This Season in Ashland

August Wilson and a new playwright explore emotions of two eras at OSF

By Margaret Thomas Kelso and William S. Kowinski[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Even before Ma Rainey's Black Bottom made his name on Broadway, playwright August Wilson was intent on avoiding the all-too-common fate of a one-play career. For that crucial second play he also gave himself a specific challenge: to follow the eccentric structure and multiple focus of Ma Rainey with a more conventional narrative centered on a single complex character. So from experiences and characteristics of his step-father and a near neighbor, and from his own home-run-hitting prowess as a teenager, Wilson created Troy Maxson, a baseball legend in the Negro League kept out of the segregated major leagues until he was too old, so that at the age of 53 in 1957, he works for the city of Pittsburgh collecting garbage.

The resulting play was Fences, which earned Wilson his first Pulitzer, Tony award and other prizes in 1987, and has been his most popular play ever since (though it was never his favorite). It's scheduled for a Broadway revival in the fall, and the Oregon Shakespeare Festival production is on stage in Ashland now.

From that first production, this story of a husband and father, his wife, his sons and brother, and their relationships to each other and to their own individuality, was recognized for its universal themes. But the universal is best expressed in the particular — which is one of those truisms that's often true. Certainly Troy Maxson's story as it is gradually revealed expresses aspects of the African American experience. Yet there are other specifics that resonated for me when I saw the OSF production.

I recognized the 1950s, especially among the working/lower middle class, and specifically in Pittsburgh. I grew up some 30 miles from where August Wilson did, at about the same time (we were both pre-teens in 1957). So when Troy talks about hitting a home run and says, "You can kiss it goodbye," I recognized the locution of a particular Pittsburgh Pirates broadcaster of that era.

Yet despite our proximities, the worlds of Wilson's plays were mostly foreign to me — except this one. The terms of the respect Troy demands from his son are specifically familiar from the black family next door, and a boy I grew up with. I heard Troy's speeches about not wasting time on anything other than preparing to make a living from fathers of many ethnicities, including my own.

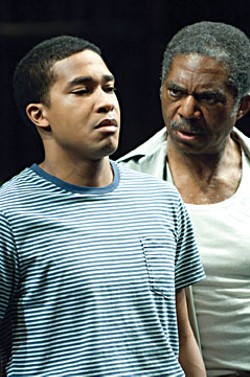

Charles Robinson as Troy Maxson accentuated this familiarity. His relentless insistence on dominating by having the answer for everything, combined with his compact, wiry frame, reminded me of many 1950s fathers. Yet casting him as Troy was risky. Wilson describes the character as "a large man," and from James Earl Jones on, large men have played him in the first generation of productions while Wilson was alive. This can be important to Troy's character and the play's most dramatic moments: the contrast between Troy's largeness of body and need, and the constrictions he rebels against, while in other ways he continues to bear the fate and the heavy responsibilities that define him. It's also important to the white societal fear and other images associated with big black men.

So some of those dramatic moments and motivations seem less than they could be, and while the efficient naturalism of this production has its virtues, there are mythic qualities of Troy that go missing. Still, it's certainly worth taking some trouble to see. Director Leah Gardiner makes full use of the stage to keep the eye involved, as the ear is entranced by Wilson's trademark stage poetry. Robinson performs very well, as do the other actors (Shona Tucker as his wife, Rose; Josiah Phillips as his friend, Bono; Kevin Kenerly and Cameron Knight as his sons, Lyons and Cory; G. Valmont Thomas as his brother, Gabriel; and Catiana Graham and Dominique Moore alternating as his daughter, Raynell). They speak the rhythms of Wilson's words, which together with the backyard set by Scott Bradley and lighting by Dawn Chiang — naturalistic and mythic at the same time — create stage magic.

But there's not much time (Fences closes July 6) and not many opportunities (after this week I count just 15 more performances). Also closing soon at OSF (on June 20) is a new play, Welcome Home, Jenny Sutter. In our weekend in Ashland I had a time conflict with another play (I'll be writing about three more in coming weeks) but fortunately my partner, the playwright, director, teacher and now drama critic Margaret Thomas Kelso saw it and filed this report:

Welcome Home,*Jenny Sutter*by Julie Marie Myatt joins a long line of stories about soldiers returning from war, dating back to Homer's Odyssey. And like Ulysses, Jenny Sutter does not take a direct path home. But instead of Calypso's island, Iraq war veteran Jenny detours by way of Slab City, Calif. (an actual abandoned Marine base populated by squatters), in her own odyssey to find herself before reconnecting with her family. Unlike Ulysses, she is coming home injured: She suffers from PTSD, survivor's guilt and an amputated leg. And as a woman, she faces greater expectations to emotionally reunite with her children. The play asks: Can she heal herself enough to be able to face the rest of the journey home?

Approximately 200,000 women have served in Iraq and Afghanistan so far, and more of them have faced hostile fire and resulting injuries than women in the military ever before.

The director, Jessica Thebus, discovered the perfect tone for the piece: amusing, gritty and without a trace of sentimentality. The performances are all strong. Gwendolyn Mulamba plays an acerbic and ironic Jenny, while Kate Mulligan as Lou, a professional itinerant trying to give up her many addictions, is an upbeat foil for the laconic Jenny. Other residents of the slabs are Buddy, Lou's sometimes boyfriend/preacher (skillfully played by David Kelly); Cheryl, Lou's hairdresser/therapist (K.T. Vogt); and Donald, an emotionally damaged cipher. Gregory Linington's deft performance prevents this character from sliding into romanticism.

Richard Hay created a simple set that serves flawlessly while maintaining a bit of magic in the scene transitions that OSF does so well. Allen Lee Hughes's lighting not only supports the action and mood but creates locales. Except for several extended lifeless scenes, the direction was skillful and sensitive, honoring the pain, celebrating survival and finding the humor in a challenging situation.

More by William S. Kowinski

-

TV or Not TV?

A Comic Dilemma at NCRT

- Sep 25, 2014

-

Unequivocal Success

Shakespeare in trouble at Redwood Curtain

- Sep 11, 2014

-

A Midsummer Night's Stage

Magic worlds at Redwood Park

- Aug 14, 2014

- More »