Headwaters Forest at 10

In 1999, the public bought an irreplaceable treasure. And some problems. And some things we still don't understand.

By Heidi Walters[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Ten years ago, on March 1, 1999, the federal government and the state of California agreed to pay Charles Hurwitz of Maxxam Corp. $380 million for an imperfect and yet miraculous 7,472 acres of Pacific Lumber Co. land east of Humboldt Bay between Fortuna and Eureka. And all this coming summer, the Bureau of Land Management, which co-manages the reserve with the California Department of Fish and Game, will be hosting celebratory events to mark the 10th anniversary of the Headwaters Forest Reserve. There will be hikes, lectures, parties.

Some people, however, thinking back over the 10 years since the Headwaters Deal was struck that bought the public this forest, and remembering the dozen-plus strife-ridden and even bloodstained years preceding it, may be shaking their heads ironically at the thought of a celebration.

Granted, the deal gave the public the largest unlogged tract of old growth redwood forest in the world still in private hands -- and, later, two less-pristine old growth groves the state paid for with $100 million more. But the deal also wrested agreements from Hurwitz on how Pacific Lumber Co. would manage the rest of its 210,000-plus acres sustainably and to preserve protected species habitat, and to not log most of the old growth groves on its property for 50 years -- agreements which have generated much controversy and fostered numerous lawsuits since, with environmentalists saying they're flawed and Hurwitz saying they forced Pacific Lumber into the bankruptcy that eventually caused Maxxam to exit the scene last year.

But others may recall how the deal came within minutes of collapsing -- and who knows what would have happened to the Headwaters after that? U.S. Sen. Dianne Feinstein had managed to secure the Headwaters agreement in 1996, and Congress appropriated $250 million -- contingent upon California's putting up $130 million and the development of those agreements. The federal appropriation was set to expire at midnight March 1, 1999.

David Hayes -- President Barack Obama's designee for Deputy Secretary of the Department of the Interior, a position he also held in the Clinton Administration -- at the time of the deal was Counselor to then-Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt. Hayes was an integral player in the years-long negotiations for the deal. And a year after the deal became final, he wrote an edge-of-seater account of the dealmaking for the Environmental Law Reporter. Toward the end of the piece, he writes about the last few minutes before midnight, Pacific Coast time, just after Hurwitz -- who had given up on the deal in the last days -- had finally come around after some fancy footwork on Hayes' and others' part:

"Mass confusion. Documents were being sent to Eureka. Someone announced that the recording of the deal had begun. Two minutes later someone else announced that documents transferring title of the Headwaters Forest to the United States had been recorded. It was done! By the barest of margins. ... the Headwaters Forest now belonged to all citizens of the United States -- forever! And we had executed a precedent-setting HCP that established new standards for forest practices. ..."

The Headwaters belonged to the people. What did that mean, exactly?

[][][]

Well, it didn't mean that everyone got what they wanted -- certainly not the 60,000-acre Headwaters Forest that activists had mapped out. And the price was rather steep. But Byron Sher, who as a California state senator at the time was instrumental in shaping the Headwaters Deal to include better protections for the timberlands remaining in Pacific Lumber's hands, cautions against pondering the Headwaters Forest Reserve in isolation. The acquisition of that nearly 7,500 acres -- 3,000 acres of unlogged old growth forest in a cushion of 4,400 acres of heavily logged and roaded land -- plus two less-intact smaller groves elsewhere was the relatively simple part of the deal, he said.

"You bought that, and you also bought agreements from the company that they would log the land that remained in private ownership in a way that would complement the purchase of the reserve to make it a habitat for the endangered species," Sher said. "And those covenants run with the land."

That means the new owner, Humboldt Redwood Company, which took over after the bankruptcy, must follow the agreements.

Phil Detrich, a U.S.Fish and Wildlife Service biologist who was his agency's lead negotiator in the Headwaters Deal, said the deal also bought -- or so it was hoped -- something else that was critical. People were climbing into the trees and not coming down. And, two years before the deal was finalized, Sheriff's deputies had begun swabbing activists' eyes with pepper-spray-dipped Q-tips. Less than a year before the deal, a young man was crushed to death by a tree felled by an angry logger.

"It was increasingly getting violent, the conflict was escalating, and that was of concern especially to the politicians," said Detrich. "So, we bought some peace in the woods."

