Carving Space

For the first time in decades, an Asian-American themed art show hits Eureka

By Ken Weiderman, Heidi Walters, Jennifer Fumiko Cahill [email protected] @jfumikocahill and Thadeus Greenson [email protected] @ThadeusGreenson[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Robert Sataua's black-rimmed glasses reflect the evening light that streams into his Arcata Bottoms home. A shock of dark hair stands up straight on his head. Neatly trimmed whiskers line his chin. He's in the thick of organizing the show Hungry Ghosts, which opens this weekend at the Ink People's Brenda Tuxford gallery for Eureka's Arts Alive!. It is the first Eureka exhibition in two decades to gather Asian-American artists into one venue, and Sataua is excited. Defined more along geographical lines than cultural or ethnic boundaries, the show features artists who identify as Asian or Pacific Islander.

Sataua's excitement goes beyond the realm of visual arts. For him, this is a community-building opportunity. We may live in a culture that claims to be inclusive of every ethnic group, but the reality is that even on the North Coast Asian communities have not had it easy. In 1885, Eureka's entire Chinese population was loaded onto boats and shipped to San Francisco. During World War II, Japanese-Americans were interned at Fort Humboldt against their will. Rebuilding a cohesive community hasn't been easy, and the effects of these injustices linger to this day.

Communities are alive, though. They grow and change, and flourishing requires patient, dedicated work. Relating to the struggle that many Asian cultures have faced in California, Sataua sees this show as an opportunity to build a safe space for people to express themselves. "If you don't carve out that space," he says, "then it's not there for you." While it's been difficult to reach out to all of the diverse Asian-American communities in Humboldt County, this show is really about opening up to a larger circle of Asian-American artists. In that way, it has already succeeded. "There's a certain amount of pride to identifying as a member of this community," says Sataua, "possibly because there's not a venue for that expression."

The Ink People have a long history of working with traditional and folk arts, but Sataua has opened this show to all forms of visual art. While some of the artists draw from the conventions of their respective cultural heritages, many break from the predictability of tradition to forge their own artistic styles.

Indeed, those expecting a certain aesthetic might be in for a surprise. Some viewers may have preconceived and limiting notions of Asian-American art. And the very act of defining a show based upon a particular ethnic group can stifle both artists and viewers alike. To counter this, Sataua specifically sought artists who find contemporary interpretations of traditional art forms along with those who work more conventionally. The result is a show that freely allows people to express themselves and define who they are. "If you have roots from Asia, what's not Asian about your artwork?" Sataua asks.

Hungry Ghosts also has a personal connection. Although Sataua doesn't immediately identify as an artist, he feels that living his life in a creative way helps him maintain a connection to the traditional arts of his heritage. Whether it's crafting hip-hop beats or designing elaborate silk-screened patterns, he readily embraces the opportunity to create works that define and speak to his Samoan lineage. "I'm trying to hold onto my roots," he says. "The importance of the art isn't so much its aesthetic sense, it's what it represents as a documentation of culture and heritage."

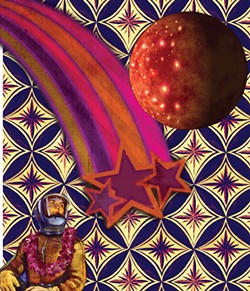

Siapo, a thousand-year-old art form incorporating dramatic, repeating patterns, is a major influence. Using an iPad to photograph original drawings, Sataua reinterprets siapo prints based upon the natural world and incorporates them into contemporary images. For this show, he has created a series of pieces that comment on Samoan culture in the 21st century. Couched in a "Samoan Space Odyssey" theme, his whimsical compositions allude to Internet memes, Dadaist frivolity and "low-art" aesthetics. Distinct island color palates and traditional patterns mash up against space suits, shooting stars and planets.

Much like Sataua's Samoan space images, the artists represented in Hungry Ghosts have threads of Asian ancestry that stretch both to the past and future. Utilizing traditional forms and folk sensibilities, their art defines who they are in today's world. Beyond widening the circle of the Asian-American art community, the show itself gives viewers the opportunity to witness the diverse range of artistic talent and aesthetic variety within this group.

Sataua turns up the corners of his mouth in a smile as he talks about the incredible support from Ink People to make this show happen. Although there's still a lot of work to do, he's looking forward to the Arts Alive! opening. If you'd like to go, take the elevator to the third floor of the Healy Building in Old Town and enjoy the beautiful space that is the Brenda Tuxford Gallery. Who knows? It might be two decades before another show like this happens. Let's hope not.

Read on for profiles of four other artists in the show.

— Ken Weiderman

The Sisters Be

The first time Cate Be laid her hands on clay and began shaping it, she got excited. It was like being a kid again — and, better yet, it took the former performance musician turned scientist back to her artistic side.

