The World Is Yours, Oyster Farmer

Or will be, if the Harbor District can open more of the bay for mariculture

By Heidi Walters[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

The oyster farmer stands in the stern of the small gray skiff, clear-eyed, a bit of smile on his wind-nipped, broad face. Weather's supposed to turn nasty, but he's just wearing waders over his jeans, a black cotton sweatshirt under his orange life vest, and a tan ball cap that doesn't cover his ears.

With one hand on the tiller, the other in his jeans pocket, the farmer guides the skiff up a shiny channel between slick mudflats in North Bay, the northern bulbous extension of Humboldt Bay that nudges against Arcata. Low tide. He tips his chin at the sights: a flock of black brandts, flying in low across the bay to land in a dark-green eelgrass patch and begin nibbling. Earlier, the loon by the dock, an uncommon, speckled apparition; must be migrating through.

He slows the skiff, gently nudges its prow into a mudflat, and water clinks against the metal hull. Spread out on the exposed bay bottom before the skiff is one of his company's oyster farms: rows upon rows of long ropes strung between short PVC pipes about a foot above the bay mud, with clumpy oblong shells woven into them every few inches. Algae and mud have coated everything in brown-green-gold, though here and there wink glimmers of pearly shell. It looks like a squat, murky vineyard. These were "planted" last fall, during a low tide, the farmer says. Though you can't see them from the boat, each of the shells attached to the ropes has tiny oysters growing all over it; the little oysters are called "spat," the big empty shell they've cemented themselves onto is called "cultch," and together they make "oyster seed." It'll be two years, about, before harvesters can come in here, during a high tide, and haul the ropes in to collect the heavy adult oyster clusters.

Back in the open water, the skiff heading deeper into the middle of the bay, rain replaces sun and a rising wind whips the water into an alarming chop. The farmer, still standing, looks unperturbed. In command of his world.

Surely, this is the life. Following the rhythm of the tides, the ocean flowing in, flowing out, in, out. Inhabiting a world of birds and seals. Producing a food for the sort of folks who care about where it comes from and how it's grown -- heck, not even able to keep up with their hunger.

A dream.

A dream, apparently, that few can afford. To hear this oyster farmer and others tell it, if you want to set up a new oyster farm on the bay -- or expand an existing one -- you'll need buckets of money and the perseverance of a gull choking down a starfish to complete the slow-going, complex multi-agency permitting and environmental review process.

Not that current or prospective farmers necessarily disagree with the regulations, he says.

"It's not the 1950s anymore; you don't get to do whatever you damned well please," says the farmer, whose name is Greg Dale.

As the southwest operations manager for Coast Seafoods, the biggest oyster grower on Humboldt Bay (and in California), Dale speaks from experience: Over a period of 10 years ending in 2007, in response to environmental concerns and increased regulatory pressures, Coast was forced to completely alter its harvest methods. It spent more than $1 million on permits and environmental reviews from at least nine local, state and federal agencies.

Coast could weather the expense. But smaller operators generally can't -- which is why, farmers say, there are only five growers on the bay using just 325 acres out of several thousand that could potentially support shellfish culturing.

The Humboldt Bay Harbor, Conservation and Recreation District has a plan to change that -- to create a business park, of sorts, for oyster farmers by identifying a host of new sites, vetting them as a group for environmental compliance and pre-permitting them for the same culture methods currently used on the bay. The district would take on the regulatory risk, in other words. Once it completes that work, probably by 2014, the new sites would be leased out through a bidding process. Last year, the Headwaters Fund awarded the district a $200,000 grant for the spendiest part of this project -- the permitting and review. It also had the district add a provision: a fee on top of the lease rate to squirrel away for future permitting costs. Now the district has to go identify those suitable sites.

The project has evoked cautious optimism from conservationists and created ripples of excitement among shellfish farmers and regulators alike -- locally, regionally, nationally. Oh, and listen. Hear that? It's the well-heeled, banging their empty plates on elegantly clothed tables, demanding more Humboldt Kumamotos.

People have harvested oysters from Humboldt Bay for as long as they have co-existed with the large, shallow, wasp-waisted estuary. Native people ate the small, metallic-tasting Olympias that grew naturally, albeit slowly, in the bay and sloughs. Then came the Gold Rush, and first the hungry new hordes gobbled up the Olympias in San Francisco's waters. Then they reached long for those in Humboldt and other remote bays, importing young stock back to cultivate in San Francisco Bay (where, by the early 1900s, the water was becoming so polluted by industrial and population growth that the native oyster fishery was again declining rapidly, forcing shellfish farmers to seek out other bays.)

