[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

The village of Westport is the last outpost before Mendocino County's northern coast disappears into a roadless swath of rugged shoreline and redwood-carpeted hills. It is spread across roughly one mile by one-half mile of coast, and has one store, two gas pumps and 47 registered voters. Retirees are Westport's dominant demographic, and 15 miles of coiling coastal highway separate it from the closest town.

In this very small village, there is one political entity -- the five-member Westport County Water District, which oversees the local volunteer fire department and provides sewage treatment and water to several dozen homes. In this very small district, there have been many fiery debates over the years between board members: Sheriff's deputies were called to intervene at a meeting. Recalls have been organized. And in one now infamous case in 2005, Alan Simon, the board chairman at the time, was nearly killed in the doorway of his home by nine shots from a semi-automatic .22 Ruger pistol.

Shortly after the shooting, Kenneth "Kenny" Rogers, Simon's water board rival, was arrested for soliciting Simon's murder. At the time, Rogers was chairman of the Mendocino County Republican Central Committee; he had also recently been fired from his post as Westport's assistant fire chief and replaced in a recall by Simon as the water board's chairman.

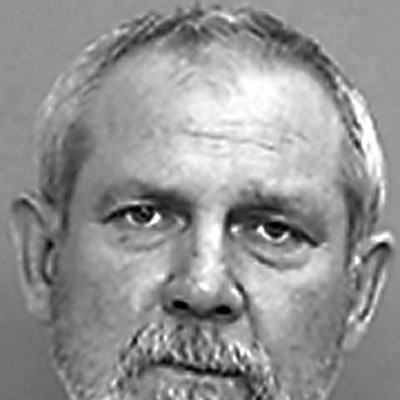

The district attorney's case against Rogers meandered through the courts for years, with continuances and a near no-prison plea deal. But on July 22, after a two-and-a-half week trial at the Ukiah Superior Court, Rogers, a lanky 51 year old who never failed to greet jurors without a beaming smile, was convicted of conspiracy and attempted murder. He faces 25 years to life in prison -- though it appears he's gearing up for an appeal, and the possible claim of a mistrial: Shortly after the verdict, attorneys learned that one of the jurors had lived with a reporter who'd covered the beginnings of the Kenny Rogers debacle. A hearing is scheduled for September 11.

The possibility that the juror was "tainted" doesn't seem likely: She told an investigator that she and the reporter, Frank Hartzell, no longer live together, and that she hadn't talked to Hartzell about the case since 2005. But nothing in this story seems likely.

As told by Tim Stoen, the deputy district attorney who prosecuted the case, the story of Kenny Rogers was as salacious as they come, a story without parallel outside the Emerald Triangle. It was a story of a vengeful, pot-growing Republican official who hired a hit man to murder a political enemy -- and offered to pay for the job with marijuana. It was a story of an ambitious politician with a lethal style of small-town politics. By day, Stoen argued, Rogers was one of the North Coast's few proud conservatives, but by night he was a man who hung around hardcore felons -- and hired them to do his dirty work.

It was about 10:30 pm on the evening of June 17, 2005, when Alan Simon heard something at the front door of his gray, two-story home on Hillcrest Terrace, one of Westport's few residential streets.

"I was getting ready for bed and brushing my teeth when someone loudly and aggressively started banging on the door, saying 'Kathy -- where's Kathy?'" Simon, 53, recently testified. "The hairs on the back of my neck went up. I knew something was wrong."

Simon said he told the man that no Kathy lived there. Then he called the police. The man, Simon told the dispatcher, was a white guy with a fu-manchu-style mustache. "I opened the door and he wasn't there, so I stepped on the threshold and saw a man leaning up against a white sports car with his arms crossed. I held up the phone and said 'The police are on the way.' He walked toward the yard and said, 'Hey man, I don't want any trouble," Simon said. "Then his right arm came up. He had a gun and he fired it. I ran in, shut the door and hit the deck... My front door was exploding around me."

