Taking on City Hall

Janelle Egger sued Fortuna to gain access to public records on its water system, and won. Or did she?

By Heidi Walters[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

At a public hearing next Monday, Jan. 18, the Fortuna City Council will consider a plan to demolish two aged 500,000 gallon water tanks on Stewart Street, and build a 2 million gallon reservoir on the same site. Like the old tanks, the new tank would provide water for the city's largest pressure zone, which serves most of downtown, and accommodate already zoned-for growth.

Approving this plan would, for many, seem a happy conclusion to a long, bitter debate. A couple years ago, the city had voted to put the new tank smack in the middle of the beloved Rohner Park forest. City staff had said it was the easiest, cheapest option. (See "Save the Trees," July 17, 2008). Fierce outcry, from across the city spectrum: This was the people's own woodsy playground! And, according to renowned redwood scientist Steve Sillett, it was a rare, prime example of mature second-growth redwood habitat. So the city shifted its focus to other sites, although, city officials say, it wasn't emotion that nixed the forest tank plan, but the threat of a costly two-year study to see if marbled murrelets used the forest, which likely would be inconclusive.

Nevertheless, approval of the Stewart Street project -- the city's new preferred alternative -- would cap the victory for the forest lovers.

Except, perhaps, for Janelle Egger. For her, the question long ago ceased to be about where to put the new tank. The question became, does Fortuna even need a new tank?

And that inquiry led her straight into a protracted public records battle with the City of Fortuna. At the peak of the engagement, last January, Egger sued the city under the California Public Records Act to compel it to provide documents she'd repeatedly requested. She prevailed, and in March got her documents -- including one the city had withheld citing Homeland Security concerns -- and last June Humboldt County Superior Court Judge John Feeney ordered the city to pay her attorney, Paul Boylan of Davis, $22,728 for his fees and court costs.

But it wasn't over. Egger says her dealings with the city post-lawsuit -- some friendly staffers notwithstanding -- got worse.

"It was an empty victory for me," Egger said, over coffee last week at the Hot Brew in Fortuna.

Now, 15 months since she made her initial public records request, she's edging closer to proving a new tank might not be necessary. But the question may be moot. Next week, the city's considering whether to put its new tank at Stewart Street, not whether there should be a new tank at all.

Janelle Egger had set out with one mission -- to get the city to make a better tank decision -- and got sidetracked into an all-consuming public records tango with Fortuna. Was it all worth it?

Janelle Egger is not a firebrand. The softspoken 54-year-old exudes "nice." But her short, salt-and-pepper hair and tailored, outdoorsy clothes reveal a down-to-earth no-nonsense sensibility. Quietly, she's always been involved somehow in chasing down justice. In high school she permanently ditched her senior physiology class -- except to take the tests, which she did well on -- because the teacher made sexist jokes and put Bible questions on the tests. In the 1970s, she worked for a program at Humboldt State that helped tenants understand their rights. She's long been active in the Democratic Party. In 2008 she helped Clif Clendenen get elected as supervisor.

Also back in 2008, Egger and her husband, Neil Palmer, put in a lot of time in the fight to keep the water tank out of the forest. She went to City Hall for agenda packets, researched the park's history, made fliers and helped collect petition signatures.

Some petition signers, she said, asked no questions. But others told her, "They don't need that tank."

Those people kept mentioning Vancil Reservoir, a 5 million gallon tank about a quarter mile up the road from the Stewart Street tanks. It held more water, they said, than the city needed. But it was in a different, higher-elevation pressure zone than the Stewart Street tanks.

She also kept hearing people grumble about their soaring water rates -- it reminded her of being a kid and going with her broke mom to negotiate in-person payments on the water and power bills. Since 2006 Fortuna had been hiking water and sewer rates to fund system improvements and pay back a related $20 million loan.

"And so this was all in the back of my mind," Egger said.

Once the forest was saved from tank duty, Egger dug into the new question: Why couldn't the city use Vancil Reservoir? If it was feasible, Egger figured using Vancil might be a heckuva lot cheaper than spending the projected $4 million to build a new tank.

As far as she could tell, City Council members hadn't even asked that question.