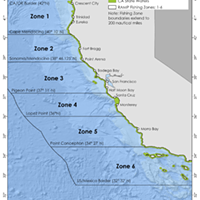

Humboldt's native Olympia oyster population, never that robust, collapsed. In the early 1950s Humboldt Bay shellfish farmers began cultivating the sweet Pacifics and, later, the mild, cucumbery Kumamotos, both originally from Japan. Coast Seafoods came in during that time, and by 1995 was the largest operator in Humboldt Bay, with 180 employees working with oysters grown on nearly 1,000 acres of the bay. Coast used a technique called bottom culture back then: placing oyster seed -- baby oysters attached to clean bits of oyster shell -- on the bay bottom in select sites, then, after about three years, barging in a hydraulic harvesting machine to shoot water over the oyster beds in ever-widening circles, exposing the oysters in the muck and flipping them onto a conveyor belt to be hauled in. If you've ever looked at old aerial photos, you may have noticed the odd "crop circle" marks that this method left in the North Bay. (That's where most of Humboldt Bay's shellfish farming occurs; South Bay, with its massive eelgrass beds, is dominated by a national wildlife refuge.)

In the mid-1990s, biologists and environmentalists began worrying that hydraulic dredge harvesting was hurting other habitat, including eelgrass beds which black brandt geese and other creatures rely on. They also didn't like Coast's habit of discarding shucked shells on the bay bottom, saying it created an uninhabitable pavement. And they protested Coast's killing of bat rays, the bottom-dwelling, shark-related creatures that would sweep through their bottom culture farms and eat up all the oysters. For years, Fish and Game had issued depredation permits to Coast to kill a certain number of bat rays.

The ensuing regulatory battle lasted a decade. Fish and Game revoked Coast's bat ray depredation permit. A cease-and-desist order from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in 2003 forced Coast to stop planting oysters in eelgrass habitats. Coast had to switch from bottom culture to long-line, rack-and-bag and other methods in which oysters grow suspended, and contained, in the water column above the bay bottom -- which ended dredging, and also put the oysters out of reach of the bat rays, eliminating the need to kill them. Coast also quit dumping empty shells back in the bay. The changes resulted in a reduction of its farmed area, over time, to 300 acres and of its workforce to about 50 employees. (Coast actually owns about 561 acres and leases about 3,385 acres in North Bay.)

In 2007, Coast completed the environmental review and permit procedures reflecting these changes. Today, Coast and other growers in the bay are required to avoid disturbing eelgrass beds, marine mammals, birds, spawning herring and salmonids and other fish and animals. They all are required to keep their permits updated and do water sampling once a month; Coast does it almost every day, said Dale. In addition, they must have their products -- whether imported for culturing or exported to other growers or markets -- regularly tested for disease and contamination.

Today, Humboldt Bay's five shellfish growers produce more oysters than anywhere else in California; some are consumed locally, but many are exported. In 2009, the California Legislature called Humboldt Bay the Oyster Capital of California. The Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch refers to Humboldt-grown oysters as a "best-choice" seafood because, among other things, the harvest of them has a low impact on the ecosystem and other habitats -- a nod, you could say, to those changes in farming practices.

Humboldt Bay also is the only estuary in California free of the diseases that have impacted shellfish elsewhere, and thus is the only place in the state certified to grow clam and oyster seed for export, said longtime local shellfish grower Ted Kuiper. (Kuiper has since retired and sold off his business and leases to other farmers. He now serves as a mentor for up-and-comers.) Three of Humboldt Bay's growers export seed to some 60 farms along the West Coast from British Columbia to Mexico.

Another fun fact: One oyster can filter 17 gallons of water a day. And you don't have to do anything other than put them out there in the water -- carefully, minding those other inhabitants -- where they can do their thing.

All it takes is "clean water, naturally occurring phytoplankton, tide energy and sunlight" to grow shellfish, said Kuiper.

And negotiating those permits. Shellfish farming takes place on public lands held in trust by the state of California. Locally, three entities -- the cities of Eureka and Arcata, and the harbor district -- handle the leasing of these trust lands to shellfish farmers. The farmers must get permits from their leasing authority, as well as from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the California Coastal Commission, the California Water Quality Control Board and Humboldt County. Their operations also must pass muster with a slew of local, state and federal entities, from the state Department of Fish and Game to the National Marine Fisheries Service.