Police would later find eight shell casings from a .22 around Simon's house and nine bullet perforations in his front door. Simon had been grazed in the head and wrist; he was subsequently taken to the hospital. Police searched for the white convertible that night but found nothing. Stoen would later argue the shooter had hid out that night in Rogers' 320-acre property outside Westport.

The following day, a CHP officer who was on duty around Laytonville -- about 25 miles east of Westport -- spotted the white car driving east on Branscomb Road. The officer, Mark McNelly, flicked on his lights and pulled a U-turn; a minor chase followed. While in pursuit, McNelly said he saw the driver -- a man from suburban Sacramento named Richard Dean Peacock -- throw a white plastic bag out of the passenger side window.

Inside the bag, police would later learn, was the .22 Ruger used to shoot up Simon's house. Police would learn that Peacock, who would be convicted in 2006 of attempting to kill Simon and sentenced to 71 years in prison, knew Rogers.

Shortly after Peacock's arrest, cops started asking Rogers questions. So Rogers -- in a preemptive effort to clear the air -- visited his buddy, then-sheriff Tony Craver, in Ukiah, who referred him to a detective.

In a videotaped interview from three days after the shooting, Rogers was the charismatic gladhander Stoen would later describe him as -- even while detailing his loathing for Alan Simon. Rogers called Simon a "Hollywood guy," part of the "new blood" in town who didn't respect him. He called Simon an asshole. Rogers said he was an old body builder and that he'd love to punch Simon out.

Their beef, he said, could be traced back to the deep cultural divide that permeated his small coastal village: The fact of George W. Bush's 2004 re-election and his own unflinching embrace of Republican politics -- he told detective Andy Alvarado it was his "religion" -- had made Rogers anathema to local liberals. He told the detective that he and Simon had had "harsh words" on the local water board, and that he'd recently called Simon up and told him that if he didn't get water to the district's storage tanks, he'd "hang him -- politically." Simon would later testify that Rogers never used the "p" word to end the sentence, so at the time, he took the call as a death threat and called the sheriff's office.

Now, a few words on the Westport water board.

Kenny Rogers was appointed to the board soon after he moved his family from Sacramento to Westport in the late 1990s; he was appointed chairman not long after. Other board members would soon accuse Rogers of running a good ol' boy club where he'd give favorable water rates to friends and where district money seemed to disappear (a grand jury investigation from 1999 found a number of problems with the district, but didn't mention the above criticisms). At a 2004 meeting, Rogers and Keith Grier, the only black man in Westport at the time, got in an argument at a board meeting; Rogers accused Grier that night of injuring Rogers' wife. Deputies were summoned and Grier was arrested -- though Grier would later tell the DA's office he'd been "falsely accused" by Rogers. (Stoen said nothing ever became of the charges.)

Nevertheless, the seeds of the 2005 recall had been planted.

An anti-Kenny Rogers coalition formed and decided to nominate Grier as the new water board director. He declined, so Simon, then a recently retired film scout and relative newcomer to Westport, offered himself as the candidate.

Simon would later testify that once the recall papers had been filed by Velma Bowen, who'd also been a board member, Rogers began making house calls. He pleaded with the signatories to contact the county registrar and have their names removed. When Rogers visited Simon, and Simon refused, saying the recall was part of the democratic process, Rogers got furious.

In a strange courtroom exchange, Rogers' lawyer, David Markham, asked Simon what happened next. "You want me to tell you what happened next?" Simon asked, visibly uncomfortable with the question. "Yes, that's what I asked," Markham replied. After several moments of silence, Simon responded. "[Rogers] said, 'You want to have a nigger run this town? You want to have a woman -- Velma Bowen -- who's sucked the cock of every man in this town'" run the water board? Simon said he then told Rogers to leave.