"I loved going to the store with clay in my hair and on my shirt," she says, laughing. "I wanted people to know I was working with it."

We're sitting on a sunny bench outside the Fire Arts Center in Arcata. Shelves on either side of us are heavy with student ceramic works. Inside, more shelves hold works still arranged for a recent student art show. Be's are there, along with works by her sister, Jennifer Be, who soon joins us.

The sisters' styles differ, but both are nature-inspired. Cate's work includes wheel-spun mugs textured with fern and redwood leaf imprints — one has a sculpted fish tail for a handle — and a planter shaped like a pair of sturdy feet. Jennifer's includes a pair of small, curvy vessels shaped with thin clay slabs, one a planter/pond combo, the other just a pond. For the student show she put tiny fish in the ponds, but they kept jumping out.

The Bes started slinging clay last summer, when Cate's partner's mother gave her an early graduation gift of lessons at Fire Arts. Cate, 31, was finishing her ecological restoration degree at Humboldt State University. Jennifer, 26, who is a senior clerk and deli chef at the Arcata Co-op, took the class with her.

Both sisters have long had artistic leanings. Cate grew up thinking she'd be a professional musician and performed in her youth on trumpet, piano, flute or "whatever instrument was needed." Now she's learning mandolin. She sketches, paints and knits.

Jennifer was more outdoorsy and into sports as a kid, but she also learned carpentry and took art classes. She got excited about ceramics after housesitting for a couple who had made their own dishes.

"Everything I was eating on they'd made," Jennifer says. "I'm inspired by necessity, because I make what I need."

The sisters grew up in Southern California. At 19, Cate moved to Houston. Jennifer, at 17, joined her; eventually they moved back to Riverside. Cate had a phlebotomy license and was studying to be a pharmacist. But backpacking trips in Texas inspired her to change course. In 2010, Cate enrolled at Humboldt State University. Now she runs her own native gardening and landscape business and dreams of joining the Peace Corps and living in Cambodia and El Salvador — where the sisters' father and mother, respectively, are from.

Jennifer got into Le Cordon Bleu College of Culinary Arts in San Francisco, but her student aid fell through. She moved to Humboldt over a year ago and plans to study social work and "maybe do something that ties into nature and therapy; maybe open up a camp for youth ... maybe move to Central America or maybe open a little café with my sister."

"I'm fighting a lot of interests," Jennifer says.

She was excited to be included in Hungry Ghosts. Cate was perplexed.

"I didn't see that I make things with an 'Asian' eye," Cate says. "But the person who invited me said, 'We are challenging the idea of what an Asian artist puts out.'"

The idea of ethnicity gets confusing, says Cate. She looks more like their dad, so people call her Asian. Jennifer looks more like their mom and gets called Hispanic.

Cate's dad, though reticent about his past, taught her to say "I want to eat rice" and "I love you" in Khmer. Jennifer recalls a seven-day ceremony for a departed great uncle. Monks flew in from Cambodia, and she got to eat ant larvae that tasted like the lemon tree the ant nest had been in.

"I see this show as a way to honor that part of my heritage," says Jennifer.

— Heidi Walters

Yoshi Makino

Cultures on every continent build with mud. The earth plasters used on houses all over the world have what Yoshi Makino calls a presence — organic, imperfect surfaces and a history going back thousands of years. "Particularly earth plaster has a real presence," she says. "I'm trying to harness that and make it aesthetically interesting."

Her piece "Offerings to the Hungry Ghosts," is a triptych of framed earth and lime plaster panels. In the center panel she's blown a mixture of soot, green tea, ash and cinnabar over hands, leaving ghosted silhouettes like the earliest cave painters did. On the left panel, there is a thick spiral of green tea leaves against white background, and on the right one a soot-blackened plaster is embedded with scattered grains of white rice.

Over the phone from her home in Ukiah, Makino says, "I've been kind of interested in minimal images, geometric shapes and forms in nature." It was a challenge to keep the tea from oxidizing and losing its color when mixed with the alkaline lime mixture, and Makino took time tinkering with plaster recipes until she was satisfied. "Lots of small samples," she says, sighing into the receiver. Typically it's finalizing the idea for a piece that takes longest, but she was inspired by the title of the show.

Buddhist and Asian traditions of honoring ancestors and making offerings to "unfulfilled ghosts," those who didn't have a good burial, speak to Makino. "I think it's very important to have a connection to your ancestors," she says. "It doesn't have to be a thing where you necessarily knew them or got along with them, but having a connection can be empowering ... to know where you came from and to help you keep going."

Makino, whose sister Annette Makino is also in the show, originally began her art career with photography before growing frustrated with working in two dimensions. At the California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland, she started incorporating three-dimensional elements and, by the time she finished her MFA in studio art at Irvine, she was doing a good deal of installation work. After a few years in Arcata designing jewelry at Holly Yashi, Makino decamped for warmer weather.

