Drunk in Public

The challenge and tragedy of policing a public health crisis

By Linda Stansberry [email protected] @lcstansberry[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

In the long, hot month of August, as ash fell from the sky, the sun and moon did a brief astronomical dance and the public's attention darted from national tragedies like Charlottesville and local dramas like the arson and razing of Eureka's Blue Heron Motel, law enforcement officers in Humboldt County quietly continued to work on the front lines of one of our most pressing, resource-intensive and misunderstood public health issues: public intoxication.

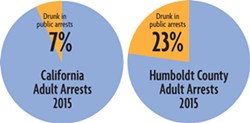

One-fifth of all people booked into the Humboldt County jail last month were arrested under penal code 647f, California's public intoxication statute. August is not an anomaly — of all arrests made by all local law enforcement agencies in 2017, 21 percent were drunk in public arrests. Almost one-quarter of all arrests in 2016 — 24.1 percent — were 647fs. And in 2015 — the last year for which statistics are available through the California Attorney General's Office — we arrested people for public intoxication at a rate of more than three times the state average. In fact, in 2015, Humboldt County accounted for 3 percent of the state's public intoxication arrests despite having just 0.4 percent of its population.

"This is hands down the highest volume of arrests we make," says Arcata Police Chief Tom Chapman, whose agency has made 355 arrests for public intoxication so far this year. "Second highest is for warrants, then [driving under the influence]."

What are Chapman's officers doing when they could be finding felons or preventing hit and runs? They're dealing with people too intoxicated to take care of themselves — the guy you see walking down the middle of the street yelling at the air, or the woman slumped against the side of a building. They're detaining people, driving them to the county jail, filling out paperwork, cleaning vomit out of the back of their squad cars and often waiting hours in hospital emergency rooms for the arrestees to be medically cleared.

Despite the common name for the law, it is not actually illegal to be drunk in public. To qualify for arrest and detention, people must be so intoxicated that they present a threat to their own safety or the safety or others, or be obstructing use of a street, sidewalk or other public way. The majority of public intoxication arrests appear to be for people on the streets who are chronic alcoholics and addicts. Of the 182 August arrests the Journal analyzed, almost exactly one-third — 56 — were of repeat offenders, a handful of people arrested twice or more in the same month for public intoxication. Some officers call them "frequent flyers," others "chronic inebriates." A medical professional or addiction counselor might diagnose them as alcoholics or addicts, people who continue to drink or use despite repeated negative consequences, often due to a physical dependency on their drug of choice. Unable or unwilling to access treatment options (of which there are too few in Humboldt, see "Can Humboldt County Solve Addiction?" Sept. 14, 2015) police are often the only intervention available for some of the most desperate members of our community. And many people, officers included, find this an inadequate response to what some have called a "crisis."

"Arrests for public intoxication consume a significant amount of time for our police officers," says Chapman. "It is directly related to the chronic public intoxication. The majority of those we're talking about aren't somebody that got too drunk on their 21st birthday, that's more the exception than the rule. The normal is the chronic inebriate, cycling through over and over and over again."

Twenty-two different people make up the 56 repeat-offender arrests. Several names appear on this list between three and five times, picked up by officers on an almost weekly basis. Occasionally they have additional charges, such as probation violations or trespassing. Many have a long and tangled history of contacts with law enforcement and social services. There's the 48-year old Eureka native, one of the first people sheltered through the Arcata Bay Crossing housing project, who has been arrested 11 times in the last four months for public intoxication. A 45-year-old man with a long rap sheet in Oregon, who was released from jail in Eugene last February after serving a brief sentence for aggressive panhandling and spitting on an officer, turned up in Arcata at the end of August and was arrested four times within one week, after trespassing near the bus stop and shoplifting from a local grocery store. EPD picked up a 39-year-old woman, who bounced from being homeless in Oakland into a treatment program in Eureka, three times in August.