As Simon spoke, Rogers, sitting at the defense table, shook his head; but at the time, his attorney didn't challenge Simon's testimony. It wasn't until the next day that Markham chalked up the exchange to an error on his part -- he said he shouldn't have asked the question -- and asked Judge Ron Brown to strike the testimony, which the judge agreed to do on the grounds that it wasn't relevant to the case. (Outside the courtroom, Markham declined to discuss the details of the exchange, except to say that Rogers never made the remarks about Bowen or Grier.)

On August 31, following Rogers' alleged unsuccessful drive to quash the recall, 50 of Westport's 68 registered voters at the time cast ballots. Twenty-nine voted to recall Rogers; 19 voted against. Twenty-eight voters elected Alan Simon.

Rogers had lost, but in a letter to the county registrar, he denied all allegations of misconduct: He said he'd spent countless volunteer hours working for the district; he said he'd obtained grants for district improvements, overseen equipment maintenance and only spent board-approved funds.

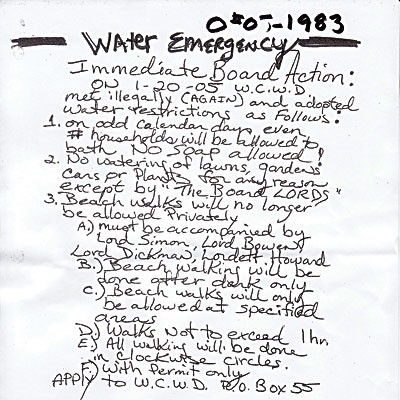

The following January, charging gross neglect, the board axed Rogers from his assistant fire chief post. Rogers told the board the move was illegal -- and that he'd see them in court. Soon after, someone smeared feces on the door handle of the Westport firehouse and on the front doors of the hotel Grier owned at the time. A note was posted outside the Westport store that referred to Simon as "Lord" and fearfully predicted a fascist takeover of the water district. It ended with a slur of particular insult to Simon, who is Jewish: Heil, Simon, the note said (though the note's writer misspelled "hile").

None of these incidents would ever be connected to Rogers. But the bitter, small-town politics of Westport's water district were about to get a good deal more bitter.

Six months later, in the sheriff's interview room, Rogers complained to detective Alvarado about his illegal firing. He told the detective that even though he couldn't stand Simon, he was dealing with the water board fallout with a lawsuit that demanded he be reinstated. This eventually happened, though Rogers retired as soon as he got his job back.

Rogers explained to Alvarado how he'd met Peacock -- along with Peacock's little brother, Michael -- years earlier in Sacramento through his auto shop. He described both brothers as convicts with long criminal records who he feared, but who he nevertheless helped out. He'd gotten Richard a landscaping job in Sacramento, he said, and he'd hired Michael because he need a "thug" to keep "Mexicans" from illegally growing pot on a remote part of his large property.

That "three carloads" of cops had embarked on Rogers' property after the shooting seemed front and center in the Republican chairman's mind, however. Rogers was, after all, on an upward trajectory within the party and angling for Sacramento. The last thing he wanted was bunch of sheriff's deputies lumbering around his property, especially when he'd failed to tell his Republican pals he was growing pot there. So when he visited detective Alvarado that June day, Rogers made sure to tell him he had 54 plants that belonged to his wife and partner -- along with the requisite medical cards. Cops would later discover he had nearly three times that many mature pot plants along with clones and garbage cans filled with shake.

"I'm just a bit paranoid because I don't want it to get out media-wise -- it could jeopardize my position within the party," he said, not knowing then that within days he'd be arrested for attempted murder, conspiracy, solicitation and cultivation of marijuana; that within months he'd resign his chairmanship; and that he'd soon leave Mendocino County altogether for neighboring Lake County.

Toward the end of the interview, in a statement Stoen would offer as evidence of Rogers' guilt, Rogers offered his own hypothesis of the shooting. "I think Al [Simon] would set shit up like this," he said. "I wouldn't put it past him."

