Conflicting Reports

People seem to think violence is on the rise in Humboldt, but is it?

By Thadeus Greenson [email protected] @ThadeusGreenson[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Shortly after Sandra Lingle moved to Eureka from San Diego 32 years ago, something made an impression. "I saw somebody walking their dog at 11 o'clock at night — a woman — and I was thrilled," she recalled last week. To Lingle, the sight reinforced that she'd moved to a safe place, a community where she could walk down the block at night without looking over her shoulder.

Over the ensuing decades, Lingle walked all over Eureka from her little home tucked off H Street, paying little heed to the time of day or night. That's changed in recent months. "I think it's just too crazy," she said. "I don't go out late, or at like 5 a.m., like I used to. I think crime has really gotten bad. It's increasing."

It's a claim you hear everywhere — at barbershops, coffee houses and huddled around water coolers — and one you see splashed across social media outlets: Humboldt County, and Eureka especially, is growing more violent, more crime ridden. It seems to be reinforced with every headline: a priest brutally killed in Eureka; a man stabbed to death in Trinidad; three people violently slain in Arcata last year.

But criminologists and data tell us crime is on the decline across the nation and the state. In fact, stats from the California Department of Justice indicate that in 2012 — the last year for which statistics are available — Humboldt County recorded the fewest number of reported violent crimes in more than a decade. So, what can we make of these statistics that so clearly fly in the face of what many on the North Coast are feeling? Is there a disconnect between perception and reality? If so, how do we feel safe again?

California's violent crime rate hit a 45-year low in 2011, the result of a couple of decades of steady decline since 1992, when the state peaked out at 11.2 reported violent crimes per 1,000 residents. Despite a slight uptick in 2012, the state violent crime rate remained at a near-historic low, with just 4.22 reported violent crimes for every 1,000 residents, just a skosh above the national rate of 3.87.

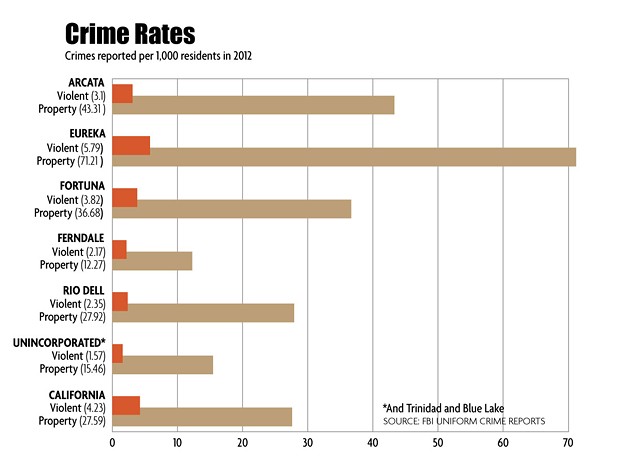

According to the California Department of Justice, Humboldt County's violent crime rate came in at 2.89 per 1,000 residents, far below the state and even national averages. For the most part, cities around the county enjoyed similarly low numbers in 2012 — 3.82 in Fortuna, 2.17 in Ferndale, 2.35 in Rio Dell, 3.1 in Arcata. Overall, in 2012, Humboldt County seemed a fairly safe place for people to live, according to the data.

There is, however, a notable exception. Eureka, the county seat and Humboldt's social and economic epicenter, far outpaced the national and state averages, recording 5.79 reported violent crimes per 1,000 residents. That's a violent crime rate that outpaces cities like Long Beach, Fresno and Los Angeles, according to the FBI, but one that pales in comparison to the state's worst, Oakland and Stockton, which recorded 19.93 and 15.48 violent crimes per 1,000 residents, respectively.

