[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Goodbye, sugarpie

About five or six years ago — he can't quite remember when — Dr. Leo Leer and his colleagues at Eureka Family Practice turned a cold shoulder to the hordes of pharmaceutical company salespeople — drug reps — who hitherto had had free rein in their office.

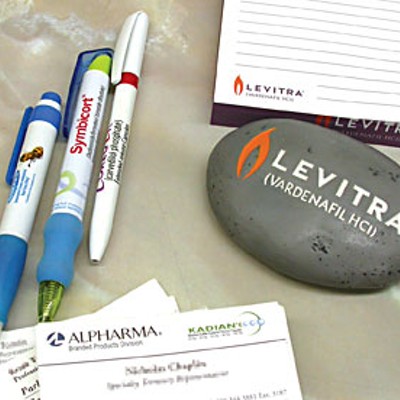

No longer could a well-heeled, uberfriendly, hypersmart, slick, sleek and quite often neighborly-faced instrument of Big Pharma come waltzing in like she (or he) owned the place and sail on down the hall until she bumped into a doctor. Nor could she ply the front desk with cookies, croissants and cappuccinos. Or scatter about handfuls of office supplies embossed with drug names and her company's label. Or try to set up a "drug lunch" to talk about her company's newest statin wonder drug, or a new procedure, or whatever. Or drop off an invitation to a fancy dinner to hear a well-known figure in the profession talk about her company's latest new hope, say, for the depressed and anxious — well, the drug rep could mail the invite, but Leer, for his part, would toss it in the trash.

The family practice made one concession, although Leer fought vociferously against it: The reps could still bring in free drug samples.

"Before, the number of reps we used to see was in the teens, for sure, and each one would try to reach us once a month, at least," said Leer on a recent weekday evening in his office on Harris Street after most of the staff had gone home. "They still come by. But we refuse to meet with them or see them or talk with them. And we decline any freebies [except the samples]. It annoys the heck out of them. They say, 'Well, we can't leave you samples,' and we say, 'OK.'" But those who still dare to come by end up leaving samples anyway.

Hold on — saying no to free goodies? Are these people crazy? Or some sort of pious upstarts trying to make everyone else look bad? Especially the food, which after all comes from local cafes and restaurants — what harm can a little edible do, in the big scheme of things?

Eye on Big Pharma

It's not a new story. For decