|

COVER

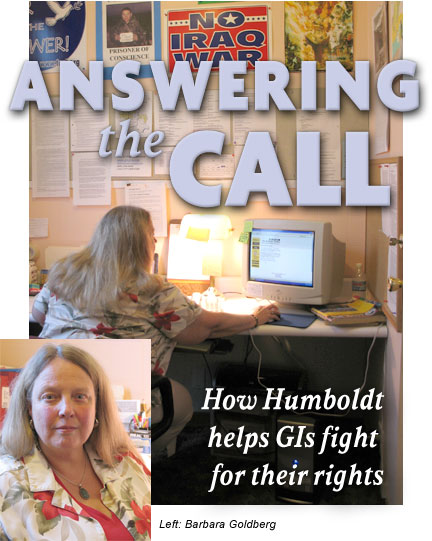

STORY| IN THE NEWS | PUBLISHER October 6, 2005

by WILLIAM

S. KOWINSKI

It's safe to say that most if not all the local volunteers who answer calls on the GI Rights Hotline have antiwar convictions. In interviews, several repeated the formula, "Ending war, one soldier at a time." But the actual work they do often turns out to be advocacy for individuals -- young men and women, teenagers, parents and spouses -- who may not fully share their beliefs, but who need help in their private battles against an overwhelming force: the military and political bureaucracy. Although some students have participated, most of the 11 current Hotline volunteers are adults with responsible positions in the community, and many have lived in Humboldt County for a long time. Goldberg, a resident for 35 years, teaches English at Humboldt State. She was there from the beginning. What the hotline does Shortly after 9/11/01, several hundred people attended a community meeting at the Bayside Grange to talk about what might happen next. They divided into small groups according to their concerns, and Goldberg and some others who'd done draft counseling in the Vietnam era met with mostly parents who were worried that the military draft might be revived. She later contacted the Central Committee for Conscientious Objectors (CCCO) in Oakland, an independent organization founded in 1948, with headquarters in Philadelphia. She asked if they would send someone to Humboldt to bring volunteers up to speed on draft law. The CCCO said they'd love to help but couldn't really spare anybody -- they were involved in another project that was growing so fast they were overwhelmed. It was the GI Rights Hotline, organized by CCCO but staffed by a coalition of six groups (the Center on Conscience and War in Washington, D.C., and Quaker House in Fayetteville, N.C., prominent among them) to respond to calls from people in the military who needed help with discharge requests, grievance procedures and other information about their rights and options. The Hotline started in 1995, but after 9/11 the volume increased so fast and so much, the existing network couldn't cope. Thousands of calls were going unanswered. "So as they told us their stories it just became clear that the most immediate and pressing need was for people to try to help those who were in the military and their families," Goldberg said. "They said if we would consider establishing a branch of the Hotline in Arcata, they'd come up and train us for that, and also provide the draft training we'd originally requested. So we took the training, we spent a couple of months studying the law and working on the practice cases the CCCO gave us, and on Martin Luther King's birthday in 2002, we started taking calls here." Three and a half years later, the Arcata group has handled some 11,000 calls. "They do the largest number of calls of any group that doesn't have paid staff -- about 10 percent of the calls for the whole network," said Steve Morse, Program Director for CCCO in Oakland. "With only volunteers, they take on a lot of calls with a lot of enthusiasm." That's been important because the network has fielded more calls every year, a total of some 32,000 last year. The war in Afghanistan, the invasion of Iraq, the call-up of reserve and National Guard units, the extended retentions and re-deployments, the frenzy of recruiters trying to make elusive quotas -- all resulted in sudden jumps in calls, and new problems for the Hotline volunteers to confront. Callers use an 800 number, and are routed to each Hotline office according to where the call originates. Arcata handles nine states -- Montana, Idaho, Utah, Wyoming, Nevada, Kansas, Missouri, Iowa and Arkansas -- in addition to northern California. Though volunteers work mostly in the evenings, an answering machine takes messages and provides information on when counselors will be there. There's a local number as well, and Arcata also gets all the calls from cell phones with area code 707 numbers. "These days soldiers take their cell phones with them," Goldberg explained," and if they have a local number and call the hot line, we get them, no matter where they are ... We haven't broken the calls out by area, but every shift somebody local will have called. I'm thinking at least 10 