The Mormon Moment

Once-outcast religion in the spotlight as Romney accepts presidential nomination

By Scottie Lee Meyers[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Elder Mitchell Camper sits in his musty study room clutching his Mormon Missionary Handbook and reads aloud a few pages to his inseparable missionary companion. The wallet-sized booklet with 82 pages of small font disappears in his big hands. It's filled with so many rules that they seem to be spilling over the binding.

The missionaries can't roll up their sleeves and can't wear anything but sanctioned underwear. They can't have a "faddish" hairstyle. They can't read any book or watch any video that hasn't been approved by the church. They can't join clubs, musical groups or sports teams. If they play a team sport among themselves, they can't keep score. They can't call home, except for Christmas and Mother's Day. They can't flirt, and they sure as hell heck can't be alone with women. They're not the kind of guys you'd want to get a beer with; they can't drink alcohol. There's another rule too: They can't be without the rulebook.

As I prepare to spend a day with these ambassadors of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints -- the full name Mormons prefer -- I try to be on my best behavior too. I tuck in my shirt and try not to curse. But I'm having a hard time at it.

Mormons have now famously conquered Broadway, talk radio and reality TV. America is having a Mormon moment. And that moment is brought to you largely by Mitt Romney, who took the stage at the Republican National Convention last week in Tampa and became the first Mormon to accept the party's presidential nomination. Romney has been loosening his tie lately when it comes to his faith. In an effort to present a warmer version of himself, Romney recently invited reporters to church. The attention is making some Mormons nervous. As the November election nears, church followers celebrate their Jackie Robinson moment while white-knuckling Romney's potential gaffes, afraid the words and actions of one man could come to represent the entire church.

Mormonism was literally pulled out of Joseph Smith's hat. In 1827 Smith was a 25-year-old New Yorker who made a living using psychic powers to find treasure. According to church teachings, an angel asked him to retrieve golden plates buried in the hills of upstate New York. An unknown language was engraved on the plates, and Smith deciphered it by reading reflections in a seer stone at the bottom of his hat. Smith's transcriptions became the Book of Mormon, and the text remains the cornerstone of the religion to this day.

Driven from state to state as the religion grew, Mormons have had an uneasy history -- not just with polygamy, which the church officially abandoned more than a century ago, but with a worldview that sometimes seems locked in the 1800s. The church didn't allow blacks into the priesthood until 1978. Women still aren't allowed. And gays? In 2008, Mormons contributed more than $20 million to passing California's Proposition 8, a gay marriage ban still being contested in the courts. The church was by far the biggest donor, contributing more than half of the $40 million aimed at preventing gay people from marrying. And the church's clout is spreading worldwide. Today Mormonism is the fastest growing religion in the Western Hemisphere with more than 14 million members worldwide, and more than 6 million here in the U.S., according to the church. Globally, there are now more Mormons than Jews. And missionaries like those who roam through Arcata and Eureka help spread the word.

You probably know the Mormons as the guys walking in pairs around town in their white dress shirts and skinny ties, waving and smiling as you walk or drive by. Like the Poem Store woman, the backwards-running man, and the mustachioed accordion player, the Mormon missionaries have become small-town fixtures in their constant visibility. I've always wondered about that poem woman -- what does motivate someone to barter with poetry she types on a street corner? -- and I've had that same faintly voyeuristic fascination with the Mormons. So I embedded with Elder Mitchell Camper and Elder Cory Goynes for a day to see what it's like to be a man on a mission.

[][][][]

It's 6:20 a.m. when I arrive at the missionaries' H Street apartment in Arcata. I don't have to check my notes to see which unit they live in because only one light shines in the complex, and there's a picture of Jesus in the window.

The missionaries, called elders by the church, come out wearing athletic gear and running shoes. It's time for their mandatory exercises -- 30 minutes every morning, save Sunday. Elder Goynes checks his watch and sees that the minute hand points straight down. "Time to go," he says, and we jog out into the Arcata dawn, a produce-aisle mist falling around us.

We circle the Arcata Marsh, and return to the elders' small apartment just before 7 a.m. The place has a college-student feel, occupied by young men too frugal for matching furniture, decorated with posters tacked onto the walls. There are differences, though. The posters depict Jesus, Joseph Smith and biblical scenes, not Bob Marley. The beds have been taken out of the bedrooms and put into the living room, where the men sleep; the bedrooms have been converted into study rooms. There's no beer in the fridge, no TV on the stand and no magazines on the counter -- all are forbidden.

