this building as

a child. The families of U.S. diplomats decamped to the

embassy for several days during the first stage of fighting.

To the 30-odd kids, it was a party. We got to sleep on mattresses

in our daddies' offices, eat in the cafeteria and have a Halloween

party. It was no picnic for the adults, however. There was only

one hot plate to cook on. And a week later, when the fighting

intensified, we were evacuated to Vienna. In the middle of a

snowstorm, visibility near zero, my father led a convoy to the

border where we were stopped by the Russian military and forbidden

to cross. (My father only turned around after a Russian soldier

pointed a rifle at him.) Local townspeople put us up in a schoolhouse,

where we children acted out the events we had witnessed that

day; one boy played the role of border guard while the rest of

us lined up to cross. The story of a group of American

kids playing a pretend game while in the midst of fleeing Hungary

made headlines in the United States. The next day, the Russians

allowed us to leave the country.

Today, the threat of communism

seems a distant ghost, and many might look back on it as absurdly

exaggerated. But it was very real the two superpowers, after

all, came to the brink of a nuclear exchange during the Cuban

Missile Crisis in 1962. In Hungary in the mid-'50s, the Red Army

was literally just over the horizon; so when the October 1956

uprising broke out, the hard fact of the matter was that no Western

country, not even the United States, was in a position to rush

in and help. For a few days, amazingly, it looked like the revolution

would triumph. Then the Soviet tanks came, crushed the uprising

and installed a puppet regime. "The Hungarian Revolution

seized the world's awareness as no other event of that period

did," my father told me once. "Thousands of Hungarians

left and were taken in by Europeans and by the U.S."

As Bill and I walked around

the embassy, I remembered a vivid scene: Our noses pressed to

the window on a gray afternoon, my sisters and I gazed out at

a crowd of people in faded jackets and berets, standing in front

of the embassy and singing the Hungarian national anthem. Though

I was only 5, I was deeply stirred by their emotion. "They're

asking for our help," my father explained. My oldest sister

wrote this letter:

Dec. 5, 1956

Dear President Eisenhower,

I am Elinor Rogers, 8. My

father is a diplomat and we live in Budapest, Hungary, Europe.

On Oct. 31 a band of Hungarians gathered in front of the embassy

and began crying something. Daddy said we couldn't help because

our army was in America. Europe is our fellow country and you

should help her if she is in danger. Even if you came halfway

across the country and then lost, you would at least have glory.

I wish America wasn't so rich. I wish I could give some of America's

richness to Europe, so they would be even. Europe will never

be friends with America, if you don't help now. Please do. If

you don't, I'll never like you again.

Elinor

KEEPING

UP APPEARANCES KEEPING

UP APPEARANCES

On Sunday, the day after I arrived,

Bill and I visited his friend Katalin on the other side of the

Danube. Budapest is built around a river; Buda is the hilly,

mostly residential side; Pest is the commercial center. The city

looks and feels like a quieter, gentler Paris. "Europe's

best-kept secret," I read in a tourist brochure.

When we arrived at her home,

I was relieved that I had changed out of my Humboldt casuals

and dressed up, at least minimally; like most Europeans, Katalin

dressed elegantly even in casual moments. A bilingual woman with

an adult son living in New York, she owned a business leading

cultural and historical tours for Americans and other English

speakers in Budapest. She poured me Hungarian wi ne

in a long-stemmed glass and we sat in her living room, discussing

possible contacts. Bill had told me she had money worries, but

I would never have guessed. Her clothes and furniture looked

much more upscale than mine. But I remembered from family stories

that Hungarians have a great deal of pride. ne

in a long-stemmed glass and we sat in her living room, discussing

possible contacts. Bill had told me she had money worries, but

I would never have guessed. Her clothes and furniture looked

much more upscale than mine. But I remembered from family stories

that Hungarians have a great deal of pride.

[Left, Rogers,

standing in front of the monument in Szent Entendre (Saint Andrews)

Square. Right, pedestrians in downtown Budapest view posters

of the events of 1956 .]

The next morning, at the Budapest

Breakfast Networking Organization, 12 of us met in the private

room of a restaurant, eating eggs and toast and Hungarian sausage.

The director, Paul, was a former executive from Manchester, England,

who had launched two networking groups in Budapest: this one

in English, another in Hungarian. One by one, we introduced ourselves.

Our group consisted of the director of an executive search firm,

the owner of a mystery shopper service, an attorney/mediator,

several marketing consultants, a magazine photographer, an owner

of an espresso cafe, and an owner of a chocolate and candy shop.