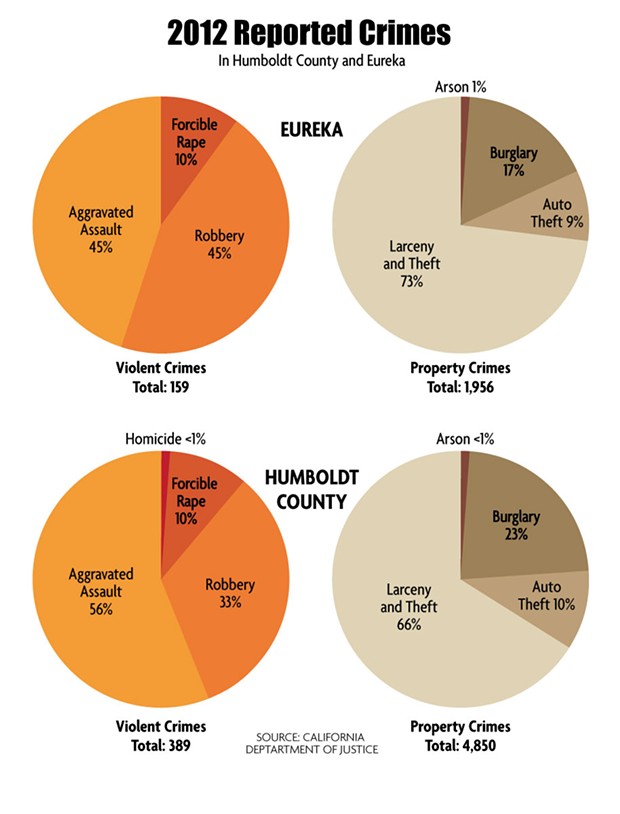

But violent crime — homicides, rapes, robberies and assaults — is only one component to community safety, and the statistics clearly show that while you may be comparatively safe in Humboldt County, your car stereo is not.

In 2012, the state recorded a reported property crime rate of 27.59 per 1,000 residents, a more than 7.5 percent increase from 2011. If Humboldt County's rate was comparatively high, coming in at 35.97, Eureka's were astronomical at 71.21, according to figures from the FBI.

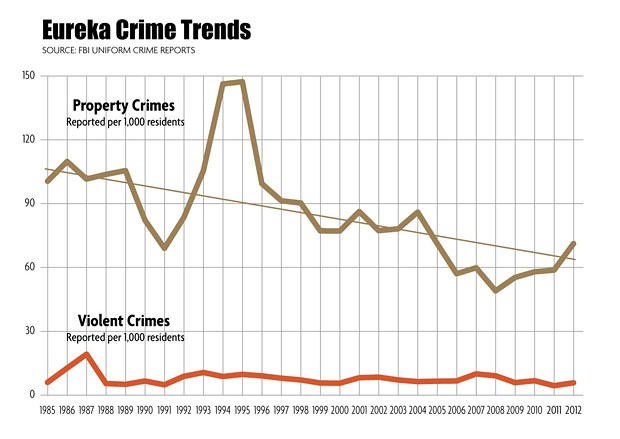

But Eureka's property crime numbers have always been staggeringly high, and the rate of 71.21 recorded in 2012 was less than half that recorded in 1994. From 1985 through 1995, Eureka's property crime rate topped 100 eight times, according to the FBI data, which also indicates the city's property crime rates were at a historic six-year low until ticking up 17.5 percent from 2011 to 2012.

Similarly, Eureka's violent crime rates have seen a modest and gradual — if somewhat inconsistent — downward trend since a record high of 19.23 in 1987. Since then, the city has seen five-year averages of 6.17, 9.23, 7.02, 7.33 and 6.39 over the last 25 years. So, yes, Eureka's violent crime rate is alarmingly high for a city its size, but it has been for a long, long time.

If you talk to sociologists and criminologists, many will tell you that gauging the safety of a community purely by crime data is a fool's errand. First and foremost, it's important to note that the largest databases on California Crime — the FBI's Uniform Crime Reports and the California Department of Justice — only include crimes that were reported to the police.

Gary Sokolow, a criminologist who teaches at College of the Redwoods' Police Academy, said studies indicate that only about half of all crimes committed wind up being reported to authorities. "Due to victims' apathy, shame, fear, etc., for every 1,000 actual crimes anywhere, only about 500 get reported," Sokolow said. "Right away, 50 percent of crime comes off the charts."

Then, others point out, there's the fact that the two databases rely on law enforcement agencies to self-report their data, which is problematic on a number of levels. First of all, Eureka Police Chief Andrew Mills points out, there can be huge discrepancies between how agencies report. For example, a small agency that has a volunteer compiling and reporting its data might not report as comprehensively as a larger agency with a full records division.

