Lazio's Last Stand

Eureka's waterfront started dying in 1968, and there's no good news on the horizon

By Meghannraye Sutton[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

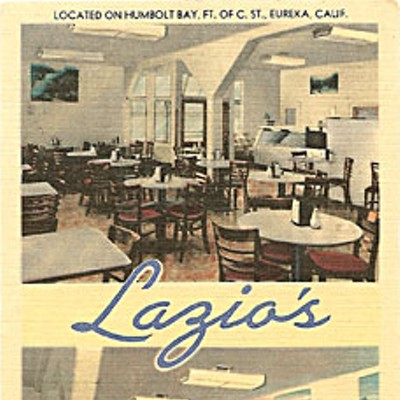

The year was 1968. The place was Eureka, Calif. Down near the waterfront on C Street, the finest fish cuisine and the most popular joint in town sat on the right on the pier, overlooking the bay full of sailboats and the skeleton of the nearly built Samoa Bridge. At the renowned Lazio’s Seafood Restaurant, locals and tourists sat at their tables as they ate seafood dinners and watched women in the kitchen working away behind plate glass windows. The smell of filleted fish wafted through the room, cut through the ominous buzz of conversation. People lined up out the door, halfway down the block just to eat there. This was the place to be. This was a bustling hometown business, the heart and soul of Old Town Eureka.

Go down to First Street today, and the waterfront is not exactly the most hopping place to be. Now it’s 2008, 40 years later. Many of the fishermen and loggers are long gone. Lazio’s Seafood Restaurant is long gone. There’s a six-year old boardwalk along the edge of the water that was christened in 2002, but not joined with any businesses until very recently. There are new vacant condos, and more than a couple vacant weed-infested lots. As it is now, our waterfront is not exactly what you would call the Santa Cruz Boardwalk or Monterey Bay.

The idea of waterfront development in Eureka is not new. On Aug. 6, 1971, a story was published in the Times-Standard with this headline: “Eureka’s New Waterfront Plan: Boat Basin, F St. Mall, Boardwalk.” Sound familiar?

Now it’s 26 years later, and “Eureka’s new waterfront plans” are finally manifesting themselves, painstakingly, piece by piece. Everyone -- big names, small names and everyone in between -- all have their ideas of what should go down on the waterfront. Condos. Parks. Home Depots and such. But developers say it’s not as simple as you think to just slap up a building, especially on prime, expensive property such as the Eureka waterfront.

^^^^^

Rewind time four decades. Lawrence Lazio was a pioneer, and a keen businessman in his day. Lazio was the first private property owner to try to put up a new enterprise right on the waterfront, when he tried to build Lazio’s No. 2. He ultimately failed. It’s one of the epic stories of his life.

In the ’60s, Lawrence Lazio was but a young buck. He was feeling pretty good about himself when he took over management responsibilities of the empire that his father, the late Tom Lazio, built from nothing. At only 20-something, Lawrence Lazio was a powerful man, a man of caliber and importance. He managed the family business and oversaw 350 employees -- basically ran the whole joint. In his spare time he attended what was then Humboldt College, eventually getting a degree in marketing. When he was one credit short of getting his diploma and was too busy with work to finish his college classes, the president of the college told him that it was all right, he’d give him his degree anyway. He had an important job to do, and that was to run Lazio’s.

Business was booming at Lazio’s Restaurant in the otherwise dead business district. Back then, there were no other restaurants down there. Lazio was swimming in customers. In order to serve the increasingly popular spot, Lazio thought he’d build a new restaurant to serve his clientele, tear the old one down and start new. Do it up big.

Lazio drove his car down to Bank of America in Henderson Center and applied for a $600,000 loan for the new place, which was immediately approved. With that money, he hired a highly regarded and very expensive architect from Los Angeles to draft the blueprint for his brainchild -- a new 15,000 square foot restaurant with a 140-seat dining room. Nothing too fancy, he said -- just comfortable, somewhere where people would want to eat, to visit. A destination restaurant.

In anticipation of the upcoming construction, he had his men start tearing down old coal shacks around the property to clear way for the new. To hype up the grand opening, Lazio submitted the layout of the new restaurant to the editor of the Times-Standard and they were splashed all over the front pages. This was big news in Eureka. This was the most popular restaurant in town wanting to grow, to expand. After the news broke, in June 1968, Lazio held press conferences to answer questions from local reporters and to hype up the publicity. This could’ve been the first real change on the waterfront since the Great Depression.