She researched, and learned that the city required about 4.5 million gallons in storage, and that it already had 6.75 million gallons available at Vancil and elsewhere (not counting two failing reservoirs). If Vancil replaced some of the Stewart storage, there'd still be over 2 million gallons for reserve.

She kept hearing that Vancil was built for emergency storage in 1965 in direct response to the 1964 Eel River flood, which had inundated low-lying city wells and the treatment facility and sullied the drinking water. City Council members said so. Recent news stories had said so. But she found historical newspaper reports that contradicted the commonly held belief, and they indicated that, in fact, the reservoir had been planned before the flood to replace the Stewart Street tanks as the city's main supply, and to accomodate anticipated annexations.

She presented her findings at council meetings and she posted them on her blog Fortuna Citizen. Other people asked about Vancil, too, and at one meeting a city consultant said yes, it would be a feasible alternative. Egger wondered if the city was doing a cost analysis of using Vancil.

She started asking for public records.

Things started out nicely enough. At 9:47 a.m. on Sept. 24, 2008, Egger sent an e-mail to Fortuna City Engineer Dennis Ryan (who is named in her lawsuit):

"Hello, could you please send me a copy of the City's Water Pressure Zones map that was presented at the August 12th study session. I would also appreciate a full size copy of the Water System Schematic that was in the upper right corner of that slide.

"Mr. Rigge indicated at the last City Council meeting that there has been some investigation of using the existing Vancil St. reservoir for zone 1. If there are any consultant or staff reports regarding this I am requesting copies of those as well.

"For any of the above that can not be emailed please let me know as each is available for pick up at City Hall.

"Janelle Egger"

At 10:04 a.m., Ryan e-mailed a reply:

"Hello Janelle,

"I will try to gather this information today, as it is my last day of work for the City this week (I am currently working Monday-Wednesday). If I am not able to get this together today, I will try to delegate it, OR -- it will be a high priority early next week.

"We are working on a limited analysis of the cost to use Vancil to serve PZ1. This analysis will be included in the Staff Report for the next Council Meeting (not yet scheduled).

"Call or email if questions.

"dennis"

On Sept. 29, Kevin Carter, an engineering technician with the city, e-mailed Egger to let her know he had printed out a color zone map for her, and he had included the city's piping on it. However, he wrote, "I can not include the schematic that was in the upper right corner [due] to confidentiality. I am sorry that this could not be on the map."

There'd be a $6 charge to cover printing costs, and she could pick up the map at City Hall.

Egger, at Hot Brew last week, admits that after she got the map she sent an unnecessarily snippy note back to Carter -- partly because she'd misinterpreted his comment about the pipes. In that e-mail and one to Ryan, she once again demanded a copy of the schematic.

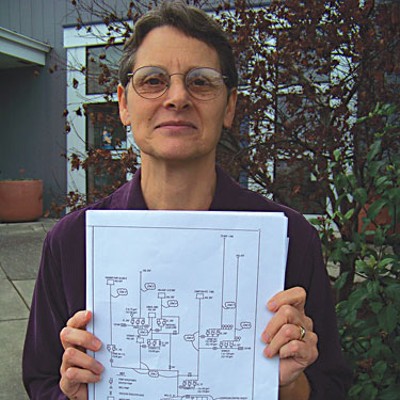

Egger wanted the schematic -- a diagram of the city's wells, tanks, pumps, valves, water treatment facility (and nearby chlorine tank) and associated elevations -- to better understand the system and to use as a tool to illustrate her findings to the public and the council. She'd seen a smaller version of it in a PowerPoint presentation at a city meeting, and she actually had a paper copy of it she got from a city consultant, but that was outdated and had notations scribbled on it.

She apologized to Carter a week later, and asked again for the schematic. And if he couldn't provide it, she demanded "an explanation of how a publicly displayed document is exempt from public access."