In some cases, sinister motives can also sway statistics. For example, a police department under pressure to get a handle on crime might underreport, classifying rapes as assaults, robberies as thefts and violent assaults as disorderly conduct calls. The phenomenon was famously summed up as "juking the stats" by Roland Pryzbylewski, a character on HBO's crime drama "The Wire." "Making robberies into larcenies. Making rapes disappear. You juke the stats, and majors become colonels," he said. Statistics can also get juked in the other direction by agencies pushing for larger budgets to tackle crime problems. Sokolow pointed to the infamous quotas enacted by the New York Police Department in an effort to show the public it was cracking down on crime.

"Statistics can lie and be manipulated," Sokolow said. "It's like the accountant who is asked, 'How much is two plus two' and answers, 'How much do you want it to be?' (Crime statistics) are kind of a mixed bag. The best I can tell you is it's just a very rough indicator."

Even in situations without nefarious intentions and where reporting is uniform and spot on, crime data doesn't travel in real time. Consequently, we're talking about crime problems today while looking at statistics from more than a year ago. This is especially problematic at this particular moment in time, when California prison realignment is a new reality. While studies by Stanford University and the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice have found there to be no evidence that realignment has caused a spike in violent crime, there's no data we can turn to on a local level. Instead, we're left to anecdotal evidence (law enforcement officials say there's been a spike in property crime since realignment but violent crime has remained fairly steady).

Meredith Williams, an assistant professor of sociology at Humboldt State University, also cautions that crime data can, in essence, become a self-fulfilling prophecy. Sometimes, data will indicate that a certain city or neighborhood has a high crime rate, which will cause police to focus extra attention there to address the problem, resulting in more arrests and more crime reports, which will drive the crime rate up even further.

On the national level, Williams said the Bureau of Justice Statistics' Crime Victimization Survey may be the best gauge of crime rates. For the survey, the bureau collects data from a sample of about 90,000 households, questioning all residents over the age of 12 about the frequency, characterization and consequences of crime in the United States. The bureau uses the survey results to measure the amount of crime that goes unreported in the country, as well as to correlate victimization rates with demographic information. Generally, the survey estimates higher crime rates than law enforcement agencies report. In 2012, the bureau estimated that 22.6 people per 1,000 U.S. residents fell victim to violent crime. The problem with the survey, however, is it doesn't reach enough households to come up with regional data, so it's of little use in estimating crime rates in Humboldt County.

So, with all these flaws, does crime data even help inform the discussion? Is it worth paying attention to? Humboldt County District Attorney Paul Gallegos thinks so.

"It has to be," he says. "It's the only way we have to measure."

If one is willing to accept the flaws and use crime data as the starting point for a discussion about local public safety, two questions immediately come to the forefront: What is going on in Eureka? And, why is my car stereo less safe in Humboldt County than in other parts of the state?

There's a number of websites out there that rate the quality of life in various cities. Eureka never seems to score well when it comes to safety. The website neighborhoodscout.com, for instance, claims Eureka is safer than only 2 percent of United States cities. To make this claim, the site simply adds violent and property crime together and figures out how many crimes are committed per 1,000 residents.

Speaking from Eureka Police headquarters, Mills said he's aware of Eureka's low rankings on these sites, but said he doesn't see the city as some lawless wasteland. Mills also doesn't believe there's been the huge spike in violent crime that's being talked about around town. But he gets why people are frustrated. "I think people are generally just tired of crime, and I understand it," he said. "It's not something we can just excuse and shy away from. We have some crime problems. I don't know how else to put it."

Back from one of her walks through town, speaking in her home off H Street, Lingle said she sees a clear culprit in Eureka. "It's the meth that's doing it," she said. "All the screaming and yelling, it's just making people crazy." Many in town also point to meth as the primary factor causing crime, but Mills sees the answer to Eureka's high crime rates as being a lot more nuanced and a lot more complicated.