“It was the first proposed major change in quote 'modern times,'” he said last week, making the quote marks with his fingers. “It would’ve been a key development. It had the greatest chance of success as a historical foundation.”

One day, a couple weeks after the big announcement, Lazio attended a City Council meeting. When the meeting ended and Lazio was walking out the door to leave, then city attorney Mel Johnsen and a City Council member grabbed his arm. They told him to wait. Little did Lazio know, his big plans were about to get squashed.

“I had all these grand plans,” he said. "Then the city of Eureka came along and slapped them out of my hand.”

^^^^^

Lazio remembers that fateful day very well. He sat on a picnic bench last week outside of the V&N Burger Bar in Arcata, telling the tale of his life: Lazio’s Seafood Restaurant. The Burger Bar wasn’t his usual hangout -- now that he’s retired and has all the time in the world, he usually drinks coffee in Eureka every morning with the other geezers. He wore a baseball hat with a giant salmon embroidered on the front. Underneath was matted down but not completely gray hair. He spoke in a steady voice, an engaged and impassioned voice. Next week is his 71st birthday, he said. He’s an old man now, he said, but his mind is still sharp as a whistle. He remembers the day very, very well.

As he was walking out the door of that City Council meeting four decades ago the city attorney and the City Council member stopped Lazio and told him not to get too excited yet. “You’d better check out the title to your property,” they told him.

“What do you mean?” he said.

As it so happened, Lazio was not the only one with decision-making rights on his private waterfront property. The city of Eureka held something called a "cloud title" over his property, which meant that he couldn’t make any changes to his property without the city's permission. There was a complication over who owned the tideland, the waterfront area submerged during high tide. His new restaurant would go over the tideland area, and the city decided to contest the point and ultimately stop him from building the new Lazio’s. This complicated issue went back to a badly drawn waterfront property line from the 1800s, and now the city of Eureka was using it to prevent him from changing the waterfront without their consent.

So instead of being free to make changes to his own property, he had to sue the city of Eureka to clear the title. He eventually won the court case, along with all the other waterfront property owners who gained wind of the lawsuit and joined on his side. The waterfront land owners obtained clear titles to their properties in 1981. But when the case finally settled, Lazio didn’t get to build the 15,000 square foot restaurant. By the time he was done, he had put out $100,000 of his own money, and used up 13 years of his life. He wasn’t so young anymore.

“There was all kinds of whatever,” he said. “Hearing after hearing. Testimony after testimony.”

The dollar amount Lazio spent during the trial was only a portion of what the city of Eureka spent. The city spent $1.6 million in legal fees, which it borrowed from the state of California, trying to gain control of what could be a valuable -- the most valuable -- asset that the city had: the Eureka waterfront. And as it so happens, the city of Eureka is still paying on that loan today, for a court case that they ultimately lost.

Think: For the 13 years this particular court case languished in court, for the entire decade of the 1970s, all potential waterfront developments were put on hold. Many local old-timers blame this particular incident for delaying waterfront development and affecting our less than supple waterfront area today. What would have happened anyway, if Lazio succeeded in building his 15,000 square foot restaurant? What would our waterfront look like today?

^^^^^

Fellow fish-man Leroy Zerlang, impresario of the Madaket tour boat and an old friend of Lazios, was reached at work by phone last week. As Lazio’s name was mentioned his voice perked up and the volume went up a couple notches. He and “Lawry” are old buddies, go way back. By the time the conversation morphed into the topic of current waterfront development, Zerlang was practically spitting into the phone.

“It’s a dirty shame. It [Lazio’s] could’ve still been a booming business today,” he said. “Now [the waterfront] is city-controlled property by a bunch of idiots that are doing nothing with it.”

He continued on his impassioned rant. “He fought in court, spent tons of money. And look what happened. Nothing.”

“When it went out of business, it completely changed the atmosphere, the dynamics of Old Town,” he said. “It was the biggest staple in Old Town Eureka, and it still could have been. It was really alive. And now look at it. It’s dead.”

Even though the new Lazio’s was never built and the original one eventually burnt down in the ’90s, someone could have came in by now and built up something, right? What exactly is the holdup on the waterfront, anyway?