The elders clean up, chomp Pop-Tarts and make a church-sanctioned call on a smartphone with Jesus-themed wallpaper. They dress in their dark slacks and white shirts, complete with a black nametag on the left shirt pocket. They call this clothing the armor of God. The tops of their notorious underwear -- intended to provide "protection against temptation and evil" --are visible around their necklines and biceps. The undergarments are nothing more than white boxer shorts and a separate undershirt. The elders love ties, especially Elder Camper, who has more than 50 of them dangling neatly in his closet. "It's our only opportunity for individuality."

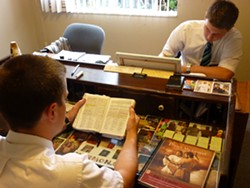

At 8 a.m., they start their mandatory two hours of study. In the center of the room are two desks, pushed together and facing each other. The whiteboard on the wall lists their long-term schedule and their personal goals. Elder Goynes is striving to more effectively use Facebook to reach out to people. (Our region is one of seven missions in the world that allows missionaries to use social media.) He also wants to deliver more meaningful prayers and keep better records. Elder Camper's goals look like a red-Sharpie haiku: Be less condemning, use less words, silence.

As always with the missionaries, they start with a prayer. The men go to their knees, fold their hands and close their eyes. Elder Goynes leads the prayer; it's slow, rhythmic, methodical and yet improvised. It carries a lullaby tone, but its sincerity jolts me awake; he thanks his heavenly father at length for allowing him time to exercise this morning. Elder Goynes becomes silent, and in unison they say, "We pray in the name of Jesus Christ, Amen," as they always do when they end a prayer.

After the prayer, the two sit in silence reading the Book of Mormon, the King James Bible and lessons from their teaching manual, Preach My Gospel. I sit in silence, studying their faces.

Elder Camper is a baby faced 19-year-old from St. Michaels, Md., a small and wealthy town near Chesapeake Bay. He puts product in his well-trimmed, brown hair and styles it ever so slightly in a fauxhawk. Elder Camper played baseball in high school and his muscular physique shows his athleticism. He sprays on Calvin Klein cologne, which somehow smells imprudent on a man with so many personal restrictions.

After graduating high school, Elder Camper went on a weeklong party with friends who binged on alcohol and drugs. He wanted something more meaningful for himself, so he signed-up for a mission, becoming the first missionary from his area in decades.

His Mom didn't pressure him into going, she told me later on the phone. She had thought he'd stay home and attend the police academy he'd enrolled in. She exchanges emails with him every Monday, the only day missionaries are allowed to send emails home. "It's been a lot easier than I thought. I miss him incredibly, but I have such a peace about what he's doing. He seems so happy and that makes me happy. It takes away the worry of having a teenager across the country." Still, she's afraid of California's earthquakes.

Elder Goynes is a rosy-cheeked 23-year-old from Baton Rouge, La. He puts a little product in his hair too, to tame his spiky crew cut. He hides his muscularity well, but it's there. He's the more extroverted of the two, and always seems to be talking without hogging the conversation. He tells me that he's strayed from the path in his life, but that's hard for me to believe that from a man who asks every person he meets, "How can I help you today?"

Before becoming a missionary, Elder Goynes drove Peterbilt trucks around the country, dropping them off to new buyers. Impressed by his hard work ethic, the company president asked him to be part owner. But God called him on this mission instead.

The silence lasts for an hour -- or almost an hour -- when Elder Camper asks his companion if he's ready. "We still have four minutes," replies Elder Goynes.

At exactly 9 a.m. Elders Camper and Goynes join two other missionary roommates in the hallway. They stand side by side, staring at the sheet music tacked to the wall. They briefly hum the rhythm of the song, then sing in surprising harmony: "Two thousand stripling warriors, young men of pow'r and might. Responded to the battle cry. O who will stand and fight? Behold, our God is with us!" The men sing slowly, in low voices that blend with a haunting persistence.

