Witness Marks

The Carson Block Building Restored

By Linda Stansberry [email protected] @lcstansberry[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

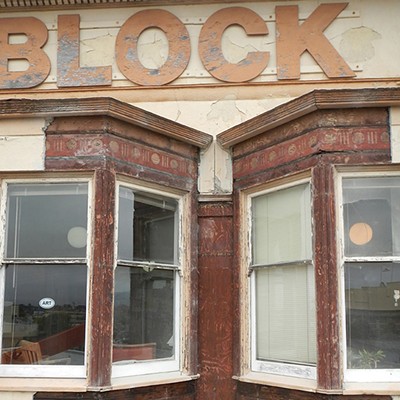

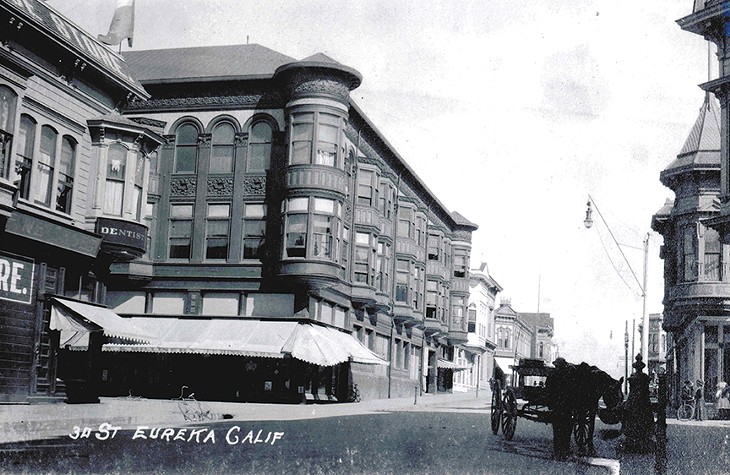

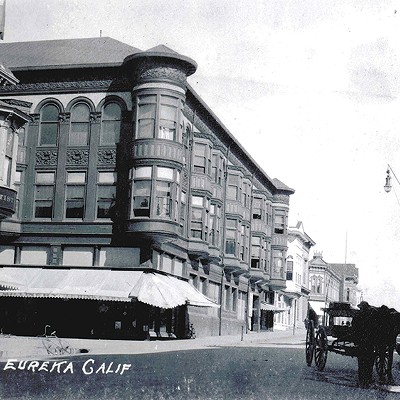

She was once the first, the finest and the fairest, but as the 20th century progressed and the Carson Block building became middle-aged, her owners decided the grand old madame had no right to show her wrinkles. They troweled a layer of stucco over her stately redwood boards. In 1958 they removed the turret that had thrust its proud chin into the intersection of Third and F streets since 1892, installing a buzzing neon sign instead. The once lavish Ingomar Theater, with its plush seats and intricately decorated domed ceiling, was gutted, truncated and relegated to a more utilitarian purpose: the storage of furniture. As with so many ladies of a certain age, the building's grandeur became obscured as time and ignorance pushed her out of the spotlight. But now, thanks to the painstaking efforts of a devoted fan base, Old Town's reigning diva has been rediscovered, painted a defiant dark red, and is ready for her close up.

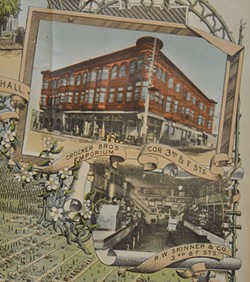

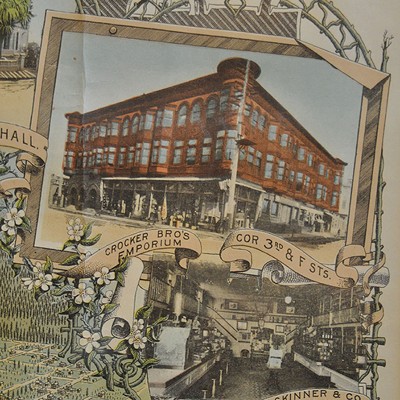

William Carson had a vision. It was just one in a string of visions that, in 1851, led the Canadian to the frontier town of Eureka, which, at the time, was a rough-hewn collection of small homes and saloons adjacent to a military post. Redwood stumps still dotted what is now First Street. Most homes were built in the Greek Revival style, flat-faced buildings with columned porches, harkening back to the New England villages from which many white settlers had come. Carson, arriving at the tail end of the region's gold rush, would go on to make his fortune in redwood timber. The Carson Mansion and the adjacent Pink Lady (built as a wedding present for his son) to many represented Carson's attempts to add sophistication to the scrappy seaside town. The 51,000-square-foot Carson Block building, with its opulent theater, bas-relief terra cotta panels, freizes, arches and high-windowed storefronts, built in the Romanesque Revival tradition, was meant to anchor the heart of Eureka's Old Town as a center of commerce and culture.

