'Queen City of the Ultimate West'

Rob Holmlund is asking Eurekans to dream big

By Linda Stansberry [email protected] @lcstansberry[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "15",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

First impressions don't tell the whole story. If you don't have a city planner's acumen or an architect's eye, you might drive through the most densely populated city on the Redwood Coast and assume she's a cheap thing, welcomed as you are with Broadway's peeling paint and strip-mall feel. But if you go past those layers and get to know her, you'll find a mature, vibrant metropolis that has — according to its community development division — been restrained far too long by prudish zoning laws. But now, thanks to a charge led by Rob Holmlund, the city's director of development services, the Eureka City Council and Planning Commission are considering changes to the city's general plan aimed at allowing the city to finally become the diva she was always meant to be.

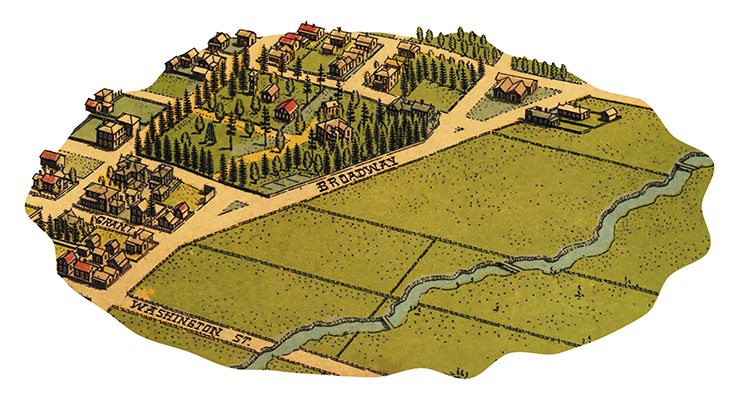

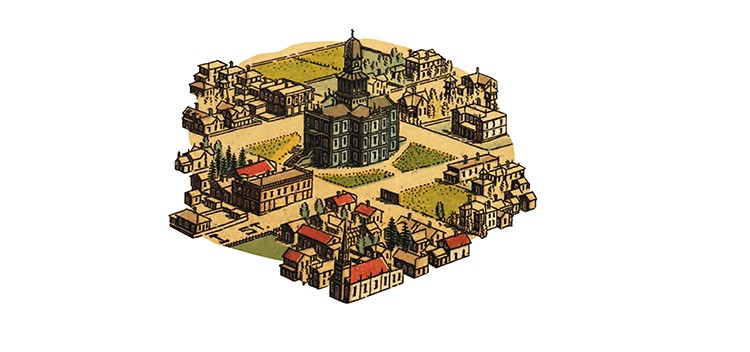

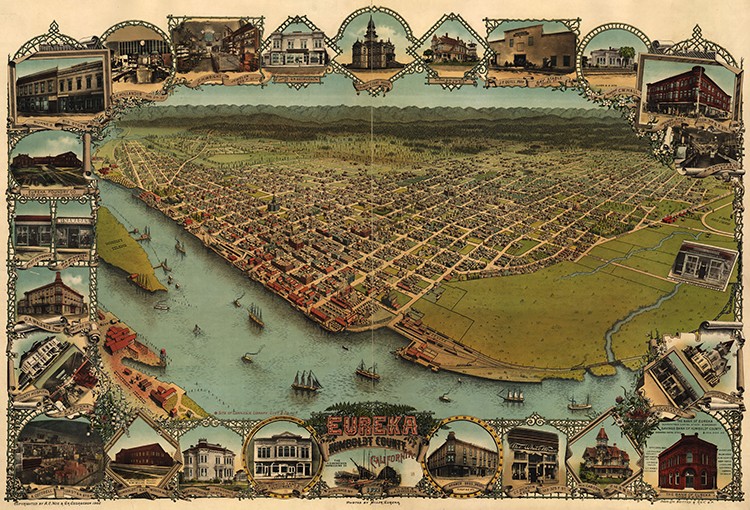

The truth is, Eureka was never meant to be a nice little town. It was built with the bones of a dynamic port city. Its blocks are long, originally sold in 25-foot-wide lots that allowed families to build small homes across from sprawling multi-lot mansions. Unlike many other West Coast cities, almost all of Eureka proper was developed before the advent of modern zoning codes. In 1850, after expelling the native Wiyot, white settlers began gnawing away at the redwood trees that hugged the coast of the bay. Lumber camps became a lumber town, with boards traveling by freighter to San Francisco and also transforming into local buildings as humble as the 2,900-square-foot Globe Building, one of Eureka's oldest extant buildings, to the ornate Carson Mansion. As the city expanded outward from the port, it developed in a grid system, with lines intersecting lines, almost every street having an alley that would serve for deliveries and garbage collection. Automobiles were not the norm then but the streets accommodated horses and, for a time, a trolley system that took residents from the bustling docks to the edge of Harris Street, where, in the 1930s, the city ended and the forest began.

With no development standards in place, young Eureka's growth could have been haphazard. In cities that sprung out of medieval villages, for example, the inner city is often a warren of winding streets. But the grid system kept things more or less aligned and the abundance of construction material means most of her old buildings are well built and still standing, a century and several dozen earthquakes later. Almost the entire city of Eureka was built between 1850 and 1966, and the architecture reflects more than a century of changing tastes. Wedding cake Victorians sit cheek to jowl with sturdy Craftsmans; the Tudor Revival-style Eureka Inn gazes at the neoclassical Morris Graves Museum of Art. Italianates, Eastlakes, Spanish Colonial Revival, step-back row houses, bungalows, clapboards, cottages and frames — Eureka has them all. And almost none are currently legal to build within city limits.

