[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

My quest was simple: Find the smartest person in Humboldt.

Well, OK, actually it was a troublesome task. Almost as impossible as finding Bigfoot — except at least our smarties leave bona fide droppings around, indications of their intelligence for a keen person to pick up and stuff in her hunting cap.

My plan, too, was simple: neither scientific nor thorough nor responsible. I just went scattershot.

"Hey," I asked my colleagues. "Who's the smartest person in Humboldt?"

"We know it isn't any one of us," one answered helpfully.

"How about a brain surgeon?" said another. "You know, because of the saying: 'It isn't exactly brain surgery.'"

They named more potential bigsmarts: presidents, hoteliers, educators, writers, editors, politicians, historians, artists, scientists, doctors, financiers, judges. Then I got on the horn. First, the brain surgeons: One declined to play, and the other two didn't call back ... probably rightly thinking "this isn't brain surgery" and shuffling my messages off to dream-forget-land.

Next I tried Peter Hannaford, who one of my colleagues said might be "the smartest conservative" in Humboldt County (a label that sounds patronizing — like "the smartest blonde" — but I don't think was meant that way). Hannaford's a public affairs whiz — a U.C. Berkeley grad and Army veteran who's run several of his own companies and advised everyone from Ronald Reagan to 3M. He was, in fact, Reagan's public affairs director when he was governor of California, and later helped him get elected president. Hannaford's written umpteen magazine articles and edited or written a dozen books (including several about Reagan); the 12th, the second volume of the diaries of legendary syndicated newspaper columnist Drew Pearson, is at the publisher's right now.

"Are you the smartest person in Humboldt?" I asked him.

Over the phone, Hannaford's voice was gravelly, friendly and warm — pretty close to the way it's described on Voice123.com, where he's listed as a voice actor, a side thing of his. "No," the 82-year-old said. "I don't think there's any one smartest person."

But he knows a lot of smart people. Humboldt's stuffed with them: people "with native intelligence, a pretty good field of knowledge and able to adapt to practically any situation," in Hannaford's words.

"Name some," I said.

"Oh, no," he said. "I do that, I'm going to lose a lot of friends."

A better strategy, that's what I needed, some kind of shortcut through this purported thicket of smarties to The One. But what exactly was I looking for? The person with the highest IQ? EQ? The most financial success? Inventions? Degrees? Respect? Facebook friends? Something else entirely? What does it mean to be "the smartest?" And if we decide it means "of the highest intelligence," what is intelligence?

I consulted the web. It's debatable, turns out. For the last 100 years some have argued that there is a general, underlying intelligence in humans, called the g factor, revealed through a series of cognitive skills tests — and, in this theory, a person who does well on a math test can be predicted to do as well on a verbal test and all the tests of different mental faculties.

A light flickered: Mensa. (You know, "the high IQ society.") I Googled "Mensa Humboldt Calif," got frustrated over the local chapter's apparent lack of a proper Internet home (or maybe it's in the Deep Web and I'm not smart enough to find it) ... and stumbled backwards into local artist Elizabeth Berrien's website, where images of her wire-made creatures prowl. Heck, turns out the 64-year-old was admitted to Mensa at age 13 after they got a look at her school test scores and saw she ranked in the top .5 percent of the population. She's the one who recently got a National Science Foundation grant to work with scientists and a renowned origami artist to develop tiny fiber optic structures that can shape-shift when stimulated by a laser — something that could be used, perhaps, to fix errant brains.

The "wire lady" doesn't deny she's "one smart cookie."

"Everyone in my family's got all sorts of smarts," Berrien said. "We're usually trying to outsmart each other. There were five kids in my family, and my dad, to keep us from going nuts, would give us numbers games and math games and word games at the dinner table."

Sure, she was trouble in school, speaking out, ignoring the boring teachers, and flailing in art class until the art teacher tossed her some twine. Later, she says, she faked her way into jobs. Now her art's displayed in public and private collections all over the world and, at the moment, she's getting paid to think and to fiddle with some new equipment: a microscope with a digital camera attachment and tiny tweezers to handle fiber thinner than a human hair.

But, no, she insisted, she isn't the smartest person in Humboldt. There are many forms of intelligence, she said.