Mills said it's important to recognize that while Eureka's population sits around 28,000 — and its per-capita crime statistics are calculated accordingly — the city has a daytime population that's probably closer to 60,000. Humboldt County Sheriff Mike Downey agreed, saying Eureka's per-capita numbers are skewed. "You have to remember Eureka is the heartbeat of Humboldt County," he said. "All of the county services come out of Eureka. People come here to trade, to buy, to sell — everything happens in Eureka."

While he believes the per-capita numbers can be deceiving, Mills said he thinks crime data is a very important tool, but one that only tells part of the story. Mills said he likes to "drill down on the data," peeling back the layers by looking at specific cases and by using the data to map crime intensity in specific neighborhoods. When Mills spoke to the Journal, he said he'd just finished paging through last quarter's crime reports.

"It was astounding how many of those (crime victims) were people engaging in risky behaviors," he said. "When you look at it overall, many of Eureka's violent crimes involve people who engage in those types of behaviors. In other words, if you sell dope, you have to understand your chances of having a home invasion robbery go up. If you pick up a prostitute, not only do your risks of venereal disease go up, but your risk of becoming a robbery victim goes up as well."

But that's clearly only part of the problem, Mills said, noting that 45 percent of Eureka's violent crimes in 2012 were aggravated assaults, many of which he said were situations where an argument turned violent. "We seem to have a lot of people who don't have the capacity to deal with interpersonal conflict, for whatever reason," he said. Mills, a relative newcomer to Humboldt, having taken over EPD just a couple of months ago, said he's also struck by an "underground, outlaw" culture in Humboldt that he thinks may contribute to Eureka's crime problems.

When it comes to property crime, local law enforcement officials pointed to a host of contributing factors. "The research would suggest that with drug addiction comes property crime," Mills said. "We certainly have plenty of addiction here."

Downey pointed to the economy. "Especially with the crimes of convenience, I think we're looking at a population that's depressed economically," he said, adding that the depressed economy also leaves cash-strapped local governments with fewer officers on the streets. "I think there's a correlation between the two."

Williams, the assistant sociology professor at HSU, moved to Arcata about six months ago from Vancouver, Wash. She was a bit shocked when her landlord showed her the security system he'd installed in her rental.

"I kind of started from this place of fear," Williams said. "Even as someone who studies crime and knows how overinflated public fears can be, I still haven't figured out how safe this area is yet." Williams said she sees conflicting information on the ground in Humboldt. First, there are the numbers, which seem to indicate there's a problem here. But Williams doesn't necessarily see crime rates and data as the best gauges for a community's safety.

"Areas that have high levels of collective efficacy seem to have lower crime rates and greater feeling of public safety," Williams said. "Here, you still have that. You still have neighbors looking out for one another and talking to each other. So, generally, I'd say [Humboldt] is doing really well."

But if Humboldt still has that neighborhood unity Williams referred to, and there doesn't seem to a large spike in local violent crime rates, then why don't people feel safer? "It's hugely a matter of perception," says Sokolow down at CR. "The media drives this furiously... And, one big case can really distort people's view of public safety. One horrific case can really put people on edge."

The county has certainly had a string of shockingly violent, high-profile crimes in the last couple years. In late 2012, police believe a Hoopa woman was tortured to death in her home by a man who then drove to Eureka and intentionally ran down three women runners. In May, two young people where shot and killed at a home in Arcata. In September, a man was shot and killed with a crossbow out on the Samoa Peninsula. Two months later, a man was stabbed to death in downtown Arcata. Then there was the slaying of a beloved local priest, Eric Freed, on New Year's Day in Eureka. These cases have drawn loads of local — and sometimes national — media attention, with some regularly reappearing in headlines with coverage of court hearings.

It seems clear that these crimes, and coverage of them, do feed public perception, though it's unclear whether they simply serve to reinforce a view that's already there or actually change peoples' opinions. Many — including Lingle — point to Freed's slaying as evidence that violent crime is on the rise locally.

But it's not just the media, Gallegos said, that shapes the public's perceptions of safety, it's politicians running for office, local police agencies lobbying for funding and local officials opining about state policies, like realignment. "I think we all have to take some responsibility for that as community leaders," Gallegos said, adding that people all too often use fear as a tool to get votes, lobby for or against a specific policy or to bring funds to their agencies.