As it turned out, treesits, protests and legal challenges over logging and water quality issues and other things related to the deal continued long after it was sealed.

As for the main prize, the Headwaters Forest Reserve? Maybe "price" is the wrong way to look at it.

"It's what we got," said the BLM's new manager for the reserve, Chris Heppe, last Sunday on a rainy walk along one of the reserve's trails. "And it's invaluable when you think of the generations down the road. How do you put a value on clean water and carbon sequestration? On its ecological significance?"

[][][]

It was really obvious at the time, said activist Greg King last week, why the old growth redwood forest under Pacific Lumber Co. ownership needed saving. In late 1985, the company had been taken over by Charles Hurwitz's Maxxam Corp. And Hurwitz hired on a bunch of new hands, added shifts at the mill, and ramped up logging with a plan to maximize profits quickly (and never mind the company's massive debt, as its 2007 bankruptcy illustrated).

Pacific Lumber lands were already on forest conservationists' radar, as were lands owned by other timber companies, because the last of the old growth redwoods -- some that had been around for 2,000 years -- were being nibbled away. And now it seemed the last of them on Pacific Lumber land would vanish in a gulp.

"You know, 96 percent of the two million-acre redwood biome had been chopped down already ... and here we had the last of the last," King said. "And so when Maxxam took over Pacific Lumber, a whole bunch of bells went off throughout the country because people who watched old growth redwood and the protected status or lack thereof had been looking at these lands for a long time. And now they were basically watching it be cut down."

King said that at the time of Maxxam's takeover, Pacific Lumber held 8,000 acres of old growth and thousands more acres of residual old growth -- stands that had been logged selectively, leaving half the trees.

"And then what happened was, Maxxam came in and tripled the cut," said King.

The movement to stop Maxxam's liquidation of the redwoods took off, with groups like the direct-action Earth First! and the lawsuit-wielding EPIC -- the Environmental Protection Information Center, which uses environmental laws such as the Endangered Species Act and Forest Practices Act to file lawsuits to force protections -- expanding north, and new groups forming. EPIC had been challenging timber companies since the 1970s, first over herbicide spraying and then, by the early 1980s, over timber harvest plans, initially succeeding in saving an old growth grove in the Sinkyone, and later more on Pacific Lumber land, said Cecelia Lanman who worked with EPIC on the campaign.

"The first timber harvest plan we challenged [on Maxxam land] was in 1986 just after the takeover," Lanman said. "They had attempted to put a hole in the Headwaters Grove."

King, who was working as a journalist at the time, joined the fray. It was 1986, and he had just been offered the editor position at a Fort Bragg newsweekly. Before he started, he traveled north to see the Sally Bell Grove in the Sinkyone which activists were trying to save from being cut. He met activist Darryl Cherney -- Cherney and Judi Bari were soon to become lead organizers in the campaign to save old growth redwoods, and to get car-bombed in the process -- and he heard about what was happening on Pacific Lumber lands to the north.

"By February 1986 I was writing letters to CDF [California Department of Forestry] about timber harvest plans," he said.

In the fall of 1986, King hiked into a 1,000-acre Pacific Lumber old growth grove now called Owl Creek -- which ended up as part of the package of the Headwaters Deal, but not before Maxxam had cut 700 acres, said King.

"It was wildness, a place where people had never walked," he said. "I'd never experienced that feeling before. So I turned down the editor job the next day and moved north."

He and others began surveying and mapping groves, taking photos, writing letters, collecting data, researching timber harvest plans and more.

In March 1987, King and a fellow activist walked into the Headwaters Grove for the first time -- giving it its name when they saw the streams originating in there. King said he was the first to report a marbled murrelet sighting in the grove -- saw them flying in the high sky-spaces between treetops. Marbled murrelets, small seabirds that nest on the high limbs of old growth and make marathon forays to the ocean to catch fish, were known to be on the decline, and by 1992 would be listed as threatened under the federal Endangered Species Act.

Before that, in 1990, the northern spotted owl had been listed as threatened under the ESA. So there perched two more things to save -- although, as activist Ken Miller, along with others, likes to point out, the listing of those species should have been enough to prevent logging in the Headwaters. And if the forest had been appraised for its value under the constraints of the ESA, it would have come in as worth $20 million. "But Hurwitz said, 'I'm not doing that -- what's the value of the timber?'" Miller said. "And so it was appraised at $300 million."