More than a century later, Carson's dream is being resurrected from its stucco tomb, although his legacy may be tarnished by the context of colonialism. While the lumber baron was one of the few white settlers on record to acknowledge Wiyot sovereignty over the land on which he built his empire — he "bought" the site for his lumber company from a Wiyot man in exchange for a sack of flour, an old musket and ammunition — his success on the rocky shore of Humboldt Bay, originally called Wigi by the Wiyot people, was built on a foundation of theft and genocide. If his affection for the play Ingomar the Barbarian, a turgid romance about a fair maiden surrendering to, and then civilizing, a "savage" barbarian chief, is any indication, Carson was a man philosophically aligned with Manifest Destiny and all its concurrent tragedies.

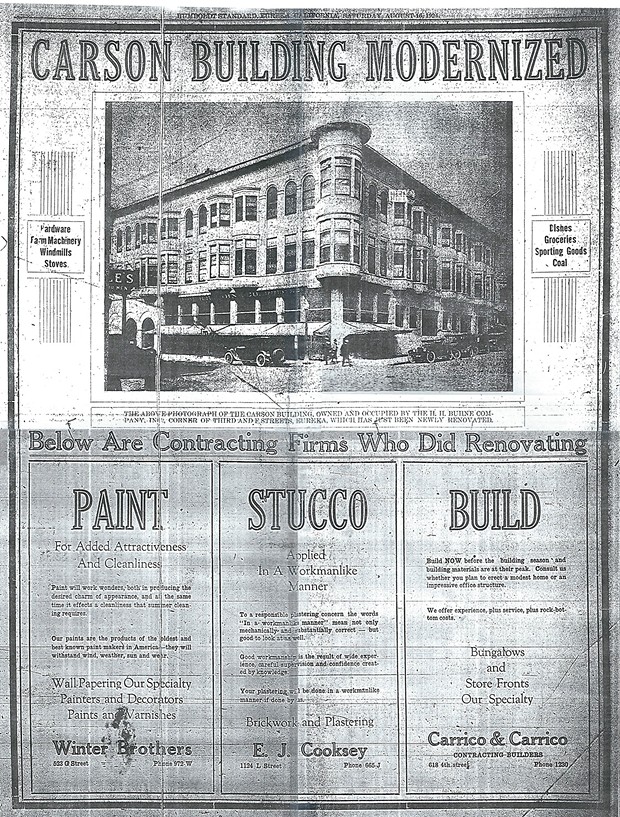

According to the Eureka Heritage Society (whose work was essential to this story), Carson's family maintained the commercial building faithfully until its sale in 1923. Carson could not have predicted the change in architectural taste that led to its deterioration, nor its eventual rescue from ignominy by a group dedicated to meeting the economic and social needs of Native Americans: the Northern California Indian Development Council.

"I've always thought he'd be rolling over in his grave since we bought the building," says Terry Coltra, NCIDC's executive director. Coltra said restoration of the building has been his goal since its purchase in 1986, but dips in the national economy and the added cost of a seismic retrofit — mandated by law after the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake — pushed this dream to a backburner. There it remained at a simmer until 2013, when the NCIDC pieced together funding through a variety of sources. The California Cultural and Historical Endowment granted $1.5 million to restore the façade and roof. The Arcata Economic Development Corporation, Headwaters Fund, Redwood Region Economic Development Commission and Humboldt Area Foundation all collaborated on an additional $1.5 million loan. Another $5 million came in through the New Market and Historic Tax Credit process. And the city of Eureka secured a $5.3 million community development block grant, which included a $1.5 million grant and a loan of $3.6 million, which the NCIDC will pay back over the next 50 years. The NCIDC has spent $11,500,000 to date on the project.

"I've been working on this for 10 years, kind of since the day I got here," says Kathie Hamilton Gentry, NCIDC's senior planner. "It's so beautiful to see it come to fruition."

Work began in earnest in December of 2014, and Coltra admits it has been time consuming on top of his regular responsibilities.

