'Perfect Storm' Has North Coast Marine Ecosystem Reeling, Abalone in Crisis

By Kimberly Wear [email protected] @kimberly_wear[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "15",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Cynthia Catton's voice catches a bit as she describes diving along the North Coast this summer to survey the region's red abalone stock as part of annual state monitoring efforts. She had known the situation was bleak but that didn't prepare her for what she would see.

"At all of the sites we saw a huge amount of death," the environmental scientist says. "We saw abalone dying and dead and being eaten by urchins, and we also saw a lot of empty shells. We saw, in most places, more dead shells and dying abalone then we saw live abalone."

Catton, a member of the California Department of Fish and Wildlife's marine invertebrate management team, pauses a moment before continuing.

"It was a pretty devastating year to be a diver in the water and doing these surveys," she says. "I don't know how to express our reaction. It was just really devastating to see this level of impact to this population."

In just a few short years, the Northern California waters stretching from Sonoma to Southern Humboldt have undergone a dramatic transformation, with stretches stripped bare of their once varied marine life in a phenomenon known as "urchin barren."

"We are seeing really huge numbers of purple urchins for over 100 miles of coastline pretty continuously, which is a really outrageous scale," Catton says, noting that even a 1-mile expanse would have been considered significant in the past.

Gone are lush underwater forests of bull kelp tendrils swaying in the ocean current that provided shelter for a wide array of fishes and other sea creatures, and also served as the primary food source on which abalones depended.

Now the abalone are starving, simply unable to compete with the voracious appetites of marauding armies of spiky purple sea urchins that, in some places, have even scoured the calcified pink algae from the region's rocky reefs in a relentless march for food.

They are, Catton says, "the goats of the sea," eating everything in their paths.

Amid that backdrop, the North Coast's abalone stock has plunged into a rapid decline. First, the mollusks stopped reproducing. Then starvation symptoms set in.

The first signs surfaced in 2015 with divers reporting abalone falling off rocks after their strong muscle adherer — the part called "the foot" that is so coveted by consumers — became too shrunken to hold on.

Over the next two years, the scale of the famine would escalate. When Catton and a team headed out to beaches at the center of the fishery in 2017 to see what divers were bringing in, they found 25 percent of the 6,000 abalones observed were wasted with hunger.

"Normally, we would see one. Not 1 percent. One," she says. "It's really, again, an unusual thing, a very unusual thing, and we saw this impact across all of the sites in Sonoma and Mendocino counties and Southern Humboldt."

The numbers from that summer dive were even starker: Ten sites in Mendocino and Sonoma counties showed abalone populations had declined by an average of 58 percent.

That led to the state Fish and Game Commission's unprecedented decision in December to shut down the entire 2018 recreational season with a one-year sunset date for another review.

Many of those who addressed the commission — either via written comments or in person — were against the move while acknowledging the dire straits of the abalone. They advocated instead for severe restrictions, including drastically reducing the allowed catch and increasing the size limit from 7 inches to 8 inches.

Several expressed fears that a closure would forever lock away the last vestige of California's once great abalone fishery, citing how four other species found farther south — blacks, greens, pinks and whites — have been off limits for decades, both commercially and recreationally, but still haven't rebounded.

"We don't have a good track record of closures and reopening," Wayne Kotow, president of the group Coastal Conservation Alliance, told commissioners during the meeting. "I understand ... wanting to close because the population is that low. It is scary. I see the numbers. I get it. But my problem is we go through this process and we never get to open them back up."

He also raised the fiscal downside, especially for areas like Fort Bragg, which relies heavily on out-of-town divers coming to its shores, giving a boost to local businesses in the isolated Mendocino County town.

The total annual economic impact to coastal communities in the fishery's epicenter is estimated to be around $26 million — with up to 250 jobs on the line.

There were also concerns that taking the divers who cherish the tradition — and play by the rules — out of the water would leave an already vulnerable abalone stock open to increased pressure from poaching, a scourge that officials acknowledge is likely to increase with the closure.

Just last month, the Mendocino District Attorney's Office announced the settlement of three poaching cases, two of which involved restaurant owners caught in the black market purchase and sale of the treasured delicacy.

But for others at the commission meeting, there was simply no other choice but to shut the season down.

That included Humboldt County resident and abalone diver Brandi Easter, who traveled to San Diego to address the commission, telling them "the abalone fishery needs our stewardship not our selfishness."

Easter held up a bleached shell as she spoke, saying she almost didn't take an abalone on her last dive back in October after seeing piles of similar ones down below her, void of their once vibrant red coloring.

"This year I dove a variety of areas throughout the season and it was extremely heartbreaking," she says, emphasizing that her support was for a temporary closure. "For me, to dive in these areas that were once thriving and abundant with life that are now kelp-less urchin barrens with atrophied abalone and empty shells, I do not need to see transect data to know there is something amiss out there."

Sonke Mastrup, marine region program manager for fish and wildlife, acknowledged the apprehension over what a closure could mean, while also noting that further restrictions put into place in recent years had failed to stem the tide of the abalone's decline.

"I'm an avid abalone diver, so I get the concern," he said. "But I think that Brandi put it best, which is that if we are truly conservationists, let's step up and be conservationists."

But he vowed that fish and wildlife won't "close it and just walk away.""All we can do is make a commitment that we won't do that, and I'm personally invested," Mastrup said.

Several commissioners described the move as one of the most difficult decisions they'd ever had to make."I know that I'm disappointing some people who have become great friends in the last year or so ... It breaks my heart that we have to do this," said Eric Sklar, the commission's president.