And there was one more thing they were fighting to save, said Lanman.

"The aftermath of Maxxam certainly had a social impact: accelerating the cut and the big bubble of employment, and then all of a sudden there's no trees left to cut and people had to move on to other things," Lanman said. "And that was part and parcel why we were fighting -- not just for the old growth and marbled murrelets, but also for the legacy of what the Pacific Lumber Co. had left for Humboldt County."

[][][]

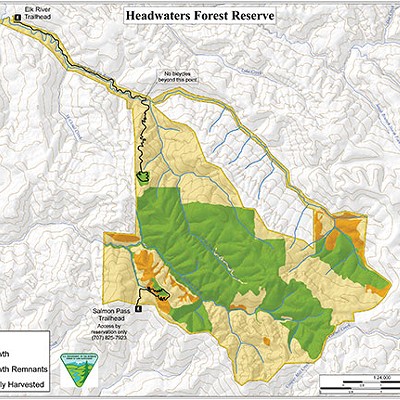

You can get into the Headwaters Forest Reserve two ways. You can take the Elk River Road out of Eureka to the trailhead at the north end and hike -- or bike, but only for the first three miles -- along the South Fork of the Elk River through thickets of maples and alders and younger redwoods and other trees, passing the site of the old logging town of Falk which the BLM has been sprucing up and a series of interpretive signs. After five miles, you come to a half-mile loop through a little patch of old growth forest that's disconnected from the main mass of ancients deeper in.

Or, you can go on a two-mile guided tour with the BLM, between spring and fall, on the Salmon Pass trail out of Fortuna, which also begins in previously logged land -- with its old road scars now being overtaken by thickets of thin young alders and planted redwood seedlings -- and ends in a small loop through a relatively small old growth stand also disconnected from the massive, intact interior stand. The trailhead is reached by crossing private timberland, hence the controlled access.

Beyond those two trails, the reserve is closed to protect sensitive species. You can't walk into the large old growth forest that defines the reserve. Bicycles are restricted to the three-mile portion of the Elk River Trail. And you can forget horseback riding in at all, anywhere. The limited access sticks in the craw of some people who thought they'd get more back when they were wrangling with the BLM and state Department of Fish and Game over their management plan, completed in 2004.

"We got screwed," said Dennis Mayo of McKinleyville. "We were told, oh, come on, join in and play in the fun. We were told that we were going to get horseback riding, we were going to get all this stuff to help with ecotourism. I don't think a trail for somebody to walk on and one damn bicycle riding trail is recreation. It certainly doesn't meet the needs of the horseback riding community. We got zero."

Mayo grew up in Humboldt County and, in his younger years, he'd go often into what's now the Headwaters Reserve -- back when it was private timberland still and was just referred to as "up in behind Falk" or "up in behind Boy Scout Camp."

"I had leased ranch land that bordered there many years back and sometimes my cows would get out and get down there and I'd have to go try to find them," Mayo said. "And then, you know, we'd go in there and go hunting. In those days, you just went. You didn't need permits. Although, let me tell you, there's a lot of places in there you can't access anyway. It's some pretty rough stuff in there. You know, you ain't gonna go horseback down in some of those holes, you'd never come out."

But there are places, he said, where a person could, say, take a group of people on an ecotour by horseback up onto the ridge that overlooks the main old growth grove, and then bring them back down to a meadow area to camp, all the while adding to the county's economy.

"How do we hurt the Headwaters by doing that?" he asks. "We don't."

Mayo "made it a mission to be madder than hell about the Headwaters." And, actually, he said the BLM's bent over backwards providing access since then on other lands in the region. And, he allows that he's glad for the wildlife's sake that the reserve is there.

Protecting and improving protected species habitat was, after all, the main charge in the legislation that created the reserve, with recreation a minor objective.

In her manager's report for 2008, the BLM's outgoing reserve manager Kathy Stangl, noted that, other than the northern spotted owls, the wildlife in the reserve was generally stable. She gave details: There were four pairs of spotted owls in the reserve and three pairs of barred owls -- that's the species that's been steadily moving West, displacing spotted owls. True, a new pair of spotted owls was found, although in marginally suitable habitat. But a new pair of barred owls had displaced a pair of spotteds. And another pair of barred owls had successfully raised young.

