|

IN THE NEWS | CALENDAR

by ARNO HOLSCHUH

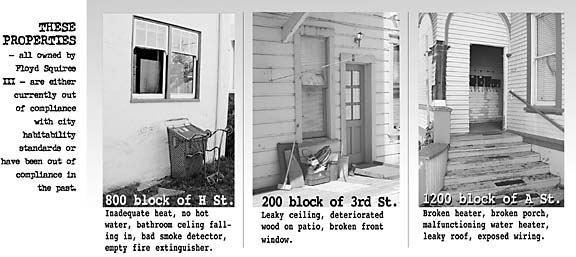

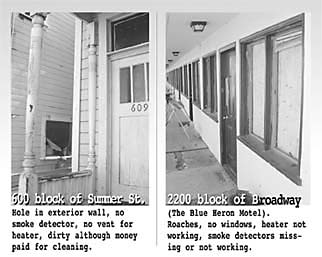

MALLOY CHAPELLE [photo above] WISHES she'd never seen the apartment, or ever heard of Floyd Squires III. When Squires, her prospective landlord, showed her the second-floor walkup in an old Victorian in midtown Eureka last summer, she thought it was reasonably cute if you could look beyond the empty Jack Daniels bottles the former tenant had left scattered around the floor. But her enthusiasm for the place and her relationship with Squires quickly soured. Simple maintenance issues blossomed into a court battle and ultimately an eviction. What's more, she believes she may have been exposed to potentially lethal carbon monoxide fumes for most of the winter. These days, Chapelle's possessions are in storage. She's living week-to-week in a run-down motel, just one step away from homelessness. She sits on her unmade bed, watching TV or looking out at the traffic droning along 101. How did Chapelle get from that Victorian flat in the 1800 block of C Street to the motel? The answer has to do, in part, with the landlord, Squires. Squires rents to a lot of people -- he owns 24 rental properties in Eureka, each subdivided into several individual units. Almost all the rentals are low-income, and many have been found to be in violation of basic housing standards at some point over the last 10 years. In a way, Squires is providing a public service. He rents to people that others tend to shy away from, keeping marginal tenants off the street. Of course, in some of his properties you have to be willing to put up with leaky roofs, roaches, fire hazards, exposed wiring, rotting stairs, busted windows, defective plumbing, faulty heaters or no heat at all. If you can think of a problem, one of Squires' properties has probably had it.

Descriptions are from City of Eureka Building Department files.

Several of Squires' tenants have complained to the authorities about the condition of their apartments, and some have been evicted soon after. Strictly speaking, kicking someone out because they complained -- called "retaliatory eviction" -- is illegal under California law. But Squires, who did not return several calls for this report, does well in court. Few tenants have won against him when fighting evictions. Squires knows the system. With around 20 years of experience under his belt as a landlord, he has frequently avoided timely repairs without being financially penalized. Enforcement of building codes on his properties eats up an immense amount of city resources but the violations continue. A tenant's rights advocate put it bluntly: "He provides unsafe housing." "I moved in during the summer of 2001 and everything was OK," Chapelle said. Sure, there were some issues -- the steps leading to her door were in need of repair, and there was a leak under the sink. But they were issues that Malloy Chapelle [in photo below left] was by and large willing to work around. ![[Photo of Malloy Chapelle]](cover0425-chapelle.jpg) That worked until last November when the Eureka winter started to fasten its cold, wet grip on the building. "When it got cold, we [in the building] started to have problems." That worked until last November when the Eureka winter started to fasten its cold, wet grip on the building. "When it got cold, we [in the building] started to have problems."