[][][][]

For young Mormon men, going on a mission is a right of passage, but not required. At 19, Romney spent 30 months in France as a missionary and converted 10 to 20 people to the LDS Church, by his own estimation. Convincing the wine-loving French to join a religion that prohibits alcohol might be almost as hard as winning 270 electoral votes. In 2007, approximately 30 percent of all 19-year-old LDS men became Mormon missionaries; from LDS families that are active in the church, approximately 80 to 90 percent of young men served, according to The Salt Lake Tribune. The missionary men always serve with a companion; they are never to be farther than shouting distance apart. The church has 55,000 missionaries worldwide today, including about 7,000 women, referred to as "sisters."

Hopeful missionaries must pass a test of worthiness. If you've had a child out of wedlock, a homosexual experience or committed a serious crime, you're not worthy, according to the LDS Church. The missionaries are typically 19 to 26 years old, but there are senior and married couple missionaries too. After completing a six week training program, they are assigned to a region typically far away from home, and spend two years dedicating their lives to bringing people to God.

The missionaries have to be frugal. They don't get paid -- in fact, they pay the church to go on a mission. Each missionary, often with the help of relatives, must pay $400 a month or almost $10,000 over two years. That money goes into a general church fund, which pays for each missionary's total living expenses and helps offset the costs for missionaries serving abroad. The church provides housing and a shared car, and gives each missionary $130 a month for food and most other living expenses.

Elders Camper and Goynes have been in Arcata for a month now. They love the natural beauty of the place, they say, but they love the people here even more. They're serving in the Santa Rosa Mission, which stretches along the coast from Vallejo to Crescent City, and is importuned by 180 missionaries, including 16 in Humboldt County. For two years these elders will move around the region, typically assigned to new companions and new service areas every three to six months. Mission President Rene Alba, an unpaid clergyman who will serve his position for three years, said shuffling the missionaries around prevents them from becoming too "chummy" with the community and losing focus.

[][][][]

After their hour of silent study and their brief, haunting song, the companions start their second, more talkative study session, that always begins by reading aloud five pages from their Missionary Handbook. Elder Goynes has five marks in his handbook, one for each time he's read through it. They read passages from the King James Bible and the Book of Mormon out loud to each other. Then they discuss their itinerary for the day, planning whom to visit and how to teach them. Each visit is custom tailored. "He's got a short attention span, so don't go on too long with the Joseph Smith lesson. Let's stick to authority," Elder Camper tells his companion.

We're running late when we leave the apartment at 10:46 a.m. Elder Goynes climbs into the driver seat of the church's silver Dodge Caravan. (The church also provides gas money.) A few boxes of the Book of Mormon and religious pamphlets sit in the trunk. Elder Camper stands behind the van and watches Elder Goynes back out. It's another rule; one companion always stands outside when the car is in reverse. If Elder Camper were backing out in a desert and the nearest obstacle was 20 miles away, Elder Camper would still get out and watch him. We say a prayer and drive off, listening to a CD of a church leader speaking on the importance of missionary work. "Such a good line," Elder Goynes exclaims every other minute, after a particular passage resonates with him.

We arrive at an apartment complex near Health Sport in Arcata. Before we get out, we say a prayer and grab a few extra copies of the Book of Mormon. A little optimistic, I think. Elder Goynes smiles and waves at every passing car. We stop and chat with a few passersby. Sometimes the conversations flow easily, but others carry awkward silences with a clear subtext: Please stop bothering me now. They ask every person they encounter the same question, "Is there anything we can do right now to help you, anything at all?" Yesterday a college student took them up on their offer, and the elders spent the afternoon helping her move furniture into her new house.

We walk around the back of the apartment complex when a car cruises by and the driver lifts a hand to wave back at Elder Goynes. "They're always so nice in their cars," he says.

The elders spot a young woman smoking a cigarette on her second-story balcony. It's a sort of Romeo and Juliet scene gone wrong. The Elders profess their love of God, but the young woman fails to return it.

"I'm spiritual, not religious," she tells them.

"We hear that a lot," say the missionaries.

"Why do you go to people? Why not let them come to you?" she asks in a stern voice. "Christ tells us to go everywhere," replies Elder Goynes.

The missionaries tell her they want to bring happiness into her life with the Book of Mormon. She says being miserable helps her art. Her roommate comes out and tells them very politely that he's an atheist, that the universe is an accident, just a bunch of chemicals in our brain, and we're all taking it way too seriously. The young woman chimes in, "Hey, I got a book for you to read!"