This sounded like a different theory I'd read about that suggests humans have multiple intelligences — at least nine, says developmental psychologist Howard Gardner, the Harvard scholar who began developing this theory in the 1970s. And these intelligences — unlike the mental faculties g factor proponents refer to — are independent of each other. That is, as Gardner puts it in a recent piece in The Washington Post, "... strength (or weakness) in one intelligence does not predict strength (or weakness) in any other intelligences" and "... all of us exhibit jagged profiles of intelligences."

Other theories clamor out there. And like Claire Knox, chair of Humboldt State University's Child Development Department, had told me in an earlier conversation, there's more than one way to talk about intelligence. Some people study how the neurology and biochemistry of the brain works, others explore the mind's processes ("thinking"), others examine the various models for assessing intelligence, and so on. It's a complex, evolving field. People used to say intelligence was a thing you either had or didn't have, Knox said, but now "most models today will talk about components of intelligence, or interactive types of intelligence — you know, like verbal and nonverbal."

But such models are really looking at how intelligence is expressed, not at an underlying structure. Neuroscientists peering directly into the brain, however, are making exciting discoveries these days that could tell us more about structure. Even so, "intelligence" is still just a concept, not a thing, Knox said, "and always when we are talking about it, we are talking about how we have interpreted certain kinds of behaviors as representing that concept."

This is where the popular press often gets it wrong, she said. While the science community considers a broad array of behaviors that represent intelligence, regular people tend to focus on a narrow, often wrong, set of ideas: that smart people always are going to do smart things, for instance. Or that a big vocabulary or vast knowledge of a subject means you're intelligent (when all these really reveal is what you've been heavily exposed to).

I asked Berrien what she thinks being smart, or intelligent, means. "It means being able to think on one's feet, to adapt to sudden shifts and changes in one's circumstance ... always curious, never bored."

Look at Eric Hollenbeck, she said, founder of that hive of innovation, Blue Ox Millworks. Or Libby Maynard, the Ink People cofounder. Or Berrien's own daughter, Emma Breacain, executive director of the Literacy Project, a Rutabaga Queen and other things.

Even so, Berrien kindly said she'd track down some other local Mensans for me.

"Oh, God," said Mensan Jake Williams; Berrien had sent him to me. A long-time newspaper man, he was not impressed with my mission or with his own potential role in it.

"Being a Mensan is about passing tests," he said, dismissively. If your IQ (or other relevant) test scores land you in the top 2 percent of the population, then you're eligible to apply to get in. That's it. And these days, you've got to be at least 14.

"You know, I think high intelligence is probably misunderstood a lot," Williams said. "It does not guarantee success in anything. Amongst Mensans I've known, we've had people who were Caltech-type folks and we've had people who went to community college and never went any further. ... You have a different level of understanding of the world, I think, but I don't know that it's any better or worse than anyone else's understanding; it's just different."

Mensans he's known also have trended toward the nongregarious. But anyway, he said, he knows people way smarter than him — more widely informed, better educated, "more with it." He started listing them.

"Ryan Hurley, your Captain Buhne," he said, referring to the Journal freelance columnist. Ken Gatlin, writer and artist and active Greek Orthodox Church member. Stephen Sottong, Mensan, writer, good at math and engineering. Williams' son-in-law Neal Feuerman, a Fortuna anesthesiologist. Retired government worker Karen Suiker. Humboldt State University professor emeritus William Wood, a chemical ecologist.

My mind had wandered off and was toying with Berrien's tiny tweezers. They'd triggered a memory, something I'd read about a guy up at HSU also working with dimensions smaller than a human hair. Something to do with gravity.

Professor C.D. Hoyle wasn't in when I called HSU's physics department. Later, he phoned me from Harvard where he's been spending part of his year sabbatical helping to build a new telescope that might help particle physicists better understand dark energy — the stuff that makes up nearly 70 percent of the universe and is responsible for speeding up its expansion, but about which not much more is known.

But he continues to mentor his Humboldt students from afar. They're undergrads, yet Hoyle treats them like grad students (there's no graduate physics program at HSU), putting them to work in his gravitational research lab. Right now, with grants from the National Science Foundation and elsewhere, he and his students are working on an experiment that also could reveal more about dark energy, dark matter and the essence of space and time. They're designing and building a special torsion pendulum to observe how gravity behaves when objects get very close together — closer than the width of a human hair. Nobody's done this close of a measurement before. Also, Ace Hardware doesn't carry the pieces for building such an instrument, so Hoyle's students are machining everything from scratch.