However, while walking along the Salmon Pass trail last Sunday on a special field trip, BLM wildlife biologist David Anthon said it's getting harder to count spotted owls across their range because the technique for surveying for them may have been compromised by the spread of barred owls. "Barred owls attack spotted owls when they hear them call," Anthon said. "So, there's evidence that spotted owls may have stopped calling."

Stangl's report also noted that marbled murrelets had been detected at an observation point where they'd not been seen before: perhaps an anomaly, or perhaps a sign of their looking for new places to nest.

The Headwaters Grove is vital to local populations of the marbled murrelet, Anthon said. "If you look at a map, the Headwaters Reserve is in an area where there isn't a lot of adjacent old growth," he said. "It's all been logged. You have to go north up into Redwood National and State Parks or south into Humboldt Redwood State Park, where you get into larger blocks of old growth redwoods and Doug fir."

He said it isn't known how many murrelets actually use the reserve, because they're difficult to detect in the forest other than to note their presence as they dart across the sky from canopy to canopy.

"The reliable census occurs out on the ocean [where they feed]," Anthon said. "We basically assume that any local birds are using the local nesting habitat, whether it be in the state and national parks or the Headwaters Reserve or other suitable habitat."

The BLM also monitors for birds in the Corvid family -- birds, like ravens, who like to eat murrelet eggs. In her report, Stangl noted the Corvids were getting up to their usual business along the Elk River Trail, which is pursuing scraps of food left by visiting humans.

While monitoring protected species is a main activity on the reserve, the most physical effort out there has been the watershed restoration work.

Back out on the trail last Sunday, reserve manager Heppe, and the reserve's ranger, Julie Clark, pointed out evidence of the work: dug-up logs and stumps scattered about that had once been used for roadbuilding -- often placed in streams and packed around with dirt to create crossings, back in the old days; old culvert pipes; thickets of skinny young trees growing in where the old roadbed had been recontoured to a more natural configuration; yet-unrestored, unstable sections of old road where a landslide could occur and dump tons of sediment into the streams.

The reserve contains the headwaters of two tributaries to Elk River, and all of the headwater streams for Salmon Creek. Sixty percent of the reserve was logged and roaded at some point between the 1880s and 1990s. Most of it had been clearcut, and some had been selectively cut with a scattering of old trees left behind. It was networked with about 60 miles of logging roads, some right near streams, said Heppe. The roads were accompanied by wide spots for piling logs, skid trails and more than a hundred dirt-and-log filled stream crossings -- all of which has induced at least 50 landslides, according to the management plan.

Mitch Farro, projects manager of the nonprofit Pacific Coast Fish, Wildlife and Wetlands Restoration Association, has been working with another group, Pacific Watershed Associates, on decommissioning roads and restoring the landscape both inside the preserve and on adjacent private timberlands owned by Green Diamond ever since the reserve was created. He said in a phone interview last week that they tackled roads in the Salmon Creek watershed first.

"We took out the Worm Road first," said Farro. "The environmentalists call it the Road of Death. It was punched right into the middle of the main grove in about 1996 -- it started at the top of the Salmon Creek watershed and went up the ridge and over the ridge into the Little South Fork watershed."

Heppe said the BLM has also been thinning out some of the Douglas firs on the reserve, where they've come in thickly on logged lands that once held old-growth redwood.

"We're trying to remove some of those to allow the redwoods to come back," he said.

In addition, the BLM also is studying and preserving the reserve's cultural resources -- from the site of the mining town of Falk, to older sites possibly once used by Native Americans, to the history of fire -- natural and human-caused. And it has been ramping up its education efforts, as well, with ranger Clark going into classrooms to talk about the reserve to kids, and taking people out into the reserve on hikes.

And if you just drive up to that Elk River Trailhead, park, and stroll a short ways, you can show yourself the recently reconstructed old train barn whose parts the BLM dragged across the river last year so they could set it up in a more accessible spot. Eventually, it will become an interpretive center and the site of outdoor classrooms.

[][][]

Many activists, and some biologists, say the reserve, though managed well, only goes so far to help protected species.

"Unfortunately, the Headwaters Deal took the charismatic Headwaters Forest, but it did not protect the whole watershed for salmon," said fisheries biologist Patrick Higgins, who serves on the board of the Humboldt Bay Harbor, Recreation and Conservation District. "And I counseled those decision makers at the time that this strategy of preserving this postage stamp and its geography would not obtain that objective, and it hasn't."