Apparently, Kumamotos, Pacifics and their other introduced ilk are the posterchildren for exotic species we dare to like -- as long as there's none of that bat ray-killing, shell-paving, bottom-blasting, eelgrass-disturbing business going on to cultivate them, like in the old days. They sit out there in the bay in plastic mesh bags dangling from rebar racks, or attached like clusters of stone grapes to long ropes suspended between PVC pipes, or as tiny seed growing in racks floated under rafts. They're doing what they'd do, more or less, in the wild -- hanging out cemented to something, filtering water and growing plump, while flora, water birds and other fauna mingle among them. They don't interfere with the remnant populations of native Olympia oysters. Any new leases will have to be operated in the same way.

Harbor commissioner Mike Wilson, who worked with some Humboldt State University natural resources students on a study to see if expanding mariculture in the bay seemed feasible, said his team tried to root out conflicts that might flare up over an increase in farm leases.

"If there was going to be a conflict, we weren't even going to do this," Wilson said. "We couldn't find overt conflict. ... The perception of this industry has changed dramatically."

Some questions and concerns have been raised, however. Maggy Herbelin, a longtime bay health activist, said she hopes the district studies the carrying capacity -- that is, how much food is in the bay, and how many oysters it would take to deplete the food and starve out other creatures depending on it. Adam Wagschal, who is with the consulting firm that's working on the project for the harbor district, HT Harvey & Associates, said carrying capacity will be determined either by modeling or by observation. "One good thing about shellfish culture is it's not permanent," he said. "You can take it out," he said, if there appears to be a problem. He also noted that the ocean provides much of the food in the bay -- a pretty huge source.

Another concern to explore is whether adding more structures to the bay -- some farmers use rafts from which they hang racks full of seed -- might provide more platforms for certain predators.

Jennifer Kalt, the policy director for Humboldt Baykeeper, said as long as the project can be done so as not to impact eelgrass -- important for three listed salmonids and many other creatures -- she thinks it's "forward-thinking" in its goal to ease permit burdens as well as its consideration of the cumulative impacts of the new farms, "rather than reviewing each new farm one at a time."

There will also be the matter of fairness, if and when these new sites get permitted and are ready to be leased.

"There will be fierce bidding for these sites," said Kuiper. "The growers here are universally supportive of new people coming here. So I will be one of those individuals looking at this to ensure it's done fairly, that no company is able to receive more than 50 percent, say, of the areas that come up for bid. And that it all be done in public hearings."

[][][]

The harbor district's proposal scored higher than just about any project the Headwaters Fund Board had been presented with before.

"It's the kind of work we want to do," said Dawn Elsbree, coordinator of the Headwaters Fund. "We want to help business be able to grow, and aquaculture is an industry that makes sense for us here. We have a clean bay, it's an export business, and there was a direct link to job creation -- they could prove that for every additional acre they could grow shellfish in, it would create a specific number of jobs."

According to the district's proposal to the Headwaters Fund, the five growers employ 65 people full time and have a combined payroll of $1.4 million. They make a total of $6.2 million in gross sales per year. (They contribute in other ways to the local economy -- the annual Arcata Bay Oyster Festival can bring in more than $750,000 in a weekend.)

Harbor commissioner Wilson and his student team identified 2,647 acres that could potentially be used for shellfish farming and not harm eelgrass beds or other cohabitants of the bay. If even just a quarter of those acres got approved for new leases, that could add 33 more jobs to the local economy, according to Kuiper's calculations.

Another factor in the proposal's favor, said Wilson, was that the demand for oysters continues to rise. Local growers can't keep up, in fact, and sometimes have to buy oysters from elsewhere to meet their orders. Diane Windham, the regional aquaculture coordinator for the National Marine Fisheries Service's southwest region, said the United States still imports 85 percent of its seafood. Lately, she said, imports have dropped a bit, as international demand for shellfish and other seafood has increased, creating more competition. So, plenty of room, at least demand-wise, remains for more shellfish growers in the U.S..

Meanwhile, said Wilson, the prices for oysters don't fluctuate wildly. It seems a steady, growing business. "This is one of the low-hanging fruits on our list of priorities for economic development," he said.

But what really impressed the board members, said Elsbree, was the fact that here was a small cluster of growers on a bay perfect for growing shellfish -- and they wanted to let more farmers in to share their good fortune. Some of them even had employees itching to start their own farms. And they'd come together to promote the expansion idea, writing letters of support and speaking at meetings.