percent of the calls we take are local." "We get people coming into the office, too," said Rick Campos, member of the Vietnam Veterans for Peace and the first veteran to work the phones here (there are three now). "And we do a lot of outreach, letting people know we're here and talking about their concerns." What are those concerns? Who is calling and what are they calling about? Men and women now on active duty call from military bases, or from home when they're on leave, or Absent Without Leave (AWOL). "There are a lot of military bases in our states -- in Missouri, Arkansas especially," Campos said. "We used to get Oregon calls before they started a Hotline office up there, and Alaska. There are a couple of big bases in Alaska. We helped a lot of Marines in Eugene." Many calls are from young people -- 18 or 19 -- who didn't understand what they were getting into when they joined the armed forces. "Sometimes they go into it with false expectations," said Helen Jones, an Arcata volunteer and a lawyer with experience in military law. "They join because the recruiters promise them they can get money for school. The recruiters don't emphasize the going to war and killing people part." "We've had a huge increase in calls from people who get to basic training, and are depressed and don't really know why," Goldberg said. Sometimes the catalyst is clear: when they're faced with shouting "Kill! Kill! Kill!" and stabbing a bayonet into a human-shaped dummy or shooting at a target in human form. "Yes, they all know that they might have to kill somebody, but they were thinking about bringing freedom to Iraq, not developing this kind of murderous instinct. They just freak out -- this training is not what they think their mission is." Though they might realize they'd been naïve, the impact can be devastating, according to Goldberg and other counselors. Some can't function as a soldier at all after that. Others begin thinking about what they can morally justify -- perhaps for the first time in their lives. They need to talk to someone who understands what they're going through, and can help them sort it out. These cases might lead to attempts to get a discharge or to a conscientious objector application -- both very difficult processes, made much worse, according to Morse, because the military often doesn't abide by its own rules. "They drag out the process, they deny requests for reasons that aren't in the regulations. They organize campaigns against people who apply for C.O. -- they try to isolate them, ridicule and sometimes harass them, and sometimes put them in physical danger." These situations are familiar from at least the Vietnam era, but there are aspects of the Iraq era that are new: soldiers being kept in Iraq longer than their original rotation and sent back for additional tours, including some forced to stay past their original enlistment time. And then there are the unusual and even unprecedented deployments of reserve and National Guard. Volunteers hear about the ensuing problems on the Hotline. "I've talked to a lot of people who are back from a second and even a third deployment to Iraq," Goldberg said. "A number of them say, I just can't go back. You have no idea what's going on over there, and I just can't do it anymore." "When you talk to these guys who have been in the military awhile, and they always sort of thought of someone who objects to war as a pansy who won't stand up and fight for their freedom, and now they realize what modern warfare really means, and it's very different than the things they believe in." Being sent to Iraq was especially traumatic for reserve and National Guard members (which caused a big increase in hotline calls), as it was for local Coast Guard units (which brought even more calls to the Arcata office.) "Many Coast Guard members here were troubled by their deployment because they joined to protect the local community and respond to disasters," Goldberg remembers. When hurricane Katrina devastated the Gulf coast, more than a third of Louisiana's National Guard was in Iraq, and nearly half of Mississippi's, along with much of their equipment needed for rescue work. "People realize now that the National Guard may not be here to help them out," Campos observed. "That made the biggest antiwar statement yet, bigger than anything else Bush could have done."