She learned that the family living below her wasn't using their heater--the Eureka Building Department would later confirm that the heater didn't work properly. They tried using space heaters, but the excessive electricity use would trip the circuit breakers. That was a chance they couldn't take, because the fuse box was locked in the garage. And when she started talking to the other tenants, she found out about other problems. There was exposed wiring, a dripping ceiling and some leaky plumbing. To Chapelle, however, the most glaring problem was the lack of a functional heater downstairs. "They were down there with no heat in the middle of winter," Chapelle said. When she saw the family's children bundled in jackets against the cold, she took it upon herself to do something. Chapelle was uncertain about what her rights under the law were, or how to best pursue them. So she called the number she had found on a flier from the Tenants Union of Humboldt County, a renters' rights group. A woman named Sarah Sherburn-Zimmer [in photo below right] answered the phone and suggested they hold a meeting with all the tenants in the building so that they could present Squires with a united front. "I went and met with her and everyone in the building on Nov. 28," Sherburn-Zimmer said. She was shocked at what she found; not just at the number of problems, but at the tenants' attitudes about their landlord. "Everyone was really afraid," she said. They were living in substandard conditions but didn't know what to do about it. ![[photo of Sarah Sherburn-Zinner]](cover0425-sarahS-Z.jpg) Sherburn-Zimmer suggested they try to make the situation work with Squires. After deciding what the most urgent repairs were, a letter was written Dec. 11, civil but firm in tone. It was signed by tenants living in five units in the building. Squires was reminded of his legal duty to maintain his rental properties to certain minimum standards of habitability, and told exactly what needed to be done. The tenants needed access to their fuse box; faulty heaters needed to be replaced in two units; the roof needed to be fixed. A timeframe of seven days was suggested for Squires to meet with tenants and discuss the repairs. Sherburn-Zimmer suggested they try to make the situation work with Squires. After deciding what the most urgent repairs were, a letter was written Dec. 11, civil but firm in tone. It was signed by tenants living in five units in the building. Squires was reminded of his legal duty to maintain his rental properties to certain minimum standards of habitability, and told exactly what needed to be done. The tenants needed access to their fuse box; faulty heaters needed to be replaced in two units; the roof needed to be fixed. A timeframe of seven days was suggested for Squires to meet with tenants and discuss the repairs.