Besides the Hungarian members, there were several Brits, one

American and an Italian in the group.

This week it was Brendan's turn

to give a 10-minute presentation on his marketing business. After

his talk, the discussion veered into customer service, which

is lacking in Hungary. "I would market customer service

in the context of cultural change if I were you," said Brendan,

a Briton. "How do you encourage change in a people who have

been told what to do for more than 50 years, and robbed of any

initiative? There's a need for customer service, but the bigger

issue is cultural change."

"How to bring about change

without losing control," Paul said. "Many managers

are afraid of being exposed as unknowledgeable. Their autocratic

management style covers up this fear. There's a Hungarian saying:

`God made the earth in six days and rested on the seventh. On

the eighth day along came a Hungarian who corrected God's mistakes.'"

Peter, director of the executive

search firm, came up to me and suggested we refer clients to

each other. I didn't want to discourage possible business, but

a reality check seemed only fair. I told him I was willing, but

it was unlikely to happen often. It's not as though I regularly

run into people in Humboldt County who are relocating to Hungary.

Nadas, the attorney, offered

to help with contracts if I set up trainings in Hungary. I had

been advised to be very careful with contracts. Along with poor

customer service, there were widespread problems with business

ethics. I remembered what Ernie Nagy, my father's friend and

Embassy colleague, had said about the revolution: "What

set it apart from all others was its near perfect purity: no

looting and almost total unanimity of purpose." It sounded,

sadly, like times had changed.

SERVICE, ANYONE?

Every day, an early morning

constitutional. Bill and I would leave the apartment, head over

to the Margit Bridge, then walk the length of Margit Island,

which lies between the two halves of the city. We'd walk along

the gravel-jogging path, past the thermal baths, watching the

sunrise through the linden trees.

And every day, a meeting. On

Tuesday I had lunch at the Iguana, an American-owned Mexican

restaurant, with Shar, the president of NAWA, the North American

Women's Association, whom I had found on the Internet before

arriving. Shar brought along Sue, a Canadian from Ottawa married

to a "'56er," the phrase for Hungarians who lived through

the revolution. I explained my goal: to offer trainings in Budapest,

returning two or three times a year, not relocating.

Sue took a generous bite of

burrito. "I just don't get it," she said. "I don't

see how you can make it work from a distance."

"How will you do follow-up?"

Shar asked. "Hungary isn't like the States or Canada, where

the concept of customer service is wired into us. I don't think

you can offer customer service in two or three hours and expect

it to stick."

The problem does indeed run

deep. During my 1986 visit, I was sitting at a Budapest cafe

with a friend and waved at the waiter, trying to get his attention.

My companion laughed at me, explaining that, if anything, my

gesture would put the waiter off. Since communism tried to eliminate

the profit motive, the concept of service, that the customer

comes first and should be attended to, was alien. There was simply

no economic incentive to do so.

Clearly, that is is still a

problem today. All week I heard a litany of the terrible quality

of customer service. Even multinational corporations with record

sales had trouble maintaining high customer service in Hungary.

Consulting firms offered customer-service trainings, but they

didn't seem to have a lasting effect. I wondered how I could

use this problem to my business advantage.

That evening, Zsuzsa, Bill's

Hungarian language tutor, dropped by. Yet another well-dressed

woman, she was decked out in a wool suit, neck scarf, costume

jewelry and high heels. We sat on the couch talking away like

old friends. She told me she'd love to move to the United States

but didn't have connections. Several of her family members had

health problems, and she couldn't abandon her aging mother. I

could picture her in the States: one of those indefatigable immigrants,

willing to work hard, thrilled by the structural and psychological

freedoms the United States offers.

"Do you speak any Hungarian?"

Zsuzsa asked.

"Igen," I said, meaning

"yes." Then I broke into English: "I remember

four words: `yes,' `no,' and `watch out.'"

"When you come back, I

will give you a lesson."

Like many middle-aged Hungarian

women, Zsuzsa was divorced. She talked openly about her ex-husband's

infidelity, which is common in Hungary. She blamed it on communism.

Women were forced to go to work too early, in her opinion, before

they were ready. They worked for totalitarian bosses who exacted

sexual favors. Home didn't offer much of a positive alternative

alcoholism and domestic violence were also common. Hungary has

the highest rate of alcoholism in Central Europe, and until 10

years ago, the highest suicide rate in the world. Although it

has declined, it is still high.