"Every other day there's another issue that needs to get resolved," he says. "This is taking on a lot for a small nonprofit. Some people would call me crazy, but if you don't have vision, you'll never get anything done."

Coltra was initially drawn to the building's inner beauty — specifically the theater, the restoration of which remains to be funded. Like the rest of the building, the Ingomar couldn't be restored until the seismic retrofit was finished. And because funding for the retrofit was tied into its historic preservation, the project drew together a group of experts ready to peer beneath the layers and reveal the building's outer beauty as well. The NCIDC had been working with an architect versed in historic preservation — Joe Monteadora, of San Francisco's John Sergio Fisher and Associates — for almost the entirety of its ownership. They also retained the services of Page & Turnbull, a firm that helped restore San Francisco's Ferry Building and other high-profile projects. John Lesak, an architect with Page & Turnbull, describes the Carson Block building as unique to his 25 years of experience in historic reconstruction.

"It's a great project, really wonderful," he says. "A lot of the stuff was there, it was just covered over. We did the investigative work of taking things away and finding stuff we could restore."

It is unknown why the previous owners installed stucco over the original design, although some posit that the redwood and terra cotta was too expensive to maintain. Funding from the California Cultural and Historical Endowment relied on returning the building to as close to its original form as possible. Although Page and Turnbull removed a small portion of stucco in its original analysis of the building, no one involved in the restoration could have anticipated all that lay beneath.

"It was like opening a big package at Christmas," says Bill Hole, a design and technical consultant for the project.

Every old building is a collection of scars, bumps and lines that testify to its history of use. Called "witness marks," they help direct reconstructionists how to proceed with repairs. Some are large, like the brick archways in Opera Alley that once gave entry to the Ingomar Theatre. Others are as small as a square nail. Much of the building's facade was deeply damaged by the stucco. The brick and redwood had been suffocated, damaged by water trapped against them. Many bricks had to be recast and replaced. The beautiful redwood trim, siding and moldings were studded with thousands of holes from the metal staples that had held the stucco wire to the building. The decorative terra cotta panels, too, had been pounded to shards in some places, or broken apart when the stucco was pulled off. But Hole and his crew were not dismayed. The building, they say, had "good bones." And a crack team of forensic contractors was ready to flesh those bones with their original 19th-century finery.

Each day revealed new details, fascinating pieces of the puzzle. Framing the turrets and the arched windows of the third floor was a pebbledash of local river rock set in mortar. Round wooden rosettes and bars, removed before the stucco was put on, had stamped their pattern into the wood above the bay windows. The first floor retail space, closed off in a remodel, was framed by sturdy cast iron columns.

For Hole, a professor of construction technology at College of the Redwoods and member of the Humboldt Historical Society, the project was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, a chance to get under the skin of the building and discover its many stories.

Much of the building's interior retained its integrity: Ornate oak pieces, shipped by Carson from France, still line the hallways, and two original grand staircases ascend to the offices on the third floor. The offices retain the fixtures and features of their youth: tall doorways, high ceilings, picture rail, steam radiators, wash basins. Almost all of these elements — the radiators, doors and basins, were removed, restored and returned to their original placement. Some were given environmentally-friendly updates, like the nonagenarian heating system ("In 1988 I had to finally retire that boiler," Coltra says. Maples Plumbing replaced it with a hydronic heating system.) Other details were restored to reflect the building practices of the past, which were green before green was a thing, like the vents underneath windows and above doors used to circulate fresh air.

But before any of this could take place, the walls had to be torn open and steel beams pushed inside to shore the original unreinforced masonry.

"There's no point restoring it if it's not structurally sound," says Nick Lucchesi of Pacific Builders, whose team helped retrofit the building under the direction of a Sacramento-based structural engineer, Ken Luttrell. The original fir columns used as support beams, made from single tree turnings, were relieved of duty and reintegrated into the design as aesthetic pieces, with some standing tall in what will be the NCIDC's new board room.

The columns were one of several elements Hole and his team believe were designed by shipwrights who made their living on the shores of Humboldt Bay, the only artisans at that time in the region with the technology to mill the intricate pieces that went into the design. Woodlab Designs, which recreated the removed turret, believes that piece must also have been originally crafted at the hands of shipwrights. Like other features of the building, the turret was recreated using reclaimed old-growth redwood, much of which came from old railroad trestles.

