[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

The city of Trinidad is returning a $714,000 Caltrans grant after a contentious council meeting in which residents raised concerns that the trail renovation project it would fund might disturb a Native burial site.

"What is the cost of integrity and honor?" one of 20 or so public speakers at the Jan. 14 meeting said. "That is what is at stake here. The people affected have a right to say no. And we're saying, 'No.'"

Getting to the beach in Trinidad is not easy if you are a pedestrian or bicyclist. Edwards Street, a steep two-lane road with no sidewalk, is the only street accessing Trinidad State Beach, Trinidad Head, a restaurant, a commercial fishing pier, a boat launch and two other little beaches. The street's visibility is poor, blocked by a sharp turn about two-thirds of the way down the hill. Large trucks that serve the local fishing industry traverse the street, as do smaller trucks hauling boats.

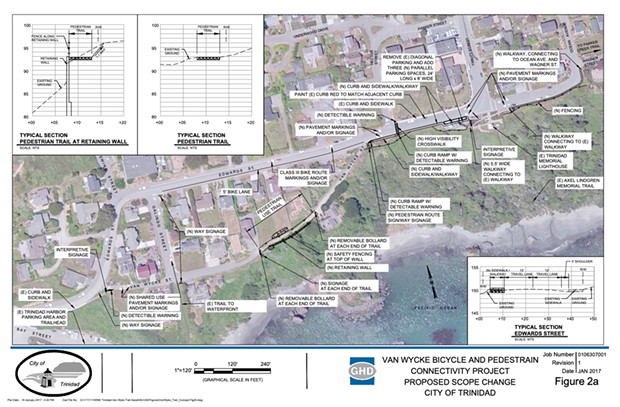

For decades, local pedestrians have used a small gravel trail to bypass Edwards. Known as the Van Wycke Trail, it skirts the steep bluff overlooking Trinidad Bay and is approximately 3-feet wide and also covers utility ducts, water pipelines and a storm drain. Most of the trail — which is accessed on each side by dead-end roads in residential areas — is on city-owned land.

The bluffs beneath the trail are under assault by the ocean waves and, as a result, the trail is geologically unstable. At present, it is difficult to pass due to a slide.

Several years ago, after a woman slipped on the gravel and injured herself, the city closed off the trail. However, many people ignore the "Closed" signs, preferring to take their chances on the trail than to walk Edwards Street. Besides pedestrians, the utility conduits and pipelines are also at risk and if the storm drain breaks because the trail continues to slide, water would drain across the open hillside, creating even worse erosion problems.

At one point, Steve Madrone, long before his election to the Humboldt County Board of Supervisors, was contracted by the city to build a wooden retaining wall along the bluffs and adjacent to the trail. Eventually that gave way, though, and the city began looking for more permanent solutions. That meant seeking grants. In 2016, Caltrans awarded the city a $714,000 grant that, in addition to stabilizing the trail, would add an 8-foot-wide paved bicycle lane, concrete sidewalks and curbs, "detectable warning surfaces" and split rail fencing, as well as a crosswalk, striping and directional and interpretive signs on the adjacent roads.

To hold the trail in place, project planners proposed building a retaining wall on its ocean side. The wall would be anchored by pilings hammered 19 feet into bedrock.

Many Trinidad residents, as well as the California Coastal Commission, have questioned how a simple trail repair evolved into a major street re-building project, which some feel would change the appearance of the village for the worse.

But the greater issue that emerged is the possible presence of human remains on the project site, which could be disturbed by the renovation.

The issue is literally centuries old. The Tsurai people, who are culturally related to the Yurok Tribe, lived in the area that is now called Trinidad for centuries. They were evicted by white settlers but one particular family, the Lindgrens, made a point of trying to protect the graves of ancestors buried nearby from grave robbers and looters. After years of negotiations, a settlement was finally reached in 2005 that protected 10-acre plot of ancestral land, called the Tsurai Management Area, on a former Tsurai village site, near what is now called Old Home Beach. A trail to the low-lying forested area was built down from the bluff on Edwards Street and a few benches were installed.

The area was supposed to be managed and improved by a consortium of government agencies and tribal groups, including the Lindgren family, which had created a nonprofit organization called the Tsurai Ancestral Society. But things never seemed to move forward and, eventually, the issue ended up in court. Anger again flared nine years ago when a neighboring homeowner illicitly cut trees in the management zone, allegedly to improve their ocean view.