But much of the work the Hotline volunteers find themselves doing has little directly to do with anyone opposing this or any other war. "We don't just get anti-war people," Campos said, "though we get a lot of them. We get a lot of people who are getting screwed by the military." Right: Hotline

volunteers. As a veteran, stories of military mistreatment and injustice aren't new to Campos (and other volunteers say they're grateful to have veterans who know the system from experience.) But this aspect was new to volunteers like Goldberg, who hadn't encountered its full range until they began hearing from soldiers and their families on the Hotline. Goldberg said she heard stories of "family hardships that just unimaginable. Reservists who are losing their homes, whose marriages are falling apart, whose lives are falling apart, with these continuous deployments. People with very sick parents, with spouses that are having serious mental problems, children that aren't properly cared for, a whole range of things -- and the military is completely unresponsive to their needs. They're just coming up against a brick wall." Other common problems are service-related injuries and illnesses. Goldberg has handled cases ranging from helping a soldier get a discharge and continuing medical care coverage for a knee badly injury on duty, to an ongoing case of a man with a history of psychological problems who was convinced by a recruiter to go off his meds and not mention his illnesses when he signed up, and whose symptoms predictably returned after his enlistment began. He is now struggling to get treatment and get out. Though these cases can be drawn out over months, sometimes the result is dramatic. Goldberg once got a call from a soldier who was back home, AWOL. At his base he'd been having seizures, and because he'd been an emergency medical technician before he was in the military, he knew this meant something serious. "He kept reporting to sick bay and saying, `This is very serious, I need to see a doctor,' but they just put him on a list. He knew he needed help right away so he went AWOL, and saw a neurologist in his hometown who told him he had a brain tumor." Now he had a diagnosis, but he was also AWOL, so he called the Hotline for help. "A lot of what we did was enable his civilian physician to just talk with the military physician, because you're not sick until the military says you're sick," Goldberg said. There was also a long legal process because he'd gone AWOL, and "a lot of trauma for the family and the young man." But if he hadn't called the Hotline, he would have been arrested for being AWOL and with the diagnosis ignored, "Hhe probably would have died in the brig." Being mistreated is as surprising to many young people in the military as learning about it was for Goldberg. "They're always told, we're a team, we're a family, but if you're not functioning a hundred percent the way they need you to, the military can be a harsh place. That's not to say that some people don't have good experiences with the military, but tens of thousands of people who call the hotline every year have a different experience." Though several of the Hotline volunteers have professional knowledge and special experience in one area or another, they are careful not to offer legal or medical advice. They will put callers in touch with physicians or specialists in military law, and all too often they must refer callers to suicide counselors. But they do offer information, and much of it comes from other callers. "One of the unique things about how the Hotline works," Goldberg said, "is that the people we help call us back and tell us how it went. So we often learn exactly what's happening at a particular base in a particular situation. We let people know what their rights and responsibilities are, but we can also tell them what we've learned that can give them a sense of what might happen." Sometimes there's nothing they can do but listen. "We talk to women whose husband are deployed who are just so frightened and depressed," Goldberg said. "They just want to know, is there anything we can do to get them home? Often there's not, but at least there's somebody here listening to them. And that becomes an important part of the work." Not only are the Arcata counselors an all-volunteer army, they actually pay to work for the Hotline. "We pay the 800 charges for all the calls we get," Goldberg explained. "And we pay for this office space and materials we send out locally. We all pay something out of our pockets to support this." Apart from a $5,000 grant from the Andrea Wagner Foundation and support from the local Veterans for Peace organization, they depend on donations and funds they can raise from the local community. But there are other rewards. "Even when I feel like I've been beaten up, when I go home from a night on the Hotline I always feel that it really mattered I was here," Goldberg said. "That's kept me coming back. It's very human contact with someone in need, so it's really satisfying work." William S. Kowinski is a writer in Arcata. His portal on the web is dreamingup.blogspot.com Recruiting KidsDR. FRED ADLER IS ANOTHER EARLY VOLUNTEER still taking shifts on the Hotline in Arcata. He and his