Seven days passed and nothing happened; no repairs were made. Christmas came and went, as did New Year's, with no action. In early January, Chapelle decided it was time to take a new tack. This time she didn't write a letter or contact Squires directly. Instead, she called the building department. Her Jan. 7 call brought a building inspector to the house the next day. He was treated to a guided tour of the building by Chapelle and uncovered 15 violations of building codes. The Eureka Building Department sent a letter Jan. 10 advising Squires that the house was considered to be a public nuisance and he needed to take out building permits for the repairs within five days. Floyd Squires is well-known in the Eureka Building Department. The landlord has frequently run afoul of the department over the last 10 years, accumulating a stack of correspondence more than a foot thick. Often, violations are found but no building permit is taken out for the repair, making a second notice necessary. More than once, the city threatened to file civil suits against him to force him to make repairs. Squires maintains he's a responsible landlord. In a letter dated Dec. 23, 1997, he said that he tries "very hard to keep our properties in excellent condition." The blame, Floyd maintains, rests with the tenants. When informed in September 1997 that one of his buildings was out of compliance -- roaches, broken windows, rotted flooring and "general dilapidation" were cited -- he responded that, "It is not dilapidation. It is TENANT ABUSE." "Unfortunately," the letter explains, "I rented to [the tenants] without fully checking their references, and after I did find out about how [they] had destroyed prior apartments, I served [them] with an eviction notice. So they started tearing up my apartment." The letter even says that there were no insects in the apartment aside from those collected by the tenants. The pattern appears frequently in his files: One letter from Squires states that tenants who had complained about their lack of electricity were actually stealing his electricity. Another letter claims a tenant who had complained about lack of heating was in reality breaking out windows and tearing the building apart. Another tenant, this one with a leaky roof, was really just "out to cause me problems." In another building with the same problem, the tenant was simply "lying," Squires writes, and was being held on $125,000 bail. A tenant brazen enough to ask for a functioning toilet and heater, "is on her way back to State Prison for drugs." After dismissing the tenants as delusional, Squires then often goes on to directly contradict the results of the building department's inspection. Take a July 2001 inspection that revealed that one of Squires' properties had a heater with a faulty thermostat. Squires' response? "There is only one heater and it works fine. There is no problem with the thermostat." Such a response "doesn't stop our processes," said Eureka building official Mike Knight. "Floyd has to find a way to make those repairs." Knight said building inspectors have the same procedure, no matter who the landlord is: After getting a complaint, they conduct an inspection, document any violations, notify the landlord and try to bring him or her into compliance with the law. In the case of Squires, it has not been unusual for him to take months to respond to violation notices from city hall. Nonetheless, Knight said that the process has often worked with Squires. "Floyd may not always react in the timeframes the tenants would want and perhaps not as quick as I would like to see, but he has been reasonably responsive to phone calls and letters." And while a number of his buildings appear dilapidated, Squires does eventually do repairs -- particularly when threatened with a lawsuit. Others in the Eureka city government were more critical than Knight. Attorney Brad Fuller said that in the four years he has had his job, he has seen "a hugely disproportionate amount of time spent on Floyd Squires and his properties." "He wouldn't keep coming to the top of my pile with requests for last-chance notices and possible filings of complaints in court for being a public nuisance if he wasn't doing something wrong. It happens way too much." The city of Eureka, Fuller explained, has a "complaint-driven, compliance-oriented" code enforcement program. Inspections only happen when there are complaints, and the enforcement measures are designed to move a landlord toward compliance, not penalize him. The system works well most of the time. It's only occasionally, as in the case of Squires, that it falters, Fuller said. "And I don't know what kind of system would work perfectly," Fuller added. "We continue to search for the tool to convince him to maintain his properties," Fuller continued. One option, he said, would be for the city to sue Squires for using unfair business practices. "The law is against anyone who knowingly violates the law in order to gain an unfair advantage over his competitors," Fuller said. If Squires skirts the law while other landlords comply with legally required maintenance on their property, he might be legally vulnerable, Fuller said. "I think this is something that should be considered with someone like Floyd Squires." "So on Jan. 8, after the inspector came, I found a red notice on my door," Chapelle said. She was behind on her rent, it said, and needed to get in touch with her landlord. Chapelle knew she owed Squires money. When she moved in, she didn't have enough cash for a security deposit. She said Squires agreed to let her pay it at a later date. So she called Squires' home and talked to his wife, Betty. Chapelle said she was told she should not have involved herself in the affairs of other tenants -- specifically the family below. "I said it was my business as a human being to get involved when I see little kids bundled against the cold," Chapelle said. "I told her I had been the one who called the building department." The next day she received a notice to pay the money Squires said she owed him -- $600 -- or get out. She tried to make arrangements to pay Squires. "I talked to him the next day and he said he didn't want the money. He wanted his property back." In the meantime, repairs were begun on the building. Squires worked on the leaky roof and fixed the heaters in two of the apartments. The most urgent problems were dealt with. But the eviction proceedings against Chapelle continued. Retaliatory eviction is illegal under state law, but it happens all the time, said Jan Turner [in photo below left] , staff attorney with Legal Services of Northern California. Her group represents the poor and the elderly, and she's seen lots of retaliatory evictions by landlords who never get caught. ![[photo of Jan Turner]](cover0425-Turner.jpg) "If a tenant has complained or exercised his or her legal rights, the landlord is not supposed to be able to evict without good cause," she said. "That section is violated extremely frequently." "If a tenant has complained or exercised his or her legal rights, the landlord is not supposed to be able to evict without good cause," she said. "That section is violated extremely frequently."