The charges do not always match the reason for initial contact, such as the Oregon man arrested for shoplifting. But with storeowners or bystanders often unwilling to pursue charges for small offenses, 647fs make a useful tool for officers to get people causing a disturbance off the street for some period of time — long enough for them to sober up and/or calm down before being released. While the misdemeanor offense carries a potential sentence of six months in jail and a $1,000 fine, the chances of an arrestee actually going to court are small.

The burden of proof for an officer to arrest someone on a public intoxication charge is low, requiring only that they display symptoms of intoxication, such as slurred speech or bloodshot eyes, and that they pose a danger to themselves or others. Breathalyzer tests are neither required nor customary for drunk in public charges. Unlike driving under the influence, which requires an objectively-measured level of intoxication, the criteria under which an officer can arrest someone for public intoxication is more subjective, accounting for the various ways different people respond to alcohol and other substances.

"Normally we don't do breathalyzers because there's no set standard," says EPD interim Chief Steve Watson, adding he doesn't believe that officers overuse the statute.

Watson says officers try to minimize subjectivity but even seasoned professionals make mistakes. (He himself contacted a man on July 19 who was slumped against a building on Second Street, sending him to jail for public intoxication only to later find out the symptoms were due to a neurological disorder.) But while the burden of proof is very low, the incentive for officers to misuse or abuse the statute is equally low, the chief argues.

"Remember, this is a very low level crime," Watson says. EPD has made more than 750 arrests that include 647f charges just in 2017. Very few of those — likely only the ones that include other charges, such as parole violations — will actually see court time.

The district attorney's office estimates that in the 500 to 700 case referrals for 647fs it sees each year, it files charges on fewer than half.

Watson says the majority of the drunk in public arrests his officers take include an 849(b) designation by an officer, meaning the person arrested will be booked in until they sober up, then released without a request for criminal charges.

"It's more of a community caretaking function," Watson says. "It's a constant, daily problem."

Kevin Robinson, the county's former public defender, sees it differently. People who aren't technically intoxicated, but who might be having a mental health crisis or disturbing the peace, are arrested "all the time," he says.

"Clearly, it's somebody you don't want to leave on the streets," Robinson says. "You can evaluate someone while you detain them. You can deal with the crisis."

And while few 647f arrests result in charges, every arrest, he says, has a cumulative effect. If a police officer runs your name and pulls up a long rap sheet, he or she is going to treat you differently. A misdemeanor charge, especially one involving controlled substances, can impact a person's financial aid, food stamps or immigration status. And the odd person who wants his or her day in court — the college student booked after passing out on the Arcata Plaza and is now facing the loss of a scholarship — has few legal mechanisms to work with.

"As a public defender, you want them to fight it," Robinson says.

But the idea of spending hours in court for a trial, and possibly losing your job or missing class, makes the decision for most people — they take the offer from the district attorney's office, plead guilty and add a misdemeanor charge to their records.

While most of these arrests never make it to the courtroom, they take up hundreds of hours and thousands of dollars in public services. The average arrest takes an officer off the streets for an hour to 90 minutes, more if the jail's staff requires a suspect to be medically cleared at the hospital.

Once at the jail, the medical staff might check the vital signs of an arrestee, determine his pulse is too fast, his pupils too enlarged, or the tell-tale signs of physical withdrawal from alcohol — the shakes, hallucinations, the occasional seizure — are about to kick in, and decide he needs some extra care. That sends the person and the accompanying officer to the hospital emergency room for care and monitoring, a process Chapman says can take four to six hours.

But even excluding hospital visits, Eureka poured as many as 1,125 patrol officer hours into making drunk in public arrests through the first eight months of this year at a cost of roughly $29,800, according to the Journal's calculations.

For Watson, the impact of addiction and alcoholism on emergency services was brought home in a personal way two years ago when his mother needed to go to the emergency room. His family waited for hours to get her care; many of the rooms that night, the chief found, were taken up by chronic inebriates and people suffering the side effects of drug abuse. They had to make his mother as comfortable as possible in a waiting room chair and treated her sitting up rather than in a hospital bed.

