[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

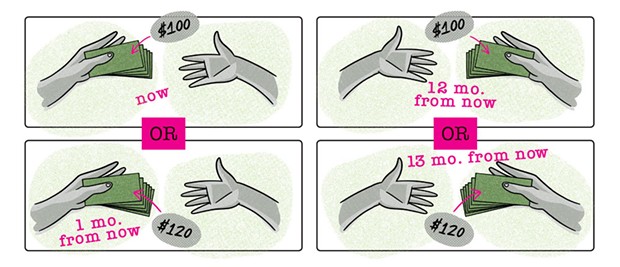

Quick quiz: Would you rather receive $100 right now or $120 a month from now?

Most people take the $100 right now, despite the extraordinary offer of 20 percent per month interest. Let's do that again. Would you take $100 a year from now or $120 13 months from now? Most people choose $120, even though the payoffs are identical — we tend to compress time according to how far it is from the present.

This is called present bias, one of nearly 200 (you can peruse a list on Wikipedia) innate cognitive biases that have been uncovered by researchers. Present bias is what makes saving for retirement so difficult: We'd rather spend the money on ourselves today than, in effect, give it to a "stranger" years from now.

Another bias, with profound and disastrous consequences, is the sunk-cost fallacy. When President Trump announced in 2017 he was ordering more troops to Afghanistan on the basis of "the tremendous sacrifices that have been made, especially the sacrifices of lives," he was echoing George Bush's 2006 rational for staying in Iraq: "I'm not going to allow the sacrifice of 2,527 troops who have died in Iraq to be in vain, by pulling out before the job is done." In both cases, of course, the justification is bull patties.

The sunk-cost fallacy is what keeps us hanging on to worthless shares, staying in an unhappy marriage (in which you've "invested" years of your life) or not quitting the job we hate (after all those years of college). See "Physics' Beautiful Crisis," Dec. 6, 2018, for how physicists may be similarly deluded into following unproductive research.

I'm a huge fan — that is, I'm consistently deluded by — the actor-observer bias. This is where we judge others' behavior by overemphasizing the influence of personality and underestimating the influence of their situation. ("If she just put her mind to it, she'd lose weight," rather than "No wonder she eats junk food — she doesn't have the time or money to eat healthily, given her family situation.") Meanwhile, when judging our own actions, we tend to attribute our bad choices to the situation ("I was blinded by the sun in my eyes"), not our personality ("I was being an idiot driving so fast") — the opposite of how we judge others.

If you were persuaded in February of 2015 when James Inhofe of Oklahoma, then chairman of the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee, brought a snowball onto the Senate floor to "disprove" global warming, you were indulging in base rate neglect, the fallacy of glomming onto individual examples and anecdotes more than statistics. (In this case, statistics accepted by over 98 percent of climate scientists showing that the planet has warmed by 1.5 degrees Fahrenheit on average since the start of the Industrial Revolution, mirroring atmospheric carbon dioxide levels.)

Hmm. This column seems to be taking longer than I imagined. Could that be anything to do with my optimism bias, in which I (that is, we) underestimate cost and time of every project undertaken?

The interesting thing is just why we're saddled with all these cognitive biases. Turns out, they probably worked to our advantage millions of years ago on the African savannah, when our brain circuits were being formed. Present bias, for instance: Who knew if you were going to be around next month, given the high mortality rate during the Pleistocene? It's a fun exercise to follow through with some of the other common biases, to see how they might have served us back then, when survival was so hit and miss. Unfortunately, we're still stuck with them.

Barry Evans ([email protected]) wonders how someone who believes they're not deluded could check?

Speaking of...

-

New Police Accountability Laws Up Demands on State Agencies

Jul 27, 2022 -

Police and Prison Guard Misconduct and Bias: Audit Asks State to Step In

Apr 26, 2022 -

Pete's Pot Flop

Feb 13, 2020 - More »

more from the author

-

A Brief History of Dildos

- Apr 11, 2024

-

Eclipse!

- Mar 28, 2024

-

The Little Drone that Could

- Mar 14, 2024

- More »

Latest in Field Notes

Readers also liked…

-

Trouble on the Line: The Reality Part 2

- Nov 3, 2022