Another flare-up happened last year, when the iconic replica of the Trinidad lighthouse needed to be moved because it was in danger of sliding down the bluff. Many Native residents worried that stabilizing the bluff could endanger the management area and its grave sites below. Days of protests and picketing followed until the lighthouse was eventually transported to an inconspicuous location near the beach.

Now the Tsurai people fear boring deep holes into the earth will disturb other unknown burial sites that may exist outside of the Tsurai Management Area, especially along Edwards Street, which is directly above the old village site.

This concern should not have been news to the Trinidad city government. The project's Mitigated Negative Declaration, an environmental document required by state law, states quite clearly that the potential exists to find cultural artifacts and even human remains on the project site. Nonetheless, the town planner stated that, with mitigations, this was unlikely to happen.

But the Tsurai Ancestral Society and the Yurok Tribe were not buying this. After sending a detailed letter to the city objecting to the project, about 20 Native people and their allies showed up at the Jan. 14 Trinidad City Council meeting to demand that the project be halted.

First to speak was tribal elder Axel Lindgren III. The audience, council and staff watched in absolute silence as Lindgren, supported by a walker and a family member, slowly and precariously moved to the podium. He then spent 10 minutes berating the council for not having lived up to its previous promises to protect grave sites, improve the trail to the old village site and remove cell towers from Trinidad Head, which he said had been a sacred spot "since the beginning of time."

Other speakers, including some from the local branch of the NAACP, continued expressing their anger about what they considered the city's malfeasance, although some non-locals seemed a bit confused about the distinction between Yurok, Tsurai and Wiyot people, with one woman comparing the current city council to the white settlers who had conducted the infamous massacre on Tuluwat Island.

An ancestral society member reminded the council that the city is currently suing the group over issues related to the management area.

After addressing other city business, including a presentation on climate change by students from the Northcoast Preparatory Academy, the council returned to the Van Wycke Trail issue. More members of the audience criticized the city, saying the concerns of Native people had not been adequately addressed.

Audience members also accused the city of violating the Ralph M. Brown Act — California's open meeting laws — and failing to hold state-mandated government-to-government meetings, allegations that city staff denied.

Tsurai Ancestral Society Secretary Sarah Lindgren said the city had been changing the maps and parameters of the project for years and it was difficult to know just what was being proposed. She said the Van Wycke Trail closure had already been promised in an agreement dating back to 2000, when other improvements were made to Edwards Street. City staff, however, said they had no records or memory of such an agreement.

Madrone, speaking from the audience, said the project could endanger ancient graves and that no drilling should occur on the bluff. He noted the ocean was going to continue to threaten the bluff whether a retaining wall was built or not, and urged staff to meet with the tribes to come up with a better project.

By this point, the council was clearly convinced it had a problem but there was the question of whether the $714,000 Caltrans grant would have to be returned.

After further discussion, the council passed a vaguely worded motion that abandoned all work on the Van Wycke Trail project, which means the $714,000 grant can not be claimed and leaves the city to pay for thousands of dollars of preliminary project studies and environmental analysis already conducted.

The sole dissenter in the vote was Councilmember Dwight Miller, who wanted more time to study the issues.

Despite the vote, council members indicated they still hope the city can work with Caltrans to find an alternative use for the money, perhaps by finding a different means for pedestrians to access the beach and re-locating the buried utility lines.

— Elaine Weinreb is a freelance journalist and prefers she/her pronouns. She tries to repay the state of California for giving her a degree in environmental studies and planning (Sonoma State University) at a time when tuition was still affordable.

Speaking of...

-

Harbor District to Talk Labor Agreement Amid Request for Delay

Aug 8, 2023 -

UPDATE: 101 in Mendo Reopens

Mar 28, 2023 -

Reminder: Fernbridge Hard Closure Begins Friday Night

Mar 16, 2023 - More »

more from the author

-

Trouble on the Mountain

A popular outdoor recreation area is also a makeshift shooting range, causing growing safety concerns

- Jan 11, 2024

-

Port of Entry

Harbor District begins environmental review for project to turn Humboldt Bay into a wind farm manufacturing hub

- Jul 27, 2023

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023