^^^^^

Last Wednesday, Greg Pierson sat at a conference table in his rustic, super-sized office overlooking Eureka, right down the street from the Eureka Mall, one of the properties he manages and his family owns. A silver flatscreen Philips TV hung above his mantle displaying pictures of his Bayfront One property, the first and only building on the Boardwalk. A poster with a 3-D rendering of a bigger, four-story complex hung on the back wall. Below it was a caption. “Bayfront Two.”

Despite all the stagnation on the waterfront, there has been one successful groundbreaker. If you’ve been down to the boardwalk, you’ve seen the very stout, modern-looking two-story Bayfront One building. It’s been completed -- twice now -- by developers Greg Pierson and Larry DeBeni. In 2005, if you were paying attention, you’ll remember how the building, right at the crescendo of completion, was built and went down in flames -- literally -- when a transient lit a bonfire inside.

“When it burnt down, Sharon [Pierson’s wife] and I went down there and just looked at each other, and said, ‘Wow, it’s going to be a busy day tomorrow’,” said Pierson. “But what can you do?”

Built up, burnt down, and then rebuilt again in 2006. Inside, there is now one store open, the first retail store ever on the new boardwalk. “Sea Breeze” is a stereotypical boardwalk store straight out of anywhere but Eureka. Piles of salt-water taffy and “Eureka, California” sweatshirts are for sale. The room smells sticky sweet of caramel corn. Behind the counter, employees wait to sell harbor cruises for the hordes of eager tourists with cameras -- tourists we are still waiting for.

Although Bayfront One is a privately owned endeavor, the city of Eureka does maintain some control of what goes on there through its zoning ordinance. It requires that the first floor of any boardwalk development be a retail store, or “commercial use.” Pierson said that for him this is a big problem. Candy stores and such aren’t the big money-makers, he said -- the million-dollar condos upstairs are.

It’s a catch-22. New business on the waterfront would help the local economy. Pierson envisions tables up and down the Boardwalk, tourists from all over the state packing the place, buying up ice cream cones and merchandise and pumping tons of money into the local economy. But it's difficult for developers to build there for a number of reasons. For one, there's the monstrous construction cost -- the land on Eureka's shore is not as stable as elsewhere. For another, these days banks don’t want to lend the money because of their own sketchy finances at this point in time, and because the Eureka waterfront is far from a tried and tested proposition.

But to hear a developer like Pierson tell it, the main hurdle is red tape -- not exactly the tape Lazio dealt with 40 years ago, but certainly of a kindred shade. Pierson said that every project he does, he has to jump through hoop after hoop, which takes years from the time the project was first dreamed up. He said about 40 different agencies have to approve every single aspect of the project. He said the big ones are the Eureka Redevelopment Agency and the California Coastal Commission, a state agency that oversees land use on the state's shores.

“People have no absolutely idea,” said Pierson. “They have no clue.”

This is what usually happens when he plans a project, according to Pierson: “Here is my project. Then people come along and say make it taller, make it smaller. You’re hurting the eelgrass. What about the footprint?”

The Bayfront One property, however, didn’t have to jump through quite as many hoops when Pierson bought it in 2001 from Rita Sicard, because the building was already fully permitted at that time. All he had to do was find the multi-million dollar financing to build it.

The personal money issue is also a biggie. Just to apply for a development permit costs about $25,000 -- of the developer's own money -- with no guarantee at all that he will win or lose. If he loses, he is out that money, and that’s that.

Well, someone like Greg Pierson can afford it, right? He’s a big honcho around town. He can just withdraw a few million from his bank account and build it up.

According to Pierson: No.

Pierson said it’s a common misconception that because of his last name he has all the money in the world to just throw in the wind. He referred to the Bayfront One property, at this point, as a “break-even deal.” Some of the multi-million dollar condos upstairs have sales pending, but none are actually sold at this point.

“I was lucky enough to be born into a well-known family. People know me. But that’s a myth. It was my grandfather who had the money.”

^^^^^

On the top deck of the Humboldt State University Library, there is a room of hidden treasures -- a pristine room, a silent room, a room for the educated. It’s called the Humboldt Room, a place of faded black-and-white photographs and volumes of local history. The 1,000-plus court exhibits from the Lazio vs. City of Eureka case, presented by the city during the epic 13-year court case, are now available for researchers and the public there.