So, who are these benevolent people? And why are they so eager for competition?

The five growers on the bay range dramatically in size and type of operation. Some grow oysters. Some grow oysters and clams. Some grow seeds. Some have multiple employees. One is run by just one man. But one thing that becomes clear when you talk to the folks running these operations or working for them: It's like one big squishy family out there, with a lot of interdependence and a friendly hierarchy, and with most members having some sort of connection to patriarch Kuiper.

Coast Seafoods, the largest operator, grows adult oysters which it sells all over the world, and seed oysters and seed clams which it sells to growers locally and elsewhere on the West Coast, from Canada to Mexico. It recently received permits to expand its clam-seed operation.

Taylor Mariculture, the next largest operator in Humboldt Bay, is owned by the largest producer of farmed shellfish in North America, Taylor Shellfish, based in Washington state. In 2009, Taylor bought most of Ted Kuiper's seed business (established in 1981), and grows clam and oyster seeds which it sells locally and up and down the West Coast. Taylor plans to build a large seed nursery on the Samoa Peninsula and is undergoing the permitting and review for that now.

Humboldt Bay Oyster Co.'s Todd Van Herpe bought a portion of Kuiper's seed farm in 2002; he was Kuiper's manager for 10 years before that. Van Herpe grows medium-sized seed oysters to sell to other producers, and adult oysters that generally end up at trendy oyster bars in the San Francisco Bay Area, although he also sells some to Cafe Waterfront in Eureka and Murphy's Market in Cutten. Because he bought an existing business, Van Herpe didn't have to go through the initial, long permitting process.

North Bay Shellfish's Scott Sterner, who also grows mussels, started shellfish farming in the bay more than 30 years ago. He was the first to break into the local small-restaurant market, and today dominates it. He also does the Farmers' Market in Arcata.

And then there is the littlest guy on the bay, Aqua-Rodeo Farms, owned and operated by Sebastian Elrite. Elrite got his start in the oyster business in 1992, when he was a wildlife management student at Humboldt State, working first for North Bay and later for Kuiper Mariculture. In 1997, he started his own company on a 10-acre site he subleases from North Bay Shellfish, where he grows Pacific oysters with the rack-and-bag method: suspending them individually above the bay bottom in plastic mesh bags hung from rebar racks. Oysters raised this way can grow large and be nicely shaped, because they're not growing against other oysters, but the stress-free isolation can also produce weaker shells. Business has been tough; rising gas prices ate into the profits from his trips to the Ukiah Farmers' Market, and the outboard motor on his boat blew up, making it hard for him to farm at all. "I actually took a part-time job this winter," Elrite said. He works some days on Coast Seafoods' docks. "For me it's not about the money so much as being out there, and just enjoying the outdoor seasonality of it. Being at rhythm with nature, the tide. It's an interesting lifestyle, kind of romantic in a way."

From barely-making-it Aqua-Rodeo Farms to big Coast Seafoods, each farmer seems excited about the prospect of more space to farm on the bay, and even about more farmers.

"All the shellfish producers are friends and we all work together," said Dale, with Coast Seafoods. A former president of the California Aquaculture Association, and a recently elected harbor commissioner, Dale said he's pushed hard for years for something like this. "There've never been that many of us. There could be more."

Taylor Mariculture spokesperson Bill Dewey said if the harbor district's pre-permitting project succeeds and more farmers set up on the bay, that would likely increase the demand for Taylor seed.

"The more the merrier," said Todd Van Herpe. "I know one of the guys who works for me would like to have his own farm sometime."

Van Herpe also likes that the district's consultants will identify on maps likely locations for future restoration of the native Olympia oysters -- a particular passion of his, not for commercial reasons but just to "see if we can help nature get back to what it was." The project won't include the actual restoration.

Elrite hopes he can snap up a new lease of his own -- perhaps one less sensitive to rainfall closures. Right now, if half an inch of rain falls within 24 hours, he has to shut down for three days to allow any pollutants washed in from land to flush out. Some sites, such as Coast's which are closer to the bay entrance and get more ocean water flushing, don't shut down until more rain has fallen.

Meanwhile, Kuiper, though officially retired from the business, frequently takes wannabe Humboldt Bay oyster farmers on tours of local operations. He said he often fields calls from such folks. He used to tell them about the long, complex permitting process, and they'd slink away. These days he tells them to come have a look. And they're not all rookies.