The story of why is the story of much of American infrastructure development in the latter half of the 20th century, which was almost entirely focused on a car-centric culture and the segregation of different building uses (commercial vs. residential). Think post-World War II suburbs, strip malls and highway overpasses. Although Eureka was already mostly built, it needed to adopt some sort of zoning and building regulations. And tragically (in Holmlund's opinion) it chose one that was (also in Holmlund's opinion) entirely inappropriate for Eureka.

"Eureka was like a kid that was trying to keep up," says Holmlund, who says he first noticed the issue when he started with the city in 2014.

While reviewing the zoning code, Community Development staff found that whole paragraphs of it were lifted from guidelines developed for Iowa. This, Holmlund says, is counterproductive. The suburban sprawl that dominated much of post-WWII urban planning, with cookie cutter two-story houses and cul-de-sac streets (planners call them "lollipops"), was never going to be right for what boosters in the 1930s called "The Queen City of the Ultimate West." The fact that almost every square inch of the city was already developed, combined with an economic downturn in the late 20th century, meant most of those original historic buildings were spared the dubious virtues of urban renewal. But according to Holmlund, those onerous zoning codes have had a stagnating effect on the creativity and economic growth of the city's developers and homeowners.

To get a good idea of what the current codes mean in practice, drive anywhere west of Broadway, the last part of town to be developed. The buildings you'll see there are low, three stories tall at most, and surrounded by large parking lots. These were all built after the passage of the current development standards. (Much of North Broadway once looked like Old Town, but it was razed and redeveloped in the 1960s.)

"The Bayshore Mall, for example, was exactly what our development standards called for," says Holmlund.

Also lost after 1966 were neighborhood bakeries, markets and cafes, as the wisdom of the day dictated that commercial and residential zones should be separated. The few neighborhood markets that remain, such as Pat's Market (11th and M streets) or C & V Market (on F Street near Wabash) were grandfathered in. City planners in the golden age of the automobile probably couldn't picture a time when people would be discussing locavorism or prizing infill. It may have sounded clean and efficient in principle, segregating where people live from where they shop and eat, but, in practice, it means a bigger carbon footprint, with more people driving to reach amenities and less interaction between neighbors. Mixing residential and commercial uses, Holmlund argues, could also benefit business owners by having more people to keep an eye on storefronts once they're closed.

"We had this beautiful ecosystem of neighborhood markets and bakeries," he says. "We want these allowed instead of making them illegal."

Relaxation of some development standards could also mean improvements to Eureka's notoriously tight housing market, allowing homeowners to build mother-in-law units and developers to create multi-family buildings, duplexes and triplexes, a term known as "gentle density." While most people think of multi-unit housing as less-than-attractive apartment complexes, the city currently has quite a few converted Victorians, stacked duplexes and bungalow courts. They're easy on the eyes. They're also impossible to recreate. Holmlund and his staff recall many conversations with frustrated homeowners who wanted building permits for projects similar to what they saw on their neighbors' property but were turned down.