"I have the utmost respect for people who work in emergency care," says Watson. "They just didn't have the space. When you have a loved one who can't get proper care, you start thinking about these problems in more depth."

Compounding the issue of a bottleneck in emergency services, Watson says that occasionally his officers will take someone to the hospital for clearance, clear them, and then have them rejected again by the jail's medical staff. He says he finds this phenomenon frustrating.

Duane Christian, staff lieutenant at the jail, says this happens because the hospital might have a misconception about what his facility can offer in terms of medical care.

"We have contracted medical through (California Forensic Medical Group)," he told the Journal in an email. "They have certain thresholds for acceptance of inmates when it comes to blood pressure, pulse, blood sugar (if diabetic), etc. ... In a lot of cases somebody is refused with, say, a pulse of 150 (which is extremely high) and then when they come back from the hospital it is lower (like 140 or 130) but still above the threshold CFMG is comfortable accepting them. ... A hospital would have no problem managing a patient with a pulse of 140 or 130 but CFMG does not have emergency equipment such as a crash cart [at the jail]. They give basic medical care and anything beyond that is done at the hospital."

Watson also believes that many people from surrounding communities who are struggling with mental health and addiction issues wash up in Eureka as they cycle through the jail or county mental health, ultimately landing on EPD's plate.

"I have a belief that Eureka is a dumping ground for many problem individuals from outlying communities," he says. "When someone is released, they're not released back to their county or town of origin. They're given bus tickets but that's not enough."

In some cases, a person transported to the hospital by ambulance will not be escorted by their arresting officer, which means that when they're ready to be released to the jail, hospital staff will call the nearest law enforcement agency to transport the arrestee, usually the Eureka Police Department. Watson says this is one of many problems he's gathering stakeholders to address.

For his part, Chapman says this has been a long-standing bone of contention and affects his officers as well, to a lesser degree, when Humboldt County Sheriff's Office deputies bring someone in from outlying communities and drop him or her off at Mad River Community Hospital, leaving APD to transport. In addition to the hospital discharges, there are people having mental health crises who ask to be transported to Sempervirens. Sometimes, he says, they change their minds and decide not to go inside. Officers can't force someone to accept mental health care except in extreme cases, meaning he or she will instead wander off into the streets of Eureka.

"This has been going on forever," he says. "But it's not a dump and run. It's really where we need to have a harder conversation."

Eureka City Councilmember Kim Bergel, who did a ride-along with a Eureka police officer shortly before taking office in 2014, says the experience of spending four hours at the St. Joseph Hospital emergency room with a man picked up for public intoxication underscored how pressing this issue is and inspired her now three-year long attempt to create a sobering center in Eureka.

Sobering centers, established or in the works in cities as large as San Diego and as small as Klamath Falls, are generally cheaper, less punitive versions of the jail's drunk tank. Provided people aren't violent or in immediate medical distress, officers can bring them there, sign them in and leave them to be monitored by the center's staff, who check on them every 15 minutes as they sleep it off. The size, scale and organization of such facilities vary. In San Diego, the center is a large warehouse with easy-to-clean sleeping mats. Klamath Falls' center, currently under construction, will have eight separate rooms that can be locked and staffed by two treatment professionals.

Dave Henslee, chief of police for Klamath Falls, says he is looking forward to seeing the sobering center come to fruition in 2018. Klamath Falls has roughly the same population as Eureka and Henslee says after he took office he noticed a similar bottleneck of resources due to public intoxication.

"Our holding cell was filled up with people just sleeping," he says. "Most were habitual offenders. We had just 20 people that owed the city $28,000 in fines."

Tom Gilbert, CEO of Klamath Basin Behavioral Health, which is overseeing the sobering center project, says the program has been in the works for more than 10 years and affected agencies are anticipating a substantial savings for taxpayers.

