[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

This solstice, 24 Eureka photographers came together to document the day's passage for 24 Hours, 24 Photographers. Humboldt State University photojournalism professor (and freelance photographer for the Journal) Mark Larson, who organized the project, invited each photographer to shoot during a prearranged hour-long time slot. Any type of film, digital camera, and/or lighting was permissible but all pictures had to be shot within Eureka city limits.

To find participants, Larson drew on his extensive network of contacts in the community. He assembled a diverse group of shutterbugs ranging from students to photojournalists to commercial specialists and fine arts professionals. He took a hands-off approach for the most part, occasionally aiding the process by offering gnomic words of encouragement. "'Let the photograph come to you,' that was always Mark's advice," Brandi Easter affirmed.

"As photojournalists, we're trained to overcome our natural shyness and approach strangers," Larson noted. "But not everyone in this exhibition is a photojournalist. Some were shy about going up to strangers; others found themselves intrigued by the experience." Some exhibitors produced works of classic street photography; others interpreted Larson's brief in a more expansive way, making still lives, landscapes and portraits that sought to summarize the Eurekan zeitgeist.

Larson photographed between 6 and 7 a.m. He asked himself: What events would be going on in the city at that hour? "My original plan was to show up at the Eureka Rescue Mission at 6 a.m., when the homeless people get booted out onto the streets. But I censored myself from taking the pictures that I planned. This was in part because I was dealing with my own internal shyness. And in part it was because once I got there, I didn't feel like I wanted to intrude onto some unfortunate person's life at that particular moment. But then I looked across Halvorsen Park and the photo found me — it was the camp of a sleeping homeless person with the Carson Mansion visible in the background."

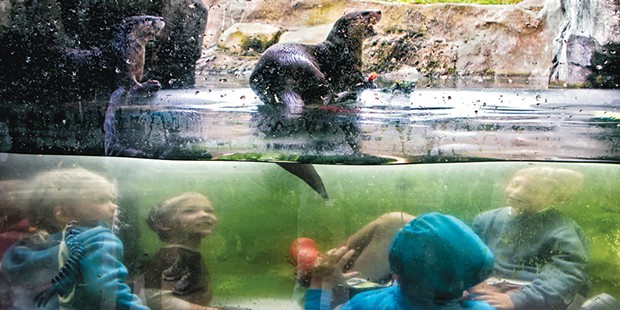

Later that morning, Dana Utman adopted a more directed approach. He brought his camera to the Sequoia Park Zoo between 10 and 11 a.m. with a goal in mind: "I wanted to see if I could capture animals and children together." He chose an hour when he knew that the animals would be astir. Zoo staff helped out by feeding the otters, drawing both people and animals to the place he wanted to photograph.

Zoo photos make many of us reflexively hearken back to The Animals, Garry Winogrand's 1969 zoo collection described by photo historian John Szarkowski as, "even if true ... a grotesquery." While that photographer's viewfinder often seemed to scorch what it framed, Utman's image is serene. The picture plane is split by the air-water divide. Above and below the water line, a triangulating child-otter-child composition generates gravitas. An otter rears up at the triangle's apex, its teeth shining in the sun. Down below, little kids viewed through curving plexiglass laugh in what appears to be a pellucid, moss-green, underwater world.

For Utman, the shoot went according to plan. But for other photographers, the hour turned into an exercise in crisis management. "What I thought I was going to shoot didn't work out at all," Monica Topping remarked. She had chosen her 6 p.m. time slot with twilight effects in mind but failed to reckon with light conditions on the longest day of the year at 40.8021 degrees north latitude. "It was like midday light. I had wanted to shoot from the roof of the Eureka Theater, but then I realized that up there I was eye level with every single power line in the city." Undaunted, Topping at first tried "getting creative with some pigeons up inside of rusty I-beams," but ended up dashing across the city on a whim instead. She found herself in the leafy confines of Sequoia Park with fewer than 20 minutes to spare, in search of an antidote to urban grit. The clock was ticking but Topping spied "one single bright red ripe thimbleberry" overhead. Taking the right picture turned out easy in the end.

Larson cited as inspiration the popular "Day in the Life" photography series, as well as the "Project 24" photo shoot staged more recently in San Francisco. Going back farther, the work of midcentury street photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson has been important to him. So has Cartier-Bresson's influential notion of the "decisive moment" in photography. As the French photojournalist explained to an interviewer in 1957: "There is a creative fraction of a second when you are taking a picture. Your eye must see a composition or an expression that life itself offers you, and you must know with intuition when to click the camera. That is the moment when the photographer is creative. ... The moment! Once you miss it, it is gone forever."

While many of these photographs testify to the enduring influence of Cartier-Bresson's ideal, the stories behind them — made legible with extended captions — clarify just how much the definition of "decisive moment" has been changed by digital technology. Contemporary photographers have a different relationship to plurality and perhaps to time itself.

When Easter shot a moody nocturne sequence of green streetlights at the intersection of Fourth and I streets between 3 and 4 a.m., she "was surprised by the way that the appearance of the streetlights changed when I closed the F-stop. As the aperture got smaller, the streetlights started to elongate and look like stars. People who saw the photographs asked me if I had added some kind of star effect (in post-production). I have no idea how it works out in terms of the physics or the optics. But the star effect was interesting and real. It ended up adding to the sense of mystery and quiet that the street possessed at that hour."

"I got to use my favorite lens," Topping said. "It's called the Lensbaby. It's manual focus. That's part of the reason why shooting with it is a challenge; the camera isn't finding that sweet spot for me. And this lens creates a lot of blur. It has a very shallow depth of field, so it registers very small, precise effects. I couldn't tell from looking at the tiny pic in the camera monitor whether the pictures were working out, or not. Thankfully, with digital you just shoot 100 and you get the shot."

F Street Foto Gallery, upstairs from Swanlund's Camera, hosts 24 Hours, 24 Photographers Sept. 3 through 29.

more from the author

-

Nancy Tobin's CRy-Baby Installation at CR

- Feb 22, 2024

-

Truth Units

Bachrun LoMele's Burn Pile/The Andromeda Mirage at the Morris Graves

- Sep 7, 2023

-

Ruth Arietta's Illusory Interiors at Morris Graves Museum of Art

- Aug 10, 2023

- More »