"Oh yeah, what's it called?"

"Cruddy, it's a graphic novel by Lynda Berry and it's about murder and drugs." she says tauntingly.

The elders write down the name of the author in their notebook and agree that the next time they're in the library they will try to check it out. The elders make a deal. They'll read her book if they can come up and give her the Book of Mormon. Even though the church normally regulates their reading, this departure is allowed to save a soul. She agrees. There's a feeling of truce when they meet at the door. (Because the church regulates their reading, they said later, they actually will not be allowed to read Cruddy until their mission ends.)

Back in the van, the elders pray for that woman on the balcony. Not that she finds the Book of Mormon to be true, although that would be nice, but that she finds happiness and that she may never be lonely. "How did we do?" they ask me. "You did about as good as you could," I answer honestly.

Days later I called the young woman, Bryn Robertson, and asked about her encounter with the Mormons. "I don't really like it when I've made it clear that I'm not interested and people persist. Then it feels intrusive," she said, adding that she does try to keep an open mind to all beliefs. "I felt like in the beginning it was sincere. It switched halfway through and felt superficial. Then they spoke their agenda." The Book of Mormon is still on her desk, unopened. She means to look at it eventually, just to stay open minded.

We forge on, door after door, among the hostile and the curious, before the elders lunch at their apartment. They insist on fixing me a chicken pot pie. "They're really good and they're like a dollar at the store," says Elder Camper, glad for such finds on a tight missionary budget. It's 1:45 p.m. and we have to be in Eureka in 15 minutes. Elder Camper stands behind the car and chaperones Elder Goynes as he backs out. We say a prayer and take the 101 south.

"Are there any parts of your faith that you don't agree with?" I ask the elders.

The car is silent in contemplation until Elder Goynes lets out a sigh and says, "I'd have to think about it for a while. Let me get back to you on that one." I was surprised. I figured everyone saw cracks in their religion. So I pressed it further. "What about gay marriage?"

"Elder Camper and I have both have friends back home that are gay. People think we hate gay people, but that's not true at all," says Elder Goynes. "The church is against it, but we accept all people and invite them to church." Elder Camper tells me that in his last transfer in San Rafael he helped baptize a woman who used to be a lesbian, until she found Mormonism. Days later, after thinking it over, the elders tell me they don't disagree with any part of Mormonism. They're not cafeteria Christians, picking and choosing what they do and don't like. They consume their faith whole.

At 2 p.m. we meet with 10 other missionaries to inundate a small area with elders and sisters -- they call it a blitz. The sisters hand each companion an index card with a list of names and addresses to visit. These are people who haven't been active in the church for a while or maybe showed an interest recently.

We get in the car, pray and drive to the first address on the list. Elder Goynes knocks on the door. "Friends knock, strangers ring," he says. No answer. We hear the TV blasting next door and Elder Goynes takes the opportunity to try the neighbor too.

A fat man with a scruffy beard opens the door. He takes one look at us and says, "I can't help you." SLAM!

The elders experience this every day. They got 10 antagonistic people in a row yesterday, but the day before that, they had a string of people receptive to their message. A couple weeks ago, two men answered the door naked.

"Doesn't that shit stuff piss make you mad?" I ask the elders. "How do you guys deal with that?"

Elder Goynes would later show me a Bible verse, Luke 6:23: "Blessed are you, when men shall hate you, and when they shall separate you from their company, and shall reproach you, and cast out your name as evil, for the Son of man's sake."

We approach a man gardening in front of his beautifully refurbished Victorian home. "How ya doing today sir? Is there anything we can help you with right now?" Elder Camper asks. The man tells us to leave without even a glance in our direction. "Not here fellas; you gotta move on. Move along now."

[][][]

From the beginning, Mormons faced distaste and ridicule from mainstream America. After the church was formed in the early 19th century, Smith moved his reformed Christianity and its followers from state to state, essentially being evicted by governments that detested the religion's belief in polygamy.

The church eventually settled in what was then Utah Territory, where it's still headquartered today. The LDS Church abolished plural marriage in 1890 after the federal government seized its assets. There is still a tiny Mormon Fundamentalist church that practices polygamy, but the LDS Church treats it like a crazy uncle, excommunicating its followers.