And if you’re interested at all in learning about waterfront history, a display will be up on the first floor of the library for the rest of the summer. Back in 1984, someone from the city of Eureka decided they didn’t need that stuff anymore -- the court case had come and gone by then. After donation, the boxes sat in the trenches of the HSU library for almost 25 years -- until this year. It was during December that the exhibits were finally brought to light by two students, who incorporated the Eureka waterfront issue into their theses.

One of the students, Jacqualine Faria, wrote her thesis about the Eureka waterfront. She said that she didn’t know anything about this particular case when she first started examining the court exhibits in November. Now, after a year of tediously going through paper after paper, map after map, she is practically an expert on the Eureka waterfront.

Last week, she and group of archivists who work in the Humboldt Room stood in a circle. In front of them was an aerial map of Humboldt Bay, with a blue mark drawn across the waterfront line. The women talked about the tedious and painstaking process of putting a collection together.

How was that process, anyway? Was it fun? They just looked at each other and laughed. And laughed.

Faria said that she'd spend hours some days pouring through the various documents and trying to decipher what it all meant. She said she remembers when she first moved to Humboldt County in 2005 and saw the Bonnie Neely and Nancy Flemming television commercials promising to clean up the waterfront and wondering why it hadn’t been cleaned up and built upon yet. Places like Oakland already have a business district on their harbor, and for that city it wasn’t such a struggle. Now she understands how complicated it can all really be.

^^^^^

Sixty years ago is when Lawrence Lazio’s father, Tom Lazio, opened up Lazio’s Restaurant. Go to that property today, and there’s a fleet of yellow bulldozers leveling off gravel for the city’s new fishermen’s work area. After a few changes of hands, the old Lazio's restaurant ended up in the hands of his arch-nemesis: the city of Eureka.

City government has discussed the fisherman’s work area project for over 10 years now. In 2007, it finally obtained funding, via a $2 million loan from the California Infrastructure and Economic Development Bank. According to the city’s website, the money will be used to construct a market square, a fisherman's work building and cafe, and a 41-space off-street parking lot. The fisherman’s terminal, which is part of the work area, has already been built, and consists of four cranes on the dock in front of the property. After years, it’s breaking ground, but not everyone is so happy with the project.

In the eyes of Zerlang, who works right down the street, “It is a “friggin’ fake fisherman’s terminal that’s not worth the dynamite it’ll take to blow it up.” He says he feels the city of Eureka is “building just to build.”

Pierson commented that he thought the city of Eureka “goes ahead, constructs things without the consent of a lot of the fishermen down there.” Lazio concurred.

A few years ago, Lazio himself was one of the bidders for a fishermen’s café in the fishermen’s work area, at the site of his old restaurant. So was Pierson. The plan was to resurrect the old Lazio’s on the second floor of the building. Lazio said he changed his mind when what the city had in mind for the property wasn’t “exactly conducive to his personal vision.”

Although Lazio’s restaurant is long gone, the Lazio family tradition of making a living from the sea isn’t dead. His daughter and son-in-law now manage Pacific Coast Seafood, right down the way from his old place, which sits over the Eureka Waterfront.

Lazio said that even though the old Lazio’s Restaurant is dead, the businessman in him is not. Even though he’s past retirement, he still might consider a new endeavor if the right one came along. He still has his old menus and all the recipes, he said.

“Maybe if the right situation was on the table, I’d become active again,” he said. “I have grandkids coming up. Jobs are not easy to come by these days.” He has a mischievous sparkle in eyes as he speaks.

Zerlang says the city needs to sell the C Street property back to Lazio, that’s what they need to do. As the waterfront is now, it’s mostly city property, and the rest belongs to five or six big time developers who have grandiose plans. “Look at the crap they want to build there now,” said Zerlang. “They don’t want to build it unless it costs 50 million, is five acres and three stories tall.”

So what has come of this? In his many years on the bay, has Zerlang seen any worthwhile improvement or renovations? “Renovations?” said Zerlang. “I’m looking out into the bay right now, and I sure as hell don’t see any.”

Comments (13)

Showing 1-13 of 13

more from the author

-

Eureka's Top Toto

- Aug 7, 2008

-

Stop the Press

Durham puts McKinleyville's hometown paper on the block

- Jul 31, 2008

-

Something Out of Nothing

What to do with a boxful of gleaned goods from the food bank

- Jul 10, 2008

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023