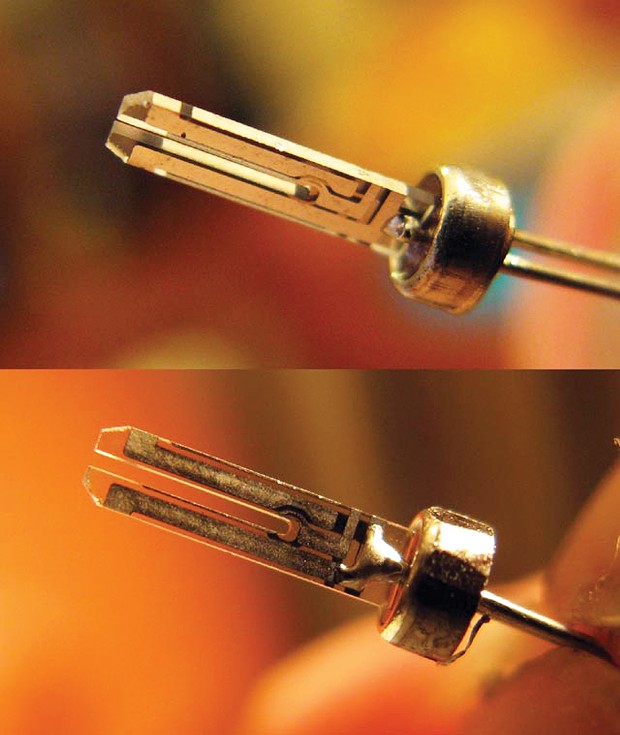

Photo by Chribbe76, public domain

A tuning fork-shaped quartz crystal is the key timekeeping component of most quartz watches and clocks. It's manufactured to vibrate at a steady 32,768 (2 to the 15th power) beats per second.

[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

The "quartz crisis" began in Tokyo on Christmas Day in 1969 when Seiko unveiled the world's first quartz watch, the Astron 35SQ. Designed by Kazunari Sasaki of Suwa Seiko-sha, the Astron achieved 100 times the accuracy of a regular mechanical watch by using a vibrating quartz crystal instead of a balance wheel for time keeping. Although the Astron originally cost ¥450,000 the same as a Toyota Corolla at the time — over the next 30 years, the price would to drop to where a perfectly serviceable quartz watch, keeping time to within five minutes a year, can now be had for $10.

While quartz technology brought accurate time within the reach of everyone, it would create a catastrophe for the Swiss watchmaking industry. Because Switzerland stayed neutral during World War II, the watch industry was unaffected, unlike other nations that shifted their watchmaking industry to timers for military ordinance. From 1945 until the early 1970s, the Swiss were able to capitalize on what was a virtual monopoly, accounting for more than 50 percent of the world watch market. All this changed with the advent of cheap and accurate quartz crystals; in the two decades following introduction of the Astron, the number of skilled workers employed by the Swiss watch industry fell from 90,000 to 28,000. Hence, what was a quartz crisis for the Swiss was a quartz revolution elsewhere, especially Japan, where companies such as Seiko, Citizen and Casio thrived.

Quartz crystals used in watches depend on the piezoelectric effect, discovered in 1880 by French physicists, brothers Jacques and Pierre Curie. Squeeze a crystal and it will generate a tiny electric current; pass electricity through it and it will deform. (The word comes from Greek piezein, meaning to squeeze.) Today, the piezoelectric industry accounts for $2 billion in annual business, thanks to its use in inkjet printers, gas wands and lighters, guitar and drum pick-ups, microbalances, atomic-scale microscopes and much more.

If you're wearing a watch, chances are that inside, safe within a tiny capsule, there's a little quartz crystal (about 1/10 of an inch long) in the shape of a tuning fork. When a miniscule current is applied, it vibrates at a constant 32,768 times per second, or hertz. That frequency isn't just a random number — the size, shape and plane on which the crystal is cut determines it. Why 32,768? It's 2 to the 15th. Halve it with a "flip-flop" circuit and you get 16,384; do that 14 more times via a series of flip-flops and you get a once-a-second pulse. If you have an analog quartz watch (with hands), you'll see the secondhand jumping forward in one-second increments.

The frequency of the quartz crystal largely determines its accuracy. The original Astron vibrated at 8,192 hertz (2 to the 13th), and was accurate to within one minute per year. Following the Astron, watches have incorporated higher frequencies (mostly 32,768 hertz) with a corresponding increase in accuracy. Other key advances included replacement of the analog hands with a digital face, originally LED (light-emitting diode) and later LCD (liquid crystal display).

It took awhile for the Swiss watchmaking industry to recover from the quartz crisis/revolution, but a glance at the advertising pages of any glossy magazine aimed at the upper crust will tell you what happened. The surviving firms (other than Swatch — another story) went for the top 1 percent of society with fancy — very fancy — mechanical watches. We're talking thousands of dollars for a Rolex to $1 million and beyond for, say, a handmade Patek Philippe or Greubel Forsey (Google "tourbillon" for a glimpse into another world). I doubt their well-heeled owners wear them every day — I can imagine no greater invitation to being mugged. They probably wear cheapo $10,000 Rolex Explorers on the street. Or one of those 10-buck beauties from Amazon.

Next week, we'll look at a watch that keeps time to within one second per year.

Barry Evans (he/him, [email protected]), who goes wristwatch-free, is rarely late.

Speaking of...

Comments (2)

Showing 1-2 of 2

more from the author

-

A Brief History of Dildos

- Apr 11, 2024

-

Eclipse!

- Mar 28, 2024

-

The Little Drone that Could

- Mar 14, 2024

- More »

Latest in Field Notes

Readers also liked…

-

Trouble on the Line: The Reality Part 2

- Nov 3, 2022