The district attorney's office, of course, has offered a very different storyline since the case was first brought to trial in 2006: the DA has claimed all along that Rogers hired Peacock to off a political foe.

Following Richard Peacock's arrest, Peacock's brother, Michael, would contact police and tell them that just before the shooting, Richard had told him about his plan to go to Simon's house. He would tell police that Rogers had offered Richard payment of three to four pounds of marijuana to hurt Simon. Michael Peacock would tell police that Rogers had tried to hire him to beat up Keith Grier after the alleged assault incident -- and that Peacock had told Rogers he'd ask a skinhead acquaintance if he was interested (nothing ever became of the request).

Police would discover that the Richard Peacock had visited Westport shortly before the shooting, and that pistol he tossed out of his Miata had been reported missing by Velma Bowen, the water board member with whom Kenny Rogers and his family had stayed during the summer of 1999. Rogers, Bowen would tell police, was the only one who'd known where she kept the gun -- though Rogers had denied taking it when she confronted him.

On Rogers' digital camera, police would find a photo of the façade of Alan Simon's house. They'd listen to Rogers' and Peacock's jailhouse phone calls and cull together incriminating statements. But one of the prosecution's strangest -- and perhaps strongest -- pieces of evidence wouldn't turn up until later.

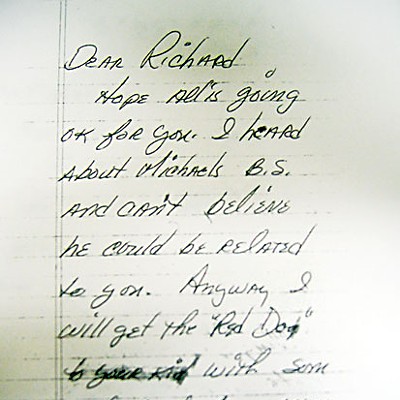

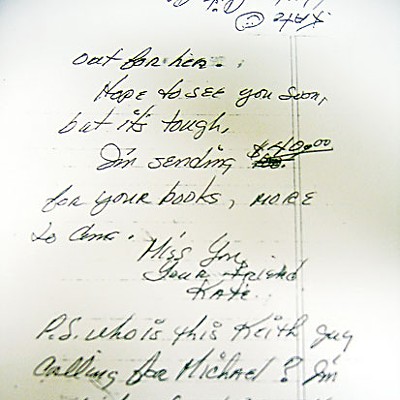

It was August 4, 2005, and Richard Peacock was at a preliminary hearing for the attempted murder of Alan Simon. A few days before, he'd received a letter in the Mendocino County Jail. It was handwritten, postmarked Yuba City and signed by a woman named Kate.

On the face of it, the letter seemed harmless. The author claimed to be sending Peacock's daughter school clothes and a red dog. At first, Peacock -- who didn't know anyone named Kate in Yuba City -- had no idea what to make of it. But that changed once the hearing began.

Rogers was leaving the witness box -- where he'd invoked his right to remain silent -- when Rogers looked at Peacock, flashed a smirk and winked. (Peacock would later tell sheriff's Lt. J.D. Bushnell he also saw Rogers pat his side, as if he had a gun.) Shortly after, Rogers' then-attorney, Donald Masuda, delivered a message to Peacock's public defender, Wes Hamilton. Rogers' wife was going to "take care" of Peacock's 13-year-old daughter, Bobbi, said Masuda, who would eventually excuse himself from the case for serving as the unwitting courier of a potential threat.

Hamilton passed along the message, and Peacock put these seemingly innocuous events together -- receiving the letter, the smirk, the gun pat and the message from Masuda. Then he freaked out.

In open court, even as his lawyer was telling him to zip it, he announced the message was a threat against his daughter. The "red dog" mentioned in the letter referred to the pistol grip of a .45 caliber owned by Rogers -- a pistol grip colored red and adorned with the image of a dog that Rogers had shown Peacock. He told Bushnell during a recess that Rogers made the threat because "he could be the one to put [Rogers] away."