"Typically, sobering in the hospital emergency department will run thousands of dollars," he says. "People can sober in jail but the jails don't really cherish doing this. They tie up jail space, they vomit, soil themselves. Other things can happen — they can be victimized more easily."

Sobering centers, especially when staffed by addiction counselors, can also offer a more therapeutic environment for alcoholics and addicts. Some have onsite counseling and access to treatment resources. Bergel's initial vision for a Eureka center included a built-in incentive to push people toward help — after a person had been admitted to the center three times, he or she would have an option to either going into treatment or spending a definitive length of time in jail, but overcrowding in the Humboldt County correctional facility means this might not come to pass. On Aug. 1, the state denied the Humboldt County Sheriff's Office's application for a $17 million grant to add a 52-bed mental health treatment wing to the jail, putting a crimp in Bergel's plans. She and other stakeholders have also met with John McManus of Alcohol Drug Care Services, which is gearing up to offer a detox and residential treatment program at the building formerly known as the Multiple Assistance Center, now Waterfront Recovery Services. McManus, who did not return Journal emails for an interview, reportedly expressed interest in adding a sobering center at a later date.

In the meantime, Bergel is resolute. She believes a sobering center like the one set up in a San Diego warehouse that she, Councilmember Heidi Messner and EPD project coordinator Lynette Mullen visited in July, would be easy to implement with relatively low overhead.

"You just need a warehouse, some mats, buckets, towels and bleach," she says. "After four hours, they can sign themselves out."

Other details, such as whether the staff on hand would be trained medical experts and whether there would be a risk of liability for the city, are still nebulous. What is clear, as amply evidenced by the recent federal verdict in favor of the family of Daren Borges, who died in a Humboldt County jail sobering cell after overdosing on methamphetamines, is that people do die from public intoxication. They die in sobering cells, they die on the streets and they die after being taken to the hospital by officers, as was the case with Jeremy Jenkins, who in April of 2016 died shortly after being admitted to St. Joseph Hospital for "acute methamphetamine intoxication."

"We're dealing with people that, by virtue of their substance use disorders, are also dealing with a host of medical issues," says Gilbert, adding he's done "a lot of homework" on the liability issues. "It's work to be taken very seriously."

Support for the center seems universal — former EPD Chief Andrew Mills, Open Door Community Health Centers CEO Herrmann Spetzler and chiefs Watson and Chapman all voiced their enthusiasm. Many believe it will lessen the resource-intensive issue of policing public intoxication. But it can't solve everything. Local hospitals, for example, will continue to serve those with problems that can't be cured by sleeping it off. Human error and the freak nature of major health events cannot completely be eradicated — as well trained as a center's staff may be, people might still die under their watch. And a soft place to sleep can't cure alcoholism or addiction.

Daryl Durham, an Arcata resident who has been picked up for drunk in public charges a total of 12 times by Chapman's officers, says he's mostly grateful for the encounters he's had with the police.

"I can say there's good cops and there's bad cops," he says. "But they have scraped me off the streets when I couldn't take care of myself and I appreciate it."

Durham, whose last arrest was on Aug. 24, says he doesn't always feel safe in jail. The drunk tank — just a bunch of chairs in front of a television — is OK, but when they put him in a private cell he was worried.

"You kind of feel like you might get forgotten about," he says. He adds that if treatment were offered in lieu of jail time, most people would go for it.

"A lot of times, the system is set up so they arrest most of the local drunks and they don't get charged for it," he says. "They let them out at 5:45 a.m. right when the liquor store opens."

When the jail releases people in the early morning hours, the closest place that sells liquor is the Patriot Gas Station, he says, close to the Samoa Bridge. It opens at 6 a.m.

Linda Stansberry is a staff writer for the Journal. Reach her at 442-1400, extension 317, or [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter @LCStansberry.

Speaking of...

more from the author

-

Lobster Girl Finds the Beat

- Nov 9, 2023

-

Tales from the CryptTok

- Oct 26, 2023

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023