But, this is also a larger societal issue, according to Williams, who says she feels that nationally there's a disconnect between people's perceptions of community safety and reality. "We feel we need to be afraid, but we don't," she said. "We're fortunate to be living at a time when crime rates are really low." Still, people feel unsettled, she said, pointing to media in the digital age as a huge reason. "If you consume any media at all, we're constantly being fed this stream of mass killings, school shootings and violent crimes," she said. "It happens, and it becomes so pervasive — cameras are there instantly and you're seeing people crying, big graphics and gory images. It's just so intense. It's relentless and we're surrounded by it."

There may be other factors locally too. "When people look at their environment and see disorder, that causes fear," Mills said. More closed businesses, dilapidated buildings, trash in the streets, homeless people and transients milling about and drug addicts roaming downtown can all impact a person's feeling of safety. "That can make things feel worse than they are," Mills said.

When talking about how to feel and become safer as a community — regardless of whether crime is spiking or holding steady — there are no easy answers, no one-size-fits-all approach, Gallegos said.

For one thing, Humboldt's safety problems extend well beyond crime. According to a report from the county Department of Health and Human Services, local deaths due to unintentional injuries, alcohol and drug overdoses, car accidents and suicide all far outpace state averages. But even if we look solely at crime, most agree more police on the streets and larger jails by themselves won't solve the problem.

Law enforcement officials say some extra caution and awareness — basics like not leaving homes and cars unlocked, avoiding risky behavior and taking valuables off your car seat — would go a long way toward lowering crime rates simply by taking away low-hanging fruit. From there, the answers grow more complex.

Gallegos said he thinks investing in and reforming the education system has to be part of the conversation. The district attorney said studies have shown very strong correlations between a lack of education and criminality — so strong, in fact, that he says Texas has begun planning the construction of new prisons based on high school graduation rates.

No only does dropping out of school leave a person with fewer professional prospects, Gallegos said school is also where most people learn effective interpersonal communication, life skills and "ways to express anger and frustration without violence." Finding ways to keep kids in school, Gallegos said, will result in a safer county.

Some officials also point to better systems to treat and care for drug addiction and mental illness as key components to making Humboldt County a safer place. Other people say more neighborhood watch groups are in order. While she agrees with all those endeavors, Lingle also sees a simpler approach.

"I think more people getting out and walking would help a lot — that's what we used to do in the '50s," she said. "Because I walk, I see a lot of things. It's not just because I'm a nosy old lady. Just getting more people out and about — riding their bikes, walking and skateboarding — if we could get more of that, I think the whole town would be safer because most people who are up to no good don't want you to see what they're doing."

To stress her point, Lingle pointed to the Hikshari' Trail that runs along Eureka's waterfront. Go down there on a weekday, when few people are out walking and running, and Lingle says you'll see all kinds of unsavory activity, from drug deals to fights. But, return on a weekend when the trail is bustling with recreation, Lingle said, and those unseemly elements are nowhere to be found.

To hear Lingle tell it, a more active community would also result in a more connected community, as neighbors would run into each other on the streets, share stories and talk about problems in the area. If folks don't feel safe doing it, Lingle said, they should start by taking after-dinner walks with small groups of neighbors or in twos and threes. "I think that would help a lot," she said.

If you believe Williams' theory that community togetherness is the best gauge of community safety, then Lingle's idea seems to have some merit. If nothing else, it might make people feel safer. And, ultimately, Williams believes perception might be just as important as reality.

"Maybe that's what matters more than the actual crime rate," she said. "Do you feel safe walking to the corner market? In the end, that matters more than whatever the FBI says the crime rate is in your neighborhood."

For a national take on the issue, check out this infographic from the Christian Science Monitor comparing crime rates to perceptions of community safety in various cities throughout the United States.

Speaking of...

Comments (7)

Showing 1-7 of 7

more from the author

-

Seeking Salvation

'Living in amends,' a candidate for resentencing hopes for another chance

- Apr 18, 2024

-

UPDATE: Artillery Shell Deemed Safe in Ferndale

- Apr 12, 2024

-

Turning the Titanic

Cal Poly Humboldt recognized for leadership in addressing global plastics crisis

- Apr 11, 2024

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023