Epic Scrolls and Journeys

Laura Corsiglia and Lida Penkova at the Morris Graves Museum of Art

By Gabrielle Gopinath[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

To stand in the middle of the building that houses the Morris Graves Museum of Art and look up is to feel the pull of the former Carnegie library's Renaissance-derived architectural language. An octagonal array of veneered and polished redwood columns rise two stories to frame the view into the dome. The space is split into an upper and a lower realm. Like all domed interiors, it implies an inaccessible beyond. It's a form with a built-in way of seeing the world.

This week the symmetry of that view is rent by a banner-like painting on vellum that swoops down from the second floor, slicing the building's midline with a diagonal swoosh like the sign of Zorro. Laura Corsiglia's 42-foot-long "Plunge Dive" cuts against the grain of all the upwardly oriented forms surrounding it.

Corsiglia has worked with scrolls before, drawn perhaps to the medium's ungainliness. Resistance to a frame is intrinsic to a scroll. Scrolls are like epics in the sense that they can go on forever or at least until the physical support runs out. There's always another feat of derring-do ahead for fictional heroes (sequel alert!) and nothing but death can still the twisting leaps of the inner monologue — we'd know this from experience, even if Modernists like James Joyce and Virginia Woolf hadn't reminded us. A scroll has few fixed boundaries. It can be like a magic carpet that slides out from under or above the bounded picture plane, evading its X and Y axes. Many pioneers of video art simply performed until the videotape or filmstrip's recording capacity had been met; Corsiglia does something like that here, inscribing vignettes until the scroll runs out.

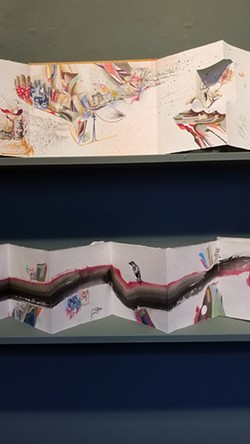

Wordless books on display are another species of open-ended form: paintings on long strips of paper folded like accordions or double-breasted envelopes. Multimedia paintings are brushed, colored and inscribed with figures, portraits, contour drawings and geometric patterns. These passages jostle together in the same pictorial space, though their orientation, implied perspective and scale range widely.

The bilingual artist, a British Columbia native who earned an MFA at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris, France, describes her approach with the phrase "de fil en aiguille" or "from the needle to the thread," a rhyming French idiom for a process where each step is progressively derived from the one that came before. Here it's the title of a painting featuring fragments of landscape that segue into polygons, tiny vehement figures and assorted vivid stains, each image evolving from its predecessor.

Multiple orientations and shifting vantage points, a picture plane that evades frames — these gambits conjure a world where observation is understood as an act of exchange. "When you look into the abyss, the abyss also looks into you," as the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche said. Corsiglia rehabilitates wildlife professionally when she is not making art (she is co-author of a practical guide to waterfowl rehabilitation) and her paintings make the case that this principle of reciprocity holds equally with pelicans, swallows and other living objects of the gaze.

On the museum's first floor, paintings and prints by Lida Penkova celebrate rituals that are social and collective. This self-taught artist depicts traditional rites and cultural practices from Mexico, Puerto Rico, Ireland, Australia, and other places she has lived or visited in a style she describes as naïve. Strong contour lines are filled in with cells of brilliant color. Figures stack on top of one another in disregard of linear perspective. Canvases and hand-painted linocuts are packed with action, while the painted driftwood sculptures that the artist creates with her husband, Daniel Doherty, communicate movement — they seem to have been arrested in mid-dance.

Penkova is fascinated by the premodern cultural forms that advanced capitalist society has pushed to the margins around the world. Her art celebrates the rituals these cultures created to foster community and access the divine. She describes herself as uninterested in most forms of modern art except Surrealism. "What inspires me are indigenous cultures and self-taught artists," she says Her life has encompassed more than the usual share of modern dislocation. Born in the Czech Republic, a country that no longer exists, Penkova lived in France and Germany, became a psychologist and practiced for 16 years in Tepoztlán, a town in rural Mexico reputed to be the birthplace of Quetzalcoatl, the Aztec feathered-serpent god. Her process draws on the reservoir of memories she created through living in this indigenous village and studying for years with an indigenous shaman.

"If I decide I want to paint, say, a wedding ceremony in Mexico, first I sleep on it. I start to remember what I've seen and then it composes itself. I suppose there is thinking involved but intuition is much more powerful," she says.

Every work of art takes shape within the limit conditions of its historical moment and the modern nature of these works is apparent in the way representational details differ slightly from one body of work to the next, as if selected from a drop-down menu. A painting of chinelos, traditional dancers from the Mexican state of Morelos, is rendered in a style that recalls folk art retablo paintings, while a series inspired by the paintings of indigenous Australian artists enacts aspects of their representational tradition, placing hybrid human-animal figures defined by broken lines against pale backgrounds.

The small, brightly colored, intricately patterned panels staggered around the gallery perimeter are like framed vistas onto mythic worlds. "Everything I paint has to do with my experience and my life: the cultures I've lived in, their customs and my participation in these traditional practices," the artist said. "I never wanted to be a tourist. I went to Mexico or to Puerto Rico or Nepal because I wanted to experience these cultures and take part in them."

Speaking of...

-

Music Today: Sunday, Feb. 18

Feb 18, 2024 -

Full Circle Journey

Oct 26, 2023 -

Truth Units

Sep 7, 2023 - More »

more from the author

-

Nancy Tobin's CRy-Baby Installation at CR

- Feb 22, 2024

-

Truth Units

Bachrun LoMele's Burn Pile/The Andromeda Mirage at the Morris Graves

- Sep 7, 2023

-

Ruth Arietta's Illusory Interiors at Morris Graves Museum of Art

- Aug 10, 2023

- More »