Higgins said most of the land in the Headwaters Forest, especially along the Little South Fork Elk River and the Salmon Creek watershed, is too steep for coho salmon, although steelhead and cutthroat trout fair somewhat better.

"It's really good amphibian habitat," he said. "There's probably a ton of tailed frogs and Torrent salamanders. The tailed frog is a species that breathes through its skin and can only live in water and air temperatures colder than 60 degrees, and it thrives in the microclimates of the Headwaters Forest."

He said the aquatic invertebrate community is also very diverse in the Headwaters, and the plant life.

But the fish need a broader approach.

"The rest of the area around the Headwaters has been highly fragmented -- there's extremely high road densities, there's very bad geology and the rate of timber harvest has been in the 80 percentile in Elk River since 1980," Higgins said. "Salmon are not thriving in Humboldt Bay nor in the lower Eel nor in the Van Duzen. We haven't done that well on private land, or even on protected park lands like Humboldt State Parks and the lower end of those tributaries that go across parks. So we don't have any coho salmon refugia."

Lynda Roush, field manager of the BLM's Arcata office, said her agency continues to forge partnerships with the landowners surrounding the Headwaters.

"We are looking at the headwaters of Salmon Creek through Green Diamond land [and other private properties], to the tidelands at the [Humboldt Bay National Wildlife] refuge," she said. "We're doing road restoration, Green Diamond's doing restoration. So it really is a landscape approach."

Greg King said he and other activists hope now that they can get other big landowners to do even more.

"Some real work needs to occur now to continue to link up these isolated islands of old growth, with real protected and restored habitat in between, in the Freshwater and Elk River drainages on Pacific Lumber lands," King said. "This is something a lot of us are hoping Humboldt Redwood Company will come to, is designing an interconnected habitat corridor from Humboldt Bay to the tops of the ridges out there. In order to recover the salmonid species, they really need that."

[][][]

So, you can't go in and see most of what's on the Headwaters Reserve. Its protected species are elusive. And the species we all have the most likelihood of coming into contact with, the salmon, isn't hugely benefited by it. Some people would say the whole deal set a bad precedent -- look at the Klamath deal, says Ken Miller, where once again the feds and state governors are promising taxpayers' money to stop a private corporation from doing what the law already says it can't do.

Maybe. But the Headwaters Forest represents more than the legal or political or even ecological battles surrounding it. It's more than its physical features. It is the symbol and embodiment of a time, and spirit, when a diversity of interests met with a great, clamoring, scary, exhilarating clash that reframed the conversation about ecosystems and working landscapes on the North Coast.

"What an incredible microcosm it was of the whole interaction between environmental laws and environmental philosophies and economic pursuits," said Phil Detrich, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologist who helped broker the deal. "You had environmentalists in trees and testifying in hearings. You had the forestry talent of the timber company. You had biocrats like myself. Biologists and attorneys and politicians. And it represented a true bipartisan effort to solve an environmental question. It was a Democratic administration in Washington, and we had U.S. Senator Dianne Feinstein. Then there was Republican Congressman Frank Riggs. And we had a Republican administration in Sacramento for the first part of the negotiations, with Gov. Pete Wilson, and then it concluded with Democratic Gov. Gray Davis.

"There was just a remarkable convergence of all of these interests around this special spot."

Detrich remembers one moment in particular that brought that home to him.

"In one of the public hearings on the draft habitat conservation plan, where people were limited to three minutes each, we had a long series of young and old environmentalists read The Lorax by Dr. Seuss -- you know, 'I speak for the trees,'" he said. "They read the entire book into the record as public comment. And that we, the biologists and scientists, had to consider these comments in the context of our dry reports -- it was a ludicrous concept. At the same time, it was one of the most moving moments of my life.

"And at the end, a crowd chanted "I speak for the trees. I speak for the trees. I speak for the trees.' It was just remarkable, to contrast that spiritual approach to nature with the laws and regulations and science -- to see the different paradigms of how we approach nature."

Comments (10)

Showing 1-10 of 10

more from the author

-

From the Journal Archives: When the Waters Rose in 1964

- Dec 26, 2019

-

Bigfoot Gets Real

- Feb 20, 2015

-

Danger at McCann

A kayaker's death has raised safety questions about low-water bridges

- Feb 19, 2015

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023