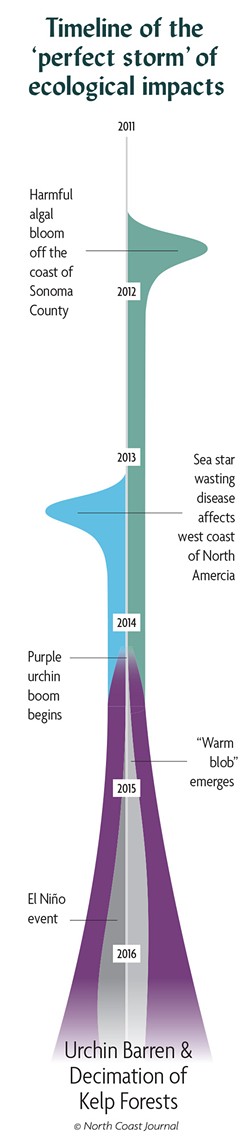

The abalone are in many ways just the latest casualties in what scientists are calling the "perfect storm," a series of ecological events that have thrown the North Coast's natural balance off kilter.

"I kind of curse Mother Nature sometimes because she's horrible at experimental design," Catton says.

The first rumblings of trouble began back in August of 2011, when an outbreak of toxic algae off the Sonoma County coast caused a massive die off of marine life there. The emergence of the mysterious sea star wasting disease followed two years later, wiping out about 80 percent of the colorful creatures.

With one of its main predators removed, the purple sea urchin population then exploded just as waters off the North Coast began heating up when the so-called "warm water blob" showed up in 2014, followed by the "Godzilla" El Niño of 2015.

Despite the colorful monikers handed down by scientists, the climatic events spelled disaster for the region's ecosystems, especially bull kelp forests, which in some areas are now more than 90 percent smaller than previous years.

"Complicating matters is bull kelp can be extremely sensitive to ocean temperatures and abalones are slow growing," says Brian Tissot, a professor and director of Humboldt State University's Marine Lab located in Trinidad.

The urchin surge, he says, "added insult to injury."

Because "nutrients and temperatures go hand and hand," Tissot says the best hopes for the kelp — and in turn the abalone — is a return to the region's traditionally cooler water conditions.

Meanwhile, the hope is the 2018 fishery closure will give the abalone some time to stabilize. One of the reasons that's so important is because of how the sea snail tucked into an ornate shell reproduces — basically by sending sperm and eggs out into the water. For the two to successfully meet, there needs to be enough abalone near each other.

If the population gets too small, it simply can't rebound, which is what has been occurring down south with other varieties of abalone.

"We are trying to avoid exacerbating a really bad problem to give the fishery a chance to slow down its decline while conditions remain so poor," Catton says.

A similar story holds true for bull kelp and scientists see preserving what pockets are left as paramount to bringing back the waxy canopies that once blanketed the coastline.

"There's the potential of a really small patch to produce spores to cover a region of some sort," Catton says. "If we can maintain or enhance a network of kelp patches where spores are being produced to supply spores for the surrounding area that might be something we can tackle and, if we can concentrate that effort in a targeted way, then we'll have the best chance of success rather trying to have a more diffused effort across the entire coastline."

But unlike its southern cousin the giant kelp, bull kelp grows as a single stalk and dies off each year — basically an annual marine plant rather than a perennial — which makes it more vulnerable to hungry urchin mobs that can hinder its ability to reestablish new growth.

To help the kelp along, Catton is partnering with urchin divers and community groups to set up pilot projects near the urchin processing plants in Fort Bragg's Noyo Harbor to target the spiky critters as a possible stop gap measure.

But with the main culprit being a series of environmental factors, it's still unclear how things will play out. The hope is that conditions will begin to normalize and the ecosystems off the coast can begin to rebuild.

"There's a lot more research that needs to be done to understand how dire is this situation," Catton says, "and once we know that, we can figure out how we can help it along a little bit."

Catton says this wave of an unprecedent conditions "fits very well with our expectation of climate change," with wide-reaching rather than regionalized events — like the sea star wasting disease that stretched along the entire Western coastline — as well as familiar phenomenon like El Niño but in more frequent and extreme forms.

There's also the emergence of strange, never-before-seen behaviors, like the way abalone in stricken areas are crowding into the shallows in a desperate bid for food, sometimes stacking themselves on top of each other rather than dispersing at a variety of depths.

That alone raises their vulnerability because having enough numbers at depths beyond 25 feet — out of the range of free-divers — gives abalone a certain lifeline by having a population removed from fishing pressure.

"We don't really know what to expect as we move into new oceanic conditions," Catton says.

Tissot agrees.

"If this is the new normal, we're going to have a lot of long-term problems," he says, noting the kelp off Trinidad hasn't yet seen the same devastation as Shelter Cove and points south, but researchers are monitoring the situation. "Things are changing and these cold water organisms like abalone and rock fish and crab, there's a potential these are things that might not be here in the future."

Kimberly Wear is the assistant editor at the Journal. Reach her at 442-1400, extension 323, or [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter @Kimberly_wear.

Editor's note: This story has been updated to correctly attribute quotes to Sonke Mastrup.Speaking of...

-

Eco Cemeteries, Flags, Impacts and Foods

Apr 12, 2024 -

Sunken Seaweed's Dual Mission

Apr 11, 2024 -

Alternative Energy Brainstorming with Billionaires

Apr 11, 2024 - More »

Comments (9)

Showing 1-9 of 9

more from the author

-

Dust to Dust

The green burial movement looks to set down roots in Humboldt County

- Apr 11, 2024

-

Our Last Best Chance

- Apr 11, 2024

-

Judge Rules Arcata Can't Put Earth Flag on Top

- Apr 5, 2024

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023