[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

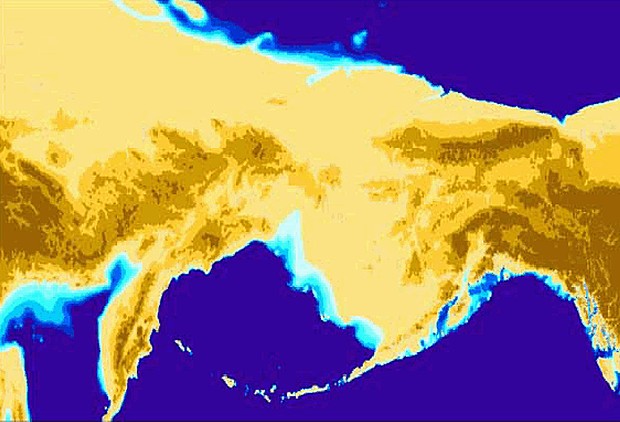

In the early 1970s, the question of when humans first came to the Americas had been decisively answered: 13,500 years ago. At a time when sea levels were 200 feet lower than now, big-game hunters migrated east from Asia across a continent-size land bridge ("Beringia") connecting Siberia and Alaska, then south through an ice-free tundra corridor along the course of the Mackenzie River to Alberta and beyond. This, in a nutshell, is the "Clovis-First" model, named for an archeological site near Clovis, New Mexico, which, in 1929, yielded hundreds of distinctive "Clovis" arrowheads and other stone tools made, presumably, by some of the earliest newcomers to the New World.

The first major crack in the Clovis model came in the mid-1970s, when archeologist Tom Dillehay dated campfires at a creekbank site, "Monte Verde," in southern Chile, to at least 1,000 years earlier than the Clovis arrivals. (Carbon-14 dating pinpoints when organic material, such as wood, last metabolized, in this case when it was used as fuel.) Since discovery of Monte Verde, another dozen or so sites in North and South America have challenged the conventional wisdom of Clovis-First, but none yielded definitive proof that it was wrong.

The picture changed in 2008 when DNA from human coprolites -- fossilized feces -- found in the Paisley Caves, 100 miles northeast of Klamath Falls, Oregon, was shown to be up to 14,300 years old. Two years later, a team led by Texas A&M archeologist Michael Waters struck gold on the banks of Buttermilk Creek in Texas with the discovery of some 20,000 stone tools from about 15,500 years ago. (They couldn't date the tools themselves, but a new technique lets them estimate the date when the surrounding soil last saw sunlight.)

With the Clovis-First model pretty well discredited, the next question is: How did those first Americans get here? While most archeologists tend toward thetheory of land passage across Beringia and down a wide ice-free corridor (following the opening-up of a contiguous ice sheet across present-day Canada), some support the idea of a sea route, with adventurous souls paddling along the southern coast of Beringia and down the western shore of the Americas. It was certainly technically feasible -- humans first crossed the Timor Sea to Australia 45,000 years ago -- and they could have sustained themselves on shellfish and salmon once ice cleared from the coast of British Columbia around 16,000 years ago.

One intriguing piece of evidence demonstrating the seafaring ability of Paleo-Indian sailors comes from Santa Rosa, one of California's Channel Islands. Recent discoveries at site "CA-SRI-512" show that humans were using stone tools there, similar to ones found in East Asia, to hunt geese, cormorants and marine mammals at least 12,000 years ago. But did they paddle all the way down the west coast to Chile? That's probably a question that can only be answered by marine archeologists, since any intermediate shoreline habitation sites are now under a couple of hundred feet of water. Whichever way they came, those early trailblazers were tough as nails, with a supreme ability to adapt to changing conditions before fanning out across the vastness of the Americas.

Barry Evans ([email protected]) considers paddling around Trinidad Bay adventure enough.

Comments (2)

Showing 1-2 of 2

more from the author

-

A Brief History of Dildos

- Apr 11, 2024

-

Eclipse!

- Mar 28, 2024

-

The Little Drone that Could

- Mar 14, 2024

- More »

Latest in Field Notes

Readers also liked…

-

Trouble on the Line: The Reality Part 2

- Nov 3, 2022