When Peacock, 59, was called to testify in the most recent trial, he kept his mouth shut -- at least while the jury was around. Otherwise, he was forthright and gregarious; during a recess, he even lectured Stoen on the peckerwood prison gang. He also appeared to have aged a decade in the last four years, and was rolled into court in a wheel chair -- the product, he said, of a spinal injury suffered during a knife fight in Pelican Bay.

When the judge ordered Peacock to talk, he refused. So Brown, in a somewhat feeble reproach, found him in contempt. Then he sent him on his to way finishing what is essentially a life sentence.

The courtroom was packed as the attorneys prepared their closing arguments. On one side, more than a dozen people from Westport had made the slog down the coast and over the hill. On the other side was Rogers' family. Outside, someone was handing out a flyer -- called Snoopy's Spotlight Street Sheet -- which contained, along with verse about pedophiles and the CIA's once secret MK Ultra program, convoluted references to the case, including a mention of Tim Stoen's previous life at the People's Temple.

Stoen, who has an understated style -- and a habit of closing his eyes and bowing his head slightly whenever jurors enter the room, making him look a bit monkish -- appeared to have guzzled a few Red Bulls during a break in his three hour-plus closing statement; in its highly caffeinated final hour, Stoen referred to his witnesses with alternating superlatives: they were "first-rate," "class acts," "terrific," "upright" -- or, in the case of Wes Hamilton, "good and folksy." And, of course, he lobbed a few hyperbole bombs at Rogers, who was "grandiose, brazen," and a "legend in his own mind."

Markham didn't bother trying to top Stoen's presentation. He plodded through a PowerPoint presentation, offered an unmemorable quote from Buddha and recapped the weaknesses in Stoen's entirely circumstantial case. He stressed that the red dog was really a giant stuffed Clifford toy that had been won by Kenny Rogers at Marine World and promised to Richard Peacock's daughter; it was now plopped in the corner next to the judge's clerk. Not a word from the Brothers Peacock could be trusted, he said. And the gun that Rogers allegedly stole from Velma Bowen? It had, in fact, been in the Rogers' home all along, buried in a tool box -- never mind that Rogers had denied taking it in the first place. The photo of the house found in Rogers' camera was for a friend from Sacramento, a man named Eric Beren, who was house shopping at the time and who testified that Rogers occasionally sent him photos from Westport (Simon's house was up for sale at the time the photo was taken).

Peacock, Markham argued, had been a loyal, loose cannon of a friend, a man whose values had been crystallized not by the principles that informed reasonable, respectable Kenny Rogers, but by the many, many years he'd spent in prison. And when Peacock heard his pal was ticked off at Simon -- well, he did what any man who'd spent his whole life in prison would do.

"He wanted to surprise a friend," Markham said. "But Ken Rogers had no idea what he'd planned."

The verdict, which came after nearly two days of deliberation, was met with sobs from the Rogers family and hugs from Westporters. As soon as the first guilty charge was announced, Rogers' head dropped to the defense table. A few moments later, looking regretfully at the jury, he shook his head and mouthed the words, "I didn't do it." Then the bailiff escorted him out.

Outside the courtroom, with tears streaming down his face, Rogers' son Norman repeatedly told detective Kevin Cline he was a "sick motherfucker." For Simon, that post-trial exchange with Cline was just as frank -- but profoundly different.

"I shook hands with Kevin Cline and he said just one word to me," Simon said. "Justice."

Comments (100)

Showing 1-25 of 100

more from the author

-

Coward of the County

Former Mendo County Republican chief Kenny Rogers given 25 years for attempted murder

- Apr 8, 2010

-

Mendo Muddle

The North Coast's southern section is far from accord on the Marine Life Protection Act

- Jan 28, 2010

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023