[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

The future isn't what it used to be. (Yogi Berra, maybe)

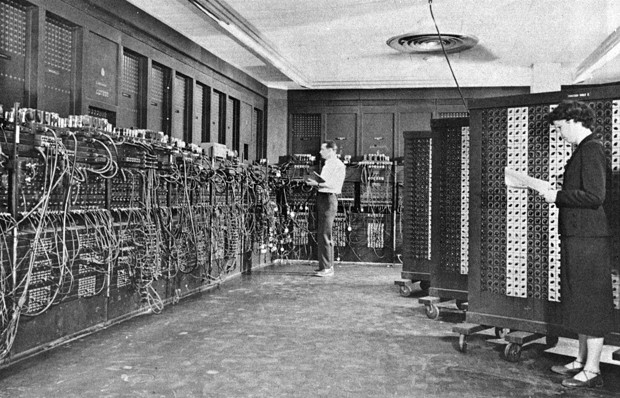

I'm about three years older than ENIAC, the first general-purpose electronic computer. ENIAC, which stands for Electronic Numerical Integrator And Computer, was a "Turing-complete" digital computer, that is, capable of being reprogrammed to solve virtually any numerical problem. ENIAC, which weighed nearly 30 tons and took up the space of a house, needed 150 kilowatts of electricity to run, and contained 17,468 vacuum tubes, 7,200 crystal diodes, 1,500 relays, 70,000 resistors, 10,000 capacitors and millions of hand-soldered joints. Built in 1945, it performed at a speed of 18 calculations per second and cost about $6 million in today's dollars.

I'm writing this column at Old Town Coffee & Chocolates on my iPad2, cost today: $399. Weighs 36 ounces, with Bluetooth keyboard and cover; smaller than a magazine; battery lasts forever, to a first degree of approximation. Speed: 1.7 billion calculations per second.

I suppose every age looks back at a previous one and remarks on how far it's come. Phoenician scribes probably scoffed at old-fashioned cuneiform writing. The architects of the first Gothic cathedral might have scorned the builders of those squat Norman piles of stone. I bet John Dunlop, bouncing along Belfast's cobbled streets on the new pneumatic tires he'd just invented, pitied bicycle riders of his dad's generation. But I do believe that the shift in my own lifetime from ENIAC to iPad, from analog to digital, from two-week international aerograms to IM, represents more than a gradual, routine evolution of technology from one generation to the next. Hackneyed as it is, the phrase "quantum leap" really means something today. Change, for better or worse, is spiraling way beyond my ken.

Take knowledge in broad, raw terms. Used to be, one person could be the repository of a fair summary of the world's knowledge. Leonardo da Vinci was the original "Renaissance man," although the same polymath sentiment might be applied to Aristotle, Francis Bacon, Thomas Jefferson, Johann von Goethe, "our" Alexander von Humboldt and H.G. Wells. No longer: too much knowledge, too many areas of speciality, too small brains. (Google processes 10 times the 2.5 petabyte -- that's 2.5 times 10 to the 15th power -- memory capacity of the human brain every day!)

What's a sane reaction? Shock and awe? Humility? Fear? Another glass of Great White microbrew? My own response to the threat of data overload -- coupled with exponentially increasing processing power -- is to surrender some of my need to know. Instead, I find myself simply enjoying the questions, of which there are plenty. According to the late "grand old man" of American physics, Princeton professor John Archibald Wheeler, just three problems will keep us happily occupied for the next 500 years: the universe, consciousness and quantum theory. I'd settle for simply (!) posing the right question on just one of these.

Barry Evans ([email protected]) doesn't even know if he's passing through time or if time is passing him by.

more from the author

-

A Brief History of Dildos

- Apr 11, 2024

-

Eclipse!

- Mar 28, 2024

-

The Little Drone that Could

- Mar 14, 2024

- More »

Latest in Field Notes

Readers also liked…

-

Trouble on the Line: The Reality Part 2

- Nov 3, 2022