TWIN CRISES

The next morning I left the

apartment early. It was still dark, but I felt no danger. I felt

elated on the streets of Budapest, walking in the lee of old

stone buildings, hearing the chug of trams, crossing the Danube

along one of several bridges. As I reached a major avenue, I

suddenly realized it was the street my father had written about:

Anton and I left the embassy

as dusk was falling, to be home before dark, and drove slowly

down Bajcsy-Zsilinszki ut (street), which was bristling with

tanks. We were the only civilian traffic. At the bridge, the

Russian and Hungarian army patrols checked our papers and permitted

us, as diplomats, to pass. Then we eased between two tanks. I

suppose it is easy to describe the face of the enemy they seem

usually to be called `glowering' or `threatening' and it is true

these soldiers certainly did not give any impression of camaraderie.

But who can describe another's inner feelings at such a time?

Some Russians defected during the revolution. Perhaps our `threatening

Mongol' was one. Did he think he was standing on a Nile bridge,

or in Berlin, instead of over the Danube? And the Hungarian soldier

what did he do the day before and the day after? How did he come

to find himself patrolling side by side with the hated enemy

that his countrymen, with a unity unknown in their entire history,

had just risen against? On the other hand, I suppose one has

to give his momentary impressions of the enemy, subjective though

these be. I never saw a pro-Soviet force during the revolution

man or tank which struck me as anything but hostile and threatening.

My

father's reference to the Nile was no accident. On an earlier

trip to Budapest, my former kindergarten teacher described her

run-in one night during the revolution with a Russian soldier

who asked her for a cigarette. As she gave him one, he gestured

toward the river and asked, "Suez?" Russian conscripts

had been told they were going to Egypt. Why? Because at the very

same time Hungarians were rising up, Israeli brigades, backed

by the English and the French, invaded the Suez Canal. The goal

was to thwart Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser's attempt

to nationalize the strategically vital transportation corridor,

but it backfired after the Soviet Union threatened to intervene

and after President Eisenhower condemned the attack. My

father's reference to the Nile was no accident. On an earlier

trip to Budapest, my former kindergarten teacher described her

run-in one night during the revolution with a Russian soldier

who asked her for a cigarette. As she gave him one, he gestured

toward the river and asked, "Suez?" Russian conscripts

had been told they were going to Egypt. Why? Because at the very

same time Hungarians were rising up, Israeli brigades, backed

by the English and the French, invaded the Suez Canal. The goal

was to thwart Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser's attempt

to nationalize the strategically vital transportation corridor,

but it backfired after the Soviet Union threatened to intervene

and after President Eisenhower condemned the attack.

[Above, Rogers on her bicycle in Budapest,

Aug. 1986. At left, the author, and her kindergarten teacher,

left, Thekla Liptay-Wagner.] [Above, Rogers on her bicycle in Budapest,

Aug. 1986. At left, the author, and her kindergarten teacher,

left, Thekla Liptay-Wagner.]

NETWORKING

Later, I hopped on the tram

to cross the river. The Soviets invested heavily in public transportation,

leaving Budapest with a fine tram and subway system whose tentacles

spread far. This afternoon I was meeting Willy Benko, the managing

director of Euronet, a company that makes cash-dispensing machines

in Europe, and the man known as "Hungary's motivational

speaker." I was pleased he was willing to meet me. In fact,

everyone seemed willing to meet me. Why? All right, I was American,

but "Eureka" is not exactly on the map. Perhaps the

fact that I was there for only a week? But if I were to arrive

in, say, Atlanta, and announce, "I'm here for a week,"

I couldn't imagine people necessarily opening doors.

We sat in the company conference

room, drinking coffee in china cups, with delicate ginger cookies

presented on a silver tray. Willy turned out to be another bilingual,

had lived in Texas and knew Dr. Phil. He was the speaker every

month at the "Budapest Power Lunch." He had also launched

Hungary's only Toastmasters club.

"What's your main topic

at the power lunch?" I asked.

"Personal responsibility.

You can't talk enough about that here. In Hungary, failure is

not an option. If mistakes happen, they are always someone else's

fault."

"I've worked with a lot

of companies in the states where the same thing is true,"

I said.

"Yeah, but it's a matter

of degree. If Hungary is going to succeed in the European Union,

we have to overcome the old mind-set. We've had 13 years of independence,

but we have a long way to go."

During the week, I decided to

attend the "Big Smoke Executive Cigar Club Networking Event,"

held at a local bar, sponsored by the Budapest Business Journal

and the Hungary Tobacco Institute. Evidently Hungary hadn't joined

the anti-smoking bandwagon yet. I wasn't thrilled by the thought

of an evening of cigars, but I dropped by the business journal's

office to sign up anything for the cause. The young male clerk

at the desk shook his head, saying, "I'm sorry, but this

event is for executives only."