The aim is to see if the two big, but conflicting, functioning models of how the universe works — relativity and quantum mechanics — can be reconciled and lead us to that elusive beast, the Theory of Everything, an all-encompassing set of natural laws that explains how everything works.

Einstein's theory of relativity explains how gravity works, and blackholes and the motions of planets and galaxies — the large-scale stuff. It's how we get our GPS systems to work properly, said Hoyle. Quantum mechanics explains how the can't-see stuff works — things on the molecular, atomic and nuclear scale, things like light. It's the reason we have cell phones and other such technology.

"But the problem is, those two models of nature really don't describe the same universe," Hoyle said. "They're mathematically inconsistent with one another. In other words, you can't explain some things with relativity that quantum mechanics can explain [and vice versa]."

String theory is one candidate for unifying these two. And one of the predictions of string theory is that gravity behaves fundamentally differently than how Einstein predicts it should when you get objects very close together.

If Hoyle and his students' pendulum shows that gravity does behave differently on the microscopic scale, then that's one more feather in string theory's cap. And if not? Well, that's good information, too.

OK, I'd found my quarry. Hoyle scoffed.

"I would find it incredibly unlikely that I would be the smartest person in Humboldt, based on probability," he said, laughing. Echoing everyone else so far, he said there's all kinds of intelligence and all sorts of smart people. And he pointed me back toward the forest.

After struggling with physics theory, I needed a break. How about a word person? One had been suggested: HSU emeritus professor of English Tom Gage. I met him at a cafe in Old Town, he started talking and immediately I was crying for some quantum with my coffee. Gage — who was dressed nattily in a brown blazer and black turtleneck — is an affable guy, fun to talk to ... but also a theorist. As flamenco guitar poured from the loudspeakers, Gage told his story — after first proclaiming he is "woefully unqualified to be the smartest person in Humboldt" and woefully unqualified for every job he's ever had.

His mother raised him in Oakland, where they moved around a lot; in high school, Gage worked to help pay the rent. While an undergrad at U.C. Berkeley, he hitchhiked one year toward a kibbutz but ended up in Damascus. In 1976, he moved to Humboldt and taught English at HSU for the next 30 years, developing the Masters in Teaching English program and the Redwood Writing Project and helping a student design the award-winning software Writing Trek. He kept traveling: to China, Greece, Turkey and Syria (where he went as a Fulbright scholar). Since retiring, in 2006, he's just sped up. He's written, co-written and edited 20 publications, four of them historical nonfiction books (one, American Prometheus, is about his great-grandfather Captain Bill Jones, "the engineering genius behind the steel empire of Andrew Carnegie," as iTunes puts it). His No. 1 pet project is spreading the combined education gospels of Turkish inspirational figure Fethullah Gülen and the late James Moffett, who wrote the influential Teaching the Universe of Discourse, which basically says kids are individuals — not little robots conforming to standardized curricula and tests — and should be taught as such.

"It's a theoretical structure based on 'what is happening,' 'what happened,' 'what happens,' or 'what oughta happen,'" said Gage.

So, but ... what does it look like? Consider an English department, he said — literature studies on one end, composition studies on the other, and never the twain shall meet. But they should.

He recited a Langston Hughes poem. Now, he said, in a classroom, some kids could perform an improv skit based on it. Another group could script their performance. A third group could write a report about it. And a fourth could write about what ought to happen in the poem — the utopia.

It is a unified field theory for teaching composing and reading, said Gage.

As for the Gülen part of it, Gülen is a former Turkish imam, now living in the United States, who inspired a movement fostering international dialog between people of all faiths (and no faith), scientists, and others with the goal of teaching people to use their knowledge for the common good — to be people of action.

Gage started a program that, so far, has resulted in at least 30 schools here in the United States (including Humboldt) "linking up" with schools all over the world. For instance, he said, he had 10th graders at Six Rivers Charter School doing the same homework as a classroom of kids in a town in Morocco.

He hopes this model will further peace and understanding in the world.

Gage got me thinking about kids and school and different ways of learning, and also about something else Knox, who's studied intelligence and giftedness for years, had said: that when she thinks about the most intelligent people she knows, what comes to mind are people who aren't necessarily highly educated. "But they are able to think and process and pay attention and organize and sort and evaluate and reflect — to engage meaningfully in the world in a variety of ways that show insight."