Sherburn-Zimmer said landlords act with relative impunity because they are better equipped for a court battle. "From all the renters I have talked to, I have gotten the impression that judges are more likely to believe a landlord. That's especially true when you have a well-dressed landlord against a not-so-well spoken tenant who can be pretty chaotic." "Going to court hasn't been very productive for most tenants," Sherburn-Zimmer admitted. That is especially the case with Squires' tenants, she said, who tend to be easy to best in court. She said that's partly because they are usually living on the margins of poverty and are too poor to afford an attorney; and also because some of them suffer from a mental disability -- like Chapelle, who is on permanent disability insurance for post-traumatic stress disorder. Six other tenants interviewed were on disability insurance, two of them for mental illness. Chapelle lost her fight against eviction. During the Jan. 31 court proceeding, Squires convinced the judge that he had acted in good faith. Chapelle wasn't an activist, he maintained, but a mentally ill drug addict who wouldn't pay her rent. A week later Chapelle was told to get out. By that time, there was another reason for her to leave the apartment. Throughout the winter, Chapelle had been getting headaches and feeling tired and out of sorts. For a long time, Chapelle paid the symptoms no mind -- at least she had heat. Then a friend in another of Squires' buildings told her about how his gas had been shut off because of a faulty heater. Chapelle called PG&E to check out her own heater in early February. The inspector from the gas company came out and found that there was indeed an improperly vented floor furnace that could well be allowing carbon monoxide fumes into her apartment. Carbon monoxide leaks are no joke. It's a building code violation where negligence can lead to death. It's happened before. In 1996, an improperly vented water heater killed two young men. According to the County Coroner's report, Chris Dixon, 17, and Clarence Lee Moore, 20, had apparently left the hot water running so they could do the dishes at their apartment in the 900 block of F Street. Moore was sitting on the couch with the television on and Dixon was in the bed when his parents came by to check up on him and found both men dead. Dixon, who had only recently moved out of his family home, had just gotten his high school equivalency diploma and was showing an interest in computer programming. "It was the kind of thing where we thought, OK, now he can move out," the youth's father, Paul Dixon, recalled. But the young man had unwittingly moved into a bad situation -- very bad. When the fire department showed up and tested the air for carbon monoxide, their meters went off the scale. The level of the gas in the apartment's air was enough to kill most people in less than an hour. When the elder Dixon climbed into the apartment through an open window to unlock the door from inside, he was immediately affected by the gas, becoming disoriented and fumbling with the door knob. The father, who supervises a construction company and is familiar with building codes, places the blame squarely on the landlord. In this case, that landlord was Floyd Squires II -- father of Floyd Squires III, Chapelle's landlord. [A wrongful death lawsuit was filed by Dixon's family. The case was settled out of court.] For Dixon, it's amazing that problems with improperly vented heating appliances have cropped up at the son's properties in the years following this tragedy. "It's like he's just waiting for another death to happen. What are they going to do then?" Chapelle's eviction came not long after she found out about the faulty heater. With nowhere else to turn, she ended up at the motel. Now she's worse off than she was when she first started renting from Squires. An eviction on anyone's record is a black eye when landlords are looking at potential renters. Making things more dire, she recently lost her Section 8 housing assistance, which brought in $283 a month. That leaves her with only a monthly $750 Social Security disability insurance check. It is not clear why Chapelle lost the Section 8 money; she plans to discuss the matter soon with the Housing Authority for the city of Eureka. It is clear, however, that after successfully evicting Chapelle, the Squires wrote a letter to the Housing Authority requesting that Chapelle be removed from public assistance. "Some people are very deserving and needy," the letter begins. It goes on to note that there are a few bad apples -- like Malloy Chapelle. The letter claims Chapelle failed to pay rent, used drugs and disturbed the other tenants -- all of which Chapelle denies. She was also a bad housekeeper, used foul language and hung signs in her window declaring Floyd Squires a "slum king," the letter said. The city eventually could file suit against Squires and the tenants union might organize his renters, but that's not going to help Chapelle. She continues to look for a place to live on her limited income, so far for naught. If she faces one unexpected expense -- if her dog needs to go to the vet or she needs to go to the doctor, for example -- she fears she will be unable to make her week's rent and will be thrown out of her bleak motel room. It's all the more bitter because she tried to work within the system, first by contacting Squires, then the city, then by pleading her case in court. For Chapelle, the message from the system is quite clear. "Everybody thinks I'm a throw-away person," she said, slumped on her bed. "Unwanted."

IN THE NEWS | CALENDAR Comments? E-mail the Journal: [email protected]

© Copyright 2002, North Coast Journal, Inc. |