Over time, stressing hard work and an all-embracing safety net for fellow church members, the church became what it is today -- wealthy, established and largely Republican. Mormons have climbed political ranks, with 15 church members currently serving in Congress, including Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid. Although Reid is a Democrat, almost 80 percent of LDS Church members are Republican, according to Bob Rees, a Berkeley theology professor and practicing Mormon. When Rees teaches comparative religions, he reminds students that all faiths have practices or beliefs that seem odd to outsiders, but prejudice against Mormons is disproportionate, one of the remaining acceptable prejudices in American culture.

The church is also resolutely businesslike. In a 2011 cover story, Newsweek magazine compared the LDS church to "a sanctified multinational corporation -- the General Electric of American religion ... with an estimated net worth of $30 billion." Mormons are taught to give the church 10 percent of their income. Romney has implied that this tithing is part of why he should not release more tax returns. "Our church doesn't publish how much people have given," Romney told Parade magazine. "This is done entirely privately. ... It's a very personal thing between ourselves and our commitment to our God and to our church."

[][][]

After the Eureka blitz, we pray and drive to the Eureka church for a baptism. It's 40 years old, small and made of wood that blends in with the surrounding woodland beside St. Joseph Hospital. A couple dozen people meet in a classroom-sized room with fluorescent lighting and metal folding chairs. The woman getting baptized is in her mid-30s and wears a body-hugging dress, a dress so white it almost glows. Add a train to this floor-length gown and it would evoke a wedding. We pray and sing hymn number 157, "We Are Not Ashamed to Own Our Lord." The Eureka sister missionaries then sing a duet in perfect pitch, so perfect that tears glisten in the eyes of the people sitting next to me.

After a half hour or so of singing and praying, we all cram into a small room next door, with a blue-tiled basin called the baptismal font. A large mirror hangs above so friends and family can see from every angle. The woman plugs her nose and Elder Nathan Tubbs, a missionary dressed in a white robe, guides her head back and submerges her fully, then brings her back up. The room is silent. Only the water dripping off her body into the pool makes a noise. Two men quickly step in and close doors in front of the font, as if to say, "‘Nothing to see here, folks, move along." The whole thing lasts maybe a minute. I nearly bring my hands together to clap -- it feels like an applause moment, but everyone stands quiet. The group migrates back to the original room to sing hymn number 227, "There is Sunshine in My Soul Today." The newly minted Mormon comes in midway through the song, her hair still wet and up in a bun. Again I want to clap or whisper congratulations or offer a hug. But the service goes on.

We leave the church at 7:19 p.m. and hit the streets again to spread the word of Jesus Christ. I'm constantly yawning, while the elders seem to have eternal energy. More knocks yield nothing. More doors slam. We do this for another hour and a half before calling it a night. The elders typically return home at 9 p.m. They'll journal for an hour, prepare plans for the following day, pray, and then it's lights out at 10:30 p.m. Before leaving the van, Elder Goynes recites the mileage we covered today and Elder Camper records it in a notebook -- mileage limitations are another rule.

It's time for me to depart. We gather in a circle in their apartment, bow our heads and Elder Camper leads us in prayer. "O dear heavenly father, help Scottie to find the Book of Mormon to be true," he says. Hearing my name shocks me. But then he asks his savior to help me write an awesome story with a clear head. I appreciate the gesture and I sure as hell heck need all the help I can get.

I step outside into the cool, Arcata air and immediately untuck my shirt -- it feels vaguely sinful. I hop onto my bike and head straight to Redwood Curtain to meet a friend and a former professor for a much needed beer or three. The bar brings sunshine to my soul. I tell a joke or two with vulgar punch lines. I'm happy to stop censoring the occasional curse word. I swig my goblet of duppel and tell my drinking partners, "I met two really nice guys today." I am awed by their niceness, their rules, their implacable lives. Then I order another round.

Comments (47)

Showing 1-25 of 47

more from the author

-

Bar from Afar

Humboldt’s retired assistant district attorney working from Southern California

- Nov 29, 2012

-

Relaxed Reelection

With no opponents, incumbents kick back in Arcata

- Nov 8, 2012

-

Hempin' It

- Nov 8, 2012

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023