I figured it was time to look up the guy several people had said I absolutely had to call: Eric Hollenbeck. Here was someone who'd gone from a can't-read high school dropout working in the woods to developer of the one-of-a-kind Blue Ox Millworks in Eureka, which honors Victorian-era craftsmanship, creates custom woodwork for international buyers, teaches veterans and hosts high school students who learn to make things and run their own radio station.

People say he squirrels everything he learns into his brain, ready to pluck out on demand.

Hollenbeck laughed when I asked him if he was the smartest person in Humboldt.

"I'd be pretty surprised at anybody who answered yes to that question," he said.

But there are brilliant people here. And he does consider himself, at 68, "one of the elders."

Still can't read worth a hoot, though, he said, at least not without closing one eye to trick his brain. The trouble is, he sees in 3D — in pictures — and so when he looks at a page, especially if it's computer-generated, the spaces on it can link up to form what typographers call rivers. And the wall of text on the left side of the river will jump up and the text on the right will recede.

This "trouble" is truly an asset, however. It's what allows him to create what he does. Right now, for example, Hollenbeck is building a replica of the hearse that carried Abraham Lincoln. It's for the 150th anniversary of Lincoln's death. Hollenbeck had to draft the plans from the lone existing photograph of the hearse, which was shot at an angle, and one known dimension, the size of the back wheels. So he worked all this out with a pencil and an architect's scale, figuring the loss of scale due to the picture's angle, and sent the plans off to the people in Springfield, Illinois, who commissioned the work. They'd also asked some hotshot designers at Ford-Mercury to work up some plans with a computer. The two plans were identical.

"And the engineer there at Ford-Mercury says, 'Wait a minute! This is drawn in pencil,'" said Hollenbeck. "'We had a heck of a time with the CAD system coming up with loss of scale! How'd he do that?' And they told him, 'He's some guy up in the woods of Northern California. We think he used a slide rule, a Ouija board, a small bonfire and a goat.'"

Hollenbeck's a storyteller — says he has "a trap-jaw memory for the spoken word." In fact, his auto shop teacher got him back into high school after brokering a deal in which he could take four hours of auto shop and one hour of English — and the English teacher had to let him do all his work in poetry. He got a C in English — an A for artistic effort and an F for punctuation.

"Everybody has got some asset that compensates for any handicap they have," he said. "A wise man plays to their strengths. Only a fool plays to their handicaps."

He said the smartest person in Humboldt is the person who's still learning daily. "Because, the minute you think you've got it, you've just dropped into a well of stupidity."

The smartest people Hollenbeck knows seem to have been shaped by this wild, North Coast land: lumberman George Schmidbauer; the late traditional Yurok craftsman Axel Lindgren Sr.; artist and writer Julian Lang, of the Karuk Tribe.

"We're solvers of problems," he said. Retaining knowledge passed down for tens of thousands of years. Or coming up with new ways to live, devising tools to work with the biggest trees around. Figuring out how to live comfortably off a wet, but rich, land.

You could call it the Humboldt factor.

My search had to end. It was getting late and the rain was coming down hard. Intelligence had turned out to be a shapeshifting creature, leaving obvious startling tracks then slipping shyly back into the woods. And anyway, as gravity man Hoyle had told me, the smartest person in Humboldt probably is just a kid, maybe a student at the university. Who knows what that kid'll be doing in 10 or 20 years?

Or maybe I hadn't glimpsed any signs of the true beast at all. Knox had warned me that the truly intelligent don't often stand out as the most cool, successful and "intelligent" people. They're more likely the overbearing misfits who ask weird questions, take stuff apart and act like general pains in the butt. They're the people other folks call a little bit stupid.

Speaking of...

-

Robert William Astrue: 1928-2023

Feb 13, 2024 -

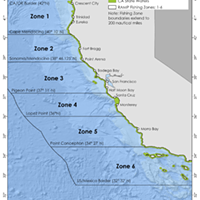

Local Commercial Dungeness Crab Season to Open in January

Dec 20, 2023 -

Susan Ellisa MacConnie: 1952-2023

Oct 1, 2023 - More »

Comments (6)

Showing 1-6 of 6

more from the author

-

From the Journal Archives: When the Waters Rose in 1964

- Dec 26, 2019

-

Bigfoot Gets Real

- Feb 20, 2015

-

Lincoln's Hearse

- Feb 19, 2015

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023