"The irony of it is that, probably without a doubt, a bunch of that wood was sawn down when the building was first constructed," Hole says. Carson was instrumental in establishing railway lines to ship his products out of the region; much of the reclaimed old-growth redwood now being used to restore his building may have been produced from his own mills during his lifetime.

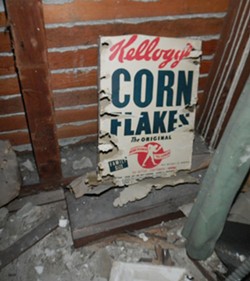

As the crew peeled back the layers of the building and then carefully stitched it back together, hints of its long history revealed themselves: The signatures of carpenters from several eras, penciled into the wood and covered by wallpaper; a room sealed off by renovations containing a small sink and an old box of cornflakes. Hole took pictures of it all, sometimes inching along scaffolding on his back to capture recently-uncovered ceilings and cubbyholes.

"I have a theory that whenever you find something in a historic building, you should leave it. People who take it home and put it on their mantle aren't honoring the story," Hole says. His photos are the only record of some of the building's witness marks, now covered again by reconstruction.

At the time of the Carson Block building's construction, much of the country was weathering an economic depression. Carson's employment of laborers to create Eureka's largest commercial office building was seen as an act of generosity and faith in his chosen homeland's future. In that respect, his vision aligns with those of Coltra and the many entities that have helped jumpstart the building's unlikely renaissance. Along with employing dozens of local workers, filling local hotel beds and restaurant tables with out-of-town workers and emptying the shelves of local hardware stores, those who have sunk their dreams into the Carson Block building see it as an investment that will pay off — with the revitalization of Old Town, the creation of new office and retail space, and an emblem of pride in Eureka's past and future. In its heyday, the building housed bankers, lawyers, doctors, a cigar shop, newsstand and procession of other businesses. Similar enterprises may make their homes in the three retail spaces that are being created on the first floor. Coltra says that many of the upstairs offices have already been rented, although he is closed-mouthed about who called dibs. Now that the retrofit is finished, further funding may appear to restore the once-grand Ingomar Theatre as well.

Some 15 months after construction began, the scaffolding has come down and the chainlink fence around the Carson Block building will soon be folded. The tall, curved windows of her turrets already gleam, framed by the dark red and deep forest green paint that pay subtle homage to the groves that bore her. The 124-year-old Carson Block building will open her doors and transform from fallen star to headliner in April, a fitting season for triumphant second acts.

Editor's Note: In the interest of full disclosure, Bill Hole, along with his wife Colleen, owns a minority share in the Journal.

Editor's Note: The original version of this story incorrectly stated that William Carson maintained the building until its sale in 1923. In fact, Carson died in 1912, and his family maintained the building. The Journal regrets the error.

The Puzzle

Carson had the tiling that originally framed the building’s windows shipped from San Diego. According to Bill Hole, the tiling originally comprised several different styles and patterns. When the stucco was installed, workers smashed the terra cotta against the framing, which broke several pieces. Hole surmises the workers at the time may have been trying to make the surface as smooth and uniform as possible so the stucco wouldn’t look lumpy. Still more tiling was broken when the stucco was removed; there wasn’t a single complete tile left intact. Preservationists used historic photos and shards from several different panels to develop a cast for replacement. The replacement panels — 225 in all — are made of cast sandstone instead of the original cast clay.

A Glittery Effect

Pebble dash, also called roughcast, is a slurry of gravel and mortar, and it usually doesn’t look this pretty. Like many other features of the facade, the original rock used in the pebble dash was pulled out and destroyed when workers removed the stucco. Analysis of the remnants showed that it was river rock. The team compared rocks from several local rivers. Originally, the Mad River was chosen to supply rock for the reconstruction, but its rock turned out to be “too gray” according to Hole. Samples from the Van Duzen River shore proved to be a closer match in color and texture to the original. The restoration team brought in around a ton of rock from the Van Duzen, which was set into the mortar by hand, with workers trying to mimic the spacing of the original. The result is a multi-colored, glittery effect that sparkles when the sun hits it.

Wooden Blooms

Standing Sentry

‘Reconstructive Surgery’

Additional Photos

Comments (4)

Showing 1-4 of 4

more from the author

-

Lobster Girl Finds the Beat

- Nov 9, 2023

-

Tales from the CryptTok

- Oct 26, 2023

-

Graduation Day: A Fortuna Teacher Celebrates with her First Grade Class

- Jul 18, 2023

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023