Ryan's Oct. 9 e-mail to Egger explained why the city wouldn't give her the schematic:

"Subsequent to 9/11," he wrote, "the Department of Homeland Defense notified public agencies and directed that information regarding certain elements of public infrastructure systems be held in confidence, due to the information possibly or potentially being used in the planning of a terrorist attack. Ironically, some information that had previously been REQUIRED to be shared with the public through public meetings and workshops, proved to be some of the most sensitive information. This was all a part of the collision of our previously and passionately held belief that we were secure in our homeland with the current world reality of international terrorism -- and unfortunately our previous perspective did not survive that collision."

Ryan added that when he was preparing the original map for the presentation Egger saw, it hadn't occurred to him the schematic was one of those sensitive documents. City Manager Duane Rigge (also named in the lawsuit) later asked that the schematic not be circulated to the general public.

So Egger focused on getting information on the Vancil cost analysis. In numerous e-mails, personal meetings and phone calls, she got the same answer: "Wait for the staff report."

She told city staff that, under the California Public Records Act, she was privy to the facts that city staff and consultants were gathering on Vancil. On Oct. 21, Rigge wrote Egger a long letter again denying her request. "The information you are requesting consists of preliminary drafts and notes made in the process of preparing a final document and therefore are not subject to disclosure," he wrote. He backed it up with excerpts from case law.

This was right before the November election, and Egger set aside her quest to work on Clendenen's campaign. But then, she said, Rigge announced that the special meeting on the water tank project would be Jan. 12, and the long-awaited staff report would be released the week before.

"In my mind, that's no time," said Egger. "So I read his letter again, and I looked at the case law he quoted, and I went and read that case: Coldwell v. Board of Public Works. It was decided in 1921, before the Public Records Act. And it does say what they said. But there's more to the story."

She said the case law actually concludes that it is important to allow people to see preliminary records. She wrote a letter back to Rigge, quoting the pertinent sections.

Eventually City Attorney Dave Tranberg got her letter. She waited for a reply, then demanded one by Dec. 4. On Dec. 18 she got one, the nut of which said: "We do not know of any reports or items held or retained by the City as requested."

"And when I saw that letter, it was like, 'Oh shit,'" said Egger. "It dropped the issue of preliminary records and they just said they didn't have the reports I asked for."

Meanwhile she'd found an attorney -- Paul Boylan -- through a Web site called Californians Aware: The Center for Public Forum Rights. He took her case pro bono, and on Jan. 16, 2009, he filed a petition for writ of mandate under the CPRA.

"It was not a lawsuit for damages," Boylan said by phone last week. "It was a lawsuit seeking an order to compel records to be turned over."

Boylan said he entered negotiations with the city's attorney, Dave Tranberg. "He was courteous and professional. The discussion was rapid." In March Egger got the records: the schematic, and 62 pages of documents including some handwritten notes related to the Vancil analysis.

City Manager Rigge denies, however, that the lawsuit compelled those documents. In his declaration protesting Egger's petition for attorney's fees, he said that those particular documents were in reponse to a new request she made, post-lawsuit. The only document she got after the lawsuit that was one she had earlier requested, he said, was the water system schematic.

And even that, he said later by phone, the city had finally decided to give to her.

Nevertheless, Judge Feeney determined that Egger had prevailed, and ordered the city to pay Boylan's fees and costs -- not at the $450 an hour fee that Boylan had hoped to get, but at $320 an hour.

The Vancil documents offered mere tidbits. But mostly they just prompted more questions. And the staff report, presented at the public hearing, had only discussed Vancil in the appendices. Conclusion: Yes, it was feasible to use Vancil for regular storage, with some revamping of the system because Vancil is in a higher pressure zone than the Stewart tanks. It would cost money, but not nearly as much as the new tank construction. That said, the report implied that Vancil was better kept as emergency storage. And it said it would be unwise to eliminate all storage in zone one, where the Stewart site is, because that would mess with the city's setup for fire flows, perhaps riskily.

Egger found the discussion incomplete. So she asked for the city's Excel workbooks and supporting workbooks so she could make her own financial projections for a scenario the city hadn't considered -- demolish the leaky reservoir at Stewart, but use Vancil in concert with the other, non-leaking one. Then she was told that reservoir leaked too. She asked for the records showing it.

They sent her financial files, but they were locked. When they were unlocked, they weren't all there. And she was told there were no records on the round reservoir's leaking.