"I am the executive

of my company," I said, filling every inch of my 5'1"

frame.

"Oh, I'm sorry," he

said, and signed me up.

At the bar, I arrived early,

and forced myself to go up to a man who turned out to be from

neighboring Slovakia. Networking is always a bit awkward in the

beginning, but it was easier in Hungary. From that moment on,

the conversations didn't stop. I met business owners, high-level

managers, and journalists, mostly men, a few women. By the end

of the evening my clothes had a smoky flavor, but didn't reek.

I didn't sample a cigar. Few people did.

A NEW REVOLUTION A NEW REVOLUTION

My networking produced some

tangible results: The Budapest Business Journal, published

by a guy from Philadelphia, will run my business column; I've

been invited to be a guest speaker at the power lunch; and the

Central European University, which acts as a broker to companies

requesting trainings, will recommend me when they have a request

for an English-speaking trainer.

It's a start. I would love to

fulfill my dream, and be invited back two or three times a year

all expenses paid, of course. But whether that transpires or

not, my week in Budapest was worth every moment. Nothing stirs

my sense of vitality more than taking action on a dream. I can't

really understand or empathize with the depth of change asked

of Hungarians in this time; I've never had to face the kind of

changes they face. But I respect the challenges in front of them,

and if I can be a part of their new revolution, I would consider

it a privilege.

Louisa Rogers is a Eureka-based

business trainer and coach who specializes in customer service,

management skills and communication

in the workplace.

IN

THE NEWS | CALENDAR

Comments?

© Copyright 2004, North Coast Journal,

Inc.

|

My

father, an American diplomat, was assigned to Budapest for four

years in the `50s. We lived there during turbulent times before,

during and after the Hungarian Revolution. It was an experience

that had a deep emotional impact on my parents and my family,

and ever since I have felt a connection with Hungary. It was

not my first time back; in the summer of 1986 my husband and

I bicycled across Europe and stayed in Budapest with my former

kindergarten teacher, a family friend.

My

father, an American diplomat, was assigned to Budapest for four

years in the `50s. We lived there during turbulent times before,

during and after the Hungarian Revolution. It was an experience

that had a deep emotional impact on my parents and my family,

and ever since I have felt a connection with Hungary. It was

not my first time back; in the summer of 1986 my husband and

I bicycled across Europe and stayed in Budapest with my former

kindergarten teacher, a family friend. KEEPING

UP APPEARANCES

KEEPING

UP APPEARANCES ne

in a long-stemmed glass and we sat in her living room, discussing

possible contacts. Bill had told me she had money worries, but

I would never have guessed. Her clothes and furniture looked

much more upscale than mine. But I remembered from family stories

that Hungarians have a great deal of pride.

ne

in a long-stemmed glass and we sat in her living room, discussing

possible contacts. Bill had told me she had money worries, but

I would never have guessed. Her clothes and furniture looked

much more upscale than mine. But I remembered from family stories

that Hungarians have a great deal of pride. My

father's reference to the Nile was no accident. On an earlier

trip to Budapest, my former kindergarten teacher described her

run-in one night during the revolution with a Russian soldier

who asked her for a cigarette. As she gave him one, he gestured

toward the river and asked, "Suez?" Russian conscripts

had been told they were going to Egypt. Why? Because at the very

same time Hungarians were rising up, Israeli brigades, backed

by the English and the French, invaded the Suez Canal. The goal

was to thwart Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser's attempt

to nationalize the strategically vital transportation corridor,

but it backfired after the Soviet Union threatened to intervene

and after President Eisenhower condemned the attack.

My

father's reference to the Nile was no accident. On an earlier

trip to Budapest, my former kindergarten teacher described her

run-in one night during the revolution with a Russian soldier

who asked her for a cigarette. As she gave him one, he gestured

toward the river and asked, "Suez?" Russian conscripts

had been told they were going to Egypt. Why? Because at the very

same time Hungarians were rising up, Israeli brigades, backed

by the English and the French, invaded the Suez Canal. The goal

was to thwart Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser's attempt

to nationalize the strategically vital transportation corridor,

but it backfired after the Soviet Union threatened to intervene

and after President Eisenhower condemned the attack. [Above, Rogers on her bicycle in Budapest,

Aug. 1986. At left, the author, and her kindergarten teacher,

left, Thekla Liptay-Wagner.]

[Above, Rogers on her bicycle in Budapest,

Aug. 1986. At left, the author, and her kindergarten teacher,

left, Thekla Liptay-Wagner.] A NEW REVOLUTION

A NEW REVOLUTION