wife, Carol Cruickshank, are also involved in an ongoing attempt by six members of the Humboldt Friends Meeting, a Quaker group, to visit prisoners of the war on terror inside the Guantanamo Bay Prison in Cuba. As an emergency room physician at Redwood Hospital in Fortuna and other area hospitals who also practices at the K'ima:w Medical Center in Hoopa, Adler keeps an eye on the Hotline's medical cases. Though the conversation at the Peace and Justice Center started with Barbara Goldberg reviewing some current medical cases with Adler, it soon focused on a jump in the number of calls from teenagers 17 and even 16 years old who had responded to the increasing recruitment efforts in high schools, and were afraid it was already too late for them to get out of the military. In most cases their fears are groundless, but that's not what their recruiters allegedly say. "We've been getting a lot of calls from young people with amazing stories about what recruiters are telling them about changing their minds before they go into the military," Goldberg said, "They're told if they don't report for duty on the assigned date that they'll be shot as traitors, or that they'll face two years in prison. They get so frightened they go down and sign up because they don't feel they have any other option." These high school students are part of the increasingly notorious Delayed Entry Program. They join the program while they're still in high school, then begin training the summer after graduation. But contrary to what they're sometimes told, they can change their minds. "I'm glad they updated the website [http://www.girights.org] on this," Adler said. "The new description of the delayed entry program is really good. It tells them that they aren't really in yet, until they go through basic training and really go into the military. When in doubt, just don't go." "Yes, they aren't really in the military until they've been issued a weapon and a uniform and they're getting paid," Goldberg added. Adler mentioned that recruiters tell students who want out of the program that they'll never get a job with this on their record, or they're told to wait until after they've officially signed up in the military before opting out but that's actually too late. "But even if they've done basic but not advanced training, and they're under 18, they still have some pretty good avenues out," Adler said. Goldberg was now hearing about another program, designed for even younger students. "They're trying a new recruitment retention program now," she said. "I've only had one case so far, but I've heard of others. They sign the kids up when they're 16, send them to basic between their junior and senior years of high school. It's not regular basic more like an Outward Bound experience, like summer camp. Then they go to advanced training the summer after graduation. Most will turn 18 by then, and they've completed their whole military training. So they're cut off from any easy avenues for leaving." "There are so many tricks, and they seem to be targeting younger and younger," Goldberg added. "And these kids are very vulnerable, they don't know what to do with their futures." Recruiters have several formidable weapons, including some that are akin to stealth technology. One is the Armed Forced Vocational Aptitude Battery, the set of aptitude tests that many high school students take routinely. But it's not just guidance counselors who get the results. It's the military recruiters. Armed with test results, recruiters can tailor their pitch to a student's interests, by talking about the nursing programs, computer programming or aircraft maintenance, and mentioning that their test scores will probably get them right into the program of their choice. (In fact, there are no guarantees; many troops on infantry duty in Iraq are specialists in other fields.) Even if the scores don't show any special aptitudes, the recruiter can use this information to dangle possibilities of travel and independence to young people who lack direction but are likely to want to get out of their parents' house. Information on individual students is also given to recruiters under a little known provision of the "No Child Left Behind" Act, a federal program to support education. "If parents don't sign a particular form," Campos said, "their child's name is given to military recruiters. The high schools are a real battleground right now, and a lot of kids are getting preyed on by the military recruiters." "They're preying on the poor person who want training," Adler said. "Now they're targeting Latinos, especially those who want to be American citizens. Something like 15 percent of the troops in Iraq aren't citizens." Military service puts them in the fast track for citizenship, but it is also another weapon to keep them in: some fear they'll be deported if they fail to complete their military commitment if any reason, including conscientious objection. "Fortunately, we've got immigration attorneys we work with," Goldberg said. "Now that enlistment is down in the black community, Latinos are being heavily recruited."

COVER

STORY| IN THE NEWS | PUBLISHER Comments? Write a letter! © Copyright 2005, North Coast Journal, Inc. |

Tales

of hardship

Tales

of hardship