"When I questioned this [I was told] I was making a new request, please put it in writing and identify the type of document and the time period when the record was produced," Egger said in an e-mail to the Journal last week. "I was baffled. It didn't get any better."

In October, she complained to City Council. And another attorney that she'd found through CalAware -- Karl Olson -- sent a letter to the city reminding it of its duty to help citizens make their requests. After that she was deluged with boxes.

"The response to the letter was to fill a room with records," Egger said. "Many if not most of them were of no apparent use to me."

City Council member Doug Strehl, by phone last week, expained what happened. "She asked for all the information that had to do with the water tank," he said. "And when our city lawyer heard the word 'all,' he told staff to bring all the records that have to do with the water tank. One of the water tanks is a hundred years old and the other is 75 years old."

Eventually Egger and an employee emptied the box room, from which she had culled about 200 useful pages. Egger wrote a letter to Rigge.

"I had hoped," she wrote, "that our efforts would be the beginning of a more logical and time-saving approach to identifying records. However, the boxes continued to come." She noted how she'd had much speedier, fruitful results when she'd sought records from the city's finance director, and from California Department of Public Health's Drinking Water Division whose policy says, "If you are not sure what records you want, or how to describe them, we will help you."

Egger, last week at the Hot Brew, said she just kept hitting a brick wall with the city and its public works department.

"The upshot was, I was 'the enemy,'" she said. "And we couldn't communicate with each other."

On her other blog, Fortuna Exchange, Egger has chronicled her public records saga. Some readers have offered praise. Others, flack: Why did she cost the city, and taxpayers, all that money?

She answered: "I have no interest in the right to uninformed speech. If you and I do not have information on which to form an opinion, then when we speak we are confined to expressions of our uninformed emotions."

It was the city, she said, that cost the people money and wasted its staffers time.

In his declaration in opposition to Egger's motion for attorney's fees, City Manager Rigge said that at one point "it became clear ... that Petitioner did not desire existing records, she wanted access to the city's thought process as it wrote a staff report, so that she might perhaps affect its conclusion."

By phone last week, Rigge curtly said the city did not block her access. "She asked for a public record, and we provided it," he said. "It was a question of the timing of providing that document." He said the city had finally decided to give Egger the initially requested documents, but then she sued.

"She did not need to do that -- a lawsuit. Didn't need to do it. She just cost every rate payer -- and I publicly announced this after the settlement-- she just cost every water ratepayer in the City of Fortuna $5." Plus, he said, to fulfill her many other requests after the lawsuit the city had to pull staff away from other projects and hire temporary helpers.

"We haven't summed up the total cost yet because she's still going," he said. "Which is fine. It's her right."

Councilman Strehl said he admires Egger. "It isn't every day you go up against your local government and tell them they're doing something wrong," he said.

It can sway the decision-makers. Strehl was all for the tank in the forest until people urged him to go walk through it and notice its beauty and all the people using it. It changed his mind.

She hasn't convinced him on the Vancil option, however. He wants the new tank. "I don't want to go backward in storage," Strehl said.

Has the Egger affair changed the city's approach to public record requests? No, said Rigge, because there's "never been a problem in the past, and I hope we never have a problem in the future. It happened to be with this particular individual asking for records."

Paul Boylan, Egger's hotshot first attorney -- who says that in his 20 years of public records law he has only lost one case -- says his public record work almost always takes place in small towns.

"Governments have a tendency to say 'no' before they say 'yes,'" he said. "In places like San Francisco and Los Angeles and San Diego, they have policies that take away from government employees the discretion to say 'no.' So there is rarely ever such litigation in a place like San Francisco or Los Angeles. They've learned the hard way."

Most small towns just don't get as much practice answering public records requests. But Fortuna's certainly been feeling exercised these days.

Comments (17)

Showing 1-17 of 17

more from the author

-

From the Journal Archives: When the Waters Rose in 1964

- Dec 26, 2019

-

Bigfoot Gets Real

- Feb 20, 2015

-

Danger at McCann

A kayaker's death has raised safety questions about low-water bridges

- Feb 19, 2015

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023