One of these prospective new bay farmers is the Hog Island Oyster Co, established 29 years ago on Tomales Bay. The company raises more than 3 million oysters a year. Most of them supply Hog Island's three restaurants, including one in the Ferry Building in San Francisco, said co-founder of the company, John Finger, by phone recently. Finger already seems like part of the Humboldt family: He's known Kuiper for 30 years, and his company buys a lot of seed from Humboldt. When Finger, who's also a marine biologist, talks about wanting to grow adult oysters in Humboldt Bay, he sounds like a true foodie.

"If we grow a Pacific oyster up there it's different than what we grow here," he said. "Oysters vary on two things. One, on species -- like a wine grape, a varietal. And then there's place. Like terroir [for wine], there's merroir: Each bay has a different signature in terms of salinity, types of plankton, how much current there is. I think oysters are more about place than any other food -- it says something about a bay to be able to say it's healthy enough to grow shellfish in. Right there we're saying we care about the watershed."

It sounds a little trendy -- "merroir," indeed. But then, Humboldt County has not been shy about embracing this increased fetishizing of wine and food -- where it's grown, who farmed it, whether it suffered or hurt anything. It's a national affliction that makes shellfish farmers very happy, and that regulators are eager to encourage.

Even the National Marine Fisheries Service is getting on board. In June it launched a National Shellfish Initiative, a twofold policy to increase commercial and restoration-minded shellfish aquaculture.

At Coast Seafood's shellfish operation on Waterfront Drive, men in rubber aprons and slickers work in several sheds. In one, several are stringing oyster seeds -- clean mother half shells covered with tiny oysters -- onto yellow rope, splitting the rope first to wrap around the edges of each oyster seed, then pushing the attached seed along into a long mesh bag. When the bag is full, it's gathered shut and placed with a stack of others; they'll be hauled at low tide to Coast's lease in the bay, strung onto short pipes in rows and left to grow. In another shed, more men are sorting good oysters from cracked ones -- the damaged ones will be thrown back into the bay in bags where they can grow and heal. The soft clinking of shells in both rooms sounds like summer vacation -- hammock, wind chimes. Fast-moving hands indicate it is repetitive, hard work. In another shed, the ear-splitting slam of air hammers leaves no doubt of that. Here, earplug-wearing workers hold clusters of cemented-together adult oysters to the hammers, which look like violently vibrating big screwdrivers, to sheer them apart.

Back out on the water, rain dashing harder and waves growing deep, Greg Dale is bouncing the skiff hard across the farthest fetch of the bay, heading for the dock. "You have to be frickin' crazy to do this," he says, half-jokingly.

It's not for the greedy or fainthearted. Days colder than this March morning. Low tide-chasing, sometimes in the pitch-black night, to plant your oyster seeds. Weeks when you can't farm because rain has flushed pollutants into the bay so you've got to sit it out, give the ocean time to purge. Being at the mercy of your neighbors: people spraying chemicals in their yards, dogs pooping, cars dripping grease onto the pavement. Knowing you probably won't get stinkin' rich any time soon. And if you're Dale, the short-straw-drawing "meetings bitch" (as he puts it) at Coast Seafoods, you might swap all of that loveliness much of the time for the dreary, dry insides of too many board rooms.

But even for Dale -- when he gets a chance, say, to go out water sampling or to check on the shellfish -- and especially for smaller operators, the sort the harbor district envisions luring in, it really can be the good life. And getting rich doesn't have anything to do with it, says Van Herpe, the owner of Humboldt Bay Oyster Co.

"I gave up on career choices that were supposed to make you rich and famous," he said one day recently, as he prepared to deliver several sacks of oysters to Cafe Waterfront. "But I am rich in many ways. Here I am, 45 years old and doing the same stuff I was doing when I was 8 years old and running around in shorts and a T-shirt in the bayous of Texas catching fish and frogs."

Speaking of...

-

Indigenous Foodways, Wind Farm Opposition and Big Boats

Mar 31, 2024 -

Local Commercial Dungeness Crab Season to Open in January

Dec 20, 2023 -

Humboldt Bay Timeline

Oct 12, 2023 - More »

Comments (3)

Showing 1-3 of 3

more from the author

-

From the Journal Archives: When the Waters Rose in 1964

- Dec 26, 2019

-

Bigfoot Gets Real

- Feb 20, 2015

-

Danger at McCann

A kayaker's death has raised safety questions about low-water bridges

- Feb 19, 2015

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023