In a way, Makino is still exploring spaces with her day job building straw-bale houses, made by covering stacked hay with a muddy natural plaster that breathes and keep the straw from rotting. When tinted with other natural ingredients, the earth or lime mixtures are also decorative. Makino first learned the skill from a friend who worked with Native American adobe. Makino then sought out a master of Japanese earth plaster to learn to use tools and methods for building traditional houses that still stand in parts of Japan, where she lived for half a year as a small child.

Those skills have fed her artwork, too. "It's one of those things where before you can break the rules, you have to know the rules." On her website are images of the mounted earth plaster discs she makes, purposely cracked like a desert floor — exactly the effect she avoids when working on houses. She muses that her freedom to rebel comes from her Japanese-born mother, while her exactitude is from her Swiss father.

In addition to showing with her sister, Makino is excited about the prospect of joining other Asian-American and Pacific Islander artists, "especially here in Humboldt and Mendocino, where there aren't as many." She notes that a similar group show in the Bay Area wouldn't be such a big deal. "It's also interesting for me to see my work in this context," she says. Asked if she has any hungry ghosts in her life, she laughs. "Sure, but I'm giving them offerings so I think they'll be sated!"

— Jennifer Fumiko Cahill

Brian Kaneko

In a modern world of convenience and instant gratification, Brian Kaneko's art depends on patience and pain. Literally.

"There's nothing fast and nothing painless about it," Kaneko says as he slowly works his tattoo needle, filling in a skull on the back of a young man from Chico who Kaneko estimates will spend as many as 50 hours feeling the steady sting. "I think it's a very real experience. You really have to earn it."

Kaneko saw his first tattoo as a 15-year-old half-Japanese kid growing up in the Bay Area suburb of Walnut Creek. It was a work of art on the skin of his mother's then-boyfriend, Kaneko recalls, inked by the legendary Ed Hardy, who Kaneko dubs the "most important American to the melding of fine art and tattooing." Kaneko was hooked.

"I just didn't even know something like that was possible," he says. "From that moment on, I always knew I would get a tattoo." As soon as he turned 18, he did just that.

With a passion for comic books and parents who were both interested in art — especially lithographs and etchings — Kaneko, in retrospect, sees tattooing as a natural fit. After all, in its artistic essence, tattooing is taking deep, black lines and filling them in with color. By the time he showed up at Humboldt State University in the fall of 1995 looking to find someplace that was "the opposite of suburbs," he was obsessed with tattooing.

He says he was a lackluster art student — disinterested and unmotivated — who spent all his time either getting tattoos or reading about them. Then he had "one of those light bulb moments," as he puts it. Within months, he'd quit school and started tattooing full time. "My parents were not pleased," he says. "It wasn't just a casual thing to say, 'I'm going to drop out of school and start tattooing.' They weren't that into it."

But, some eight years later, Kaneko is nothing if not a local success story. He's run his own local shop — Arcata's True Nature Tattoo — for seven years, and regularly travels to New York, San Francisco and elsewhere to do guest appearances in other people's shops. He has a following of folks who seek him out for his trademark, traditional Japanese-style work.

Kaneko says he loves the partnership tattooing forms between artist and canvas. First, there's the collaboration as he and a customer consult over several meetings to come up with a vision. Then, he sketches out the tattoo. Finally, it's time to spend hours needling it into the client's skin. "When you are drawing a tattoo, you are an artist but, when you're applying it, you're much more of a craftsman," he explains. When he's finished, his work gets up and walks out of his studio as a part of the person who commissioned it. "It's an interesting bond," Kaneko says musingly, still working his needle into the guy from Chico.

Asked about the upcoming Ink People show, Kaneko says he's excited to be a part of it, but concedes he only agreed to join in because the curator, Robert Sataua, was so persistent. Kaneko says he's planning on showing a couple of his paintings. Maybe, he says, he'll bring a few photos of his tattoo work. But, he explains, the acceptance of tattooing as art is still very much a work in progress. While it's his Japanese heritage that inspires his style, Kaneko notes that the art form remains very taboo in Japan. It's much more accepted in the United States but doesn't exactly transfer to a gallery setting.

"Where does tattooing fall in the world of fine art?" he asks. "It's still a debate that doesn't really have an answer." But Kaneko has patience. And he can take a little pain.

— Thadeus Greenson

Speaking of...

-

Disaster Response, Crowley, Art in Piles and Salsas

Sep 7, 2023 -

Remains Recovered from Trinity River in Hoopa

Jul 5, 2023 -

NCJ Preview: Abalone, KHSU and Help in the Storms

Jan 15, 2023 - More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023