"The city council has been receiving complaints for years about the planning staff," Holmlund says. "They hired me to fix this. What I found was planning staff were taking hours to go through the books to try and help people understand the rules. I had to ask why the rules were so counterproductive."

In a September 2017 presentation to the city council and planning commission, Holmlund said it was time to entirely overhaul the system, getting rid of outdated prescriptive zoning that contained language allowing some business districts to have pony riding rings and apiaries, for example, but not cell phone repair stores or yoga studios.

"At first, I thought we could fix the zoning code one flawed piece at a time but in early 2017 I decided that the only logical course of action was to start entirely from scratch and draft a new, modern, sensible zoning code," Holmlund says. "Coincidentally, we were in the middle of a General Plan Update, which provided us with the opportunity to fully zoom out and look at all of the city's development-related policies."

The new General Plan, which came out of 10 separate hour-long study sessions attended by the the city council, planning commissioners and development services staff is due to be adopted by the council in September. State law requires the zoning code be modified in response to the General Plan, which could happen as early as January.

The Community Development staff also put together an interactive workshop to get community input for potential changes. More than 200 people attended a Nov. 28 meeting at the Wharfinger Building: property owners, residents and commuters. Invited to "set the tone for their zone," attendees weighed in on building heights along Broadway, residential duplexes, mixing residential and commercial uses and their general feelings about what the town needs to thrive.

Robert Maxon, a local developer and owner of Globe Properties (which includes the historic Globe Building), says he has run into zoning obstacles before when considering mixed-use development along the waterfront. The workshop showed him how many community members were invested in positive change for the city.

"It was standing room only, with people pushed out into the lobby," he tells the Journal. "People seemed really grateful for the opportunity to weigh in. There was a really nice cross section of people attending."

Should the community's vision come to pass, it could radically change the look and feel of Eureka. The majority of people who voted, for example, would prefer a Broadway with more street trees and pedestrian walkways rather than billboards and single-story storefronts. People also seem to want bigger buildings, up to five stories tall in most districts (Henderson Center being the exception) and allowing more neighborhood markets.

Because so much of the city is already built, Holmlund and his colleagues believe the future of development in Eureka will depend upon infill, building upon vacant lots or rebuilding existing buildings to be taller. Holmlund touts this as an environmentally friendly way to build, as new development will use existing streets and infrastructure.

So, what's the benefit of building taller and is anyone actually itching to do it? This hinges on an astonishing fact: In the five-county region of Humboldt, Del Norte, Trinity, Humboldt, Mendocino and Lake counties, Eureka is home to the only building that's more than five stories tall. This presents an environmental and economic advantage for the town, according to Holmlund, creating more of that "gentle density" by building up rather than out. When the city completes its overhaul of the zoning codes, it can start courting investors who might want to do some of these bigger projects, or incentivize current business and homeowners to increase residential and commercial space.

Kash Boodjeh, an architect who has worked on local projects like converting a muffler shop into Arcata's Café Brio and the historic rehabilitation of Eureka Victorians, isn't convinced these changes will stimulate the kind of renaissance Holmlund is pitching. Bigger obstacles remain, such as the California Coastal Commission, whose oversight of waterfront properties has stymied past development proposals. And taller buildings? Unlikely, Boodjeh says.

"With the earthquake faults that we have, the kind of soil that we have ... they don't necessarily allow for the sort of heights that we need to happen relatively inexpensively," he says. The groundwater levels in Old Town, for example, make it impossible to put underground transformers there. Tall buildings requiring elevators would need a separate power source. All of this gets expensive and, Boodjeh says, the money is just not there. We have the same kinds of codes and regulations as the Bay Area, without the cheaper construction materials, labor pool and commercial demand.

"For us to do what they do in San Francisco, we need to charge San Francisco rates. We're not anywhere near that," he says. Will mixing residential and commercial uses help mitigate these costs, with our impacted housing market getting a boost by stacking apartments on top of storefronts? Maybe, Boodjeh says, but it's a big risk for developers.

Holmlund says he doesn't know yet whether or not developers will bite on this new opportunity, but at least the city won't be saying no.

To see Eureka's future, Holmlund says you should look back to its past.

"We want to promote what ultimately became Old Town rather than what became Broadway," Holmlund says.

Of course, Old Town's current incarnation is evidence of several near misses. In the 1970s, the district, which is now on the National Register of Historic Places, was scheduled to be razed and become the new site of the highway. Thanks to the efforts of then city Councilmember Jim Howard and others, the district was saved and restored. Had that not happened, those beautiful old buildings would no doubt be ghosts under squat little storefronts with big parking lots, built under the strictures of a Midwestern zoning code. When walking through Old Town, Holmlund points toward other lost buildings: An Italianate that is now a vacant lot, the old City Hall that became a parking lot.

Parking remains one of the biggest bugaboos for people who might otherwise embrace a densely built, walkable city. While there are several free and paid parking lots in Old Town, city staff continue to receive complaints about a lack of street parking. In the November workshop, a majority in attendance said they would be willing to walk between six to 10 blocks at the most to their destination. Holmlund says there's an error in perception when it comes to parking, with six to 10 blocks equating to roughly the same distance someone would walk if they parked in the Bayshore Mall parking lot and did the course of the mall.

As the date to finalize the changes approaches, there might be pushback against the idea of more liberal height restrictions. At a December city council meeting discussion about the sale of city-owned property in the Bridge District, slated to become a high-end Recreational Vehicle park, several business and home owners spoke out about the loss of their views from the hill, which had been pristine waterfront for many decades. Should Eureka build up, some people who have been accustomed to having the same vantage for decades might be understandably upset.

"It's a complicated topic," Holmlund says. "But people don't actually own a view unless they have a view easement."

Building up might also cause complications for the waterfront, where the city has invested a substantial amount of money into creating a walkable boardwalk and continues to solicit ideas and investors for new development. If that development went too high, it could cast the boardwalk in shade, creating a chilly walk for tourists.

And, of course, there are things zoning simply cannot fix, such as the alignment of the highway and the problems that many tourists and business owners have with a large, visible homeless population. That homeless population, often mentioned by tourists in online reviews of Old Town, was also cited as a big obstacle to economic growth by attendees at the November workshop, with people saying the city was "overrun" and they don't feel safe on the street after businesses close. Holmlund has said in the past that homelessness should be considered a county issue, not a city one.

"Any county seat has challenges that neighboring cities don't have," he says, adding that for all of the skepticism, the area has enormous economic potential. We have 20 percent of the county's population, but 40 percent of its businesses. Grow those businesses — ideally upward — and you have the kind of sales tax revenue that could make a big difference.

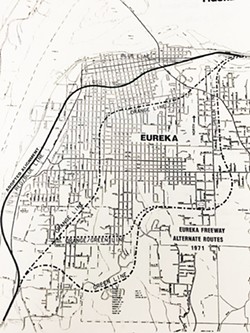

While there were at times plans to reroute U.S. Highway 101 away from the heart of the city, there don't appear to be any options to do that now, meaning that however many new buildings, pedestrian crossings and street trees we get, we will almost certainly always have traffic. (We should count our blessings, however, for another near miss, because in the 1960s the state envisioned a giant overpass that would cross the entire town diagonally from the southwest to the northeast, leaving parts of the city in shade. It never happened but the state went so far as buying easements along the route that were only recently put back into general use.)

Standing next to the Globe Building, now home to jewelry company Whiplash Curve, Maxon says he is looking forward to the potential flexibility zoning changes could create. Although he has no plans to change what was once the Buhne General Store, built in 1958, there are other properties in town that could benefit from what he calls "a more thoughtful, creative process." Should the city's vision come to pass, Maxon may be the kind of developer the city will start courting.

"We've lost a lot in Eureka," Maxon says. "But we have a lot, too. I think this is an exciting time."

Linda Stansberry is a staff writer at the Journal. Reach her at 442-1400, extension 317, or linda@northcoastjournal. Follow her on Twitter @LCStansberry.

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1

more from the author

-

Lobster Girl Finds the Beat

- Nov 9, 2023

-

Tales from the CryptTok

- Oct 26, 2023

-

Graduation Day: A Fortuna Teacher Celebrates with her First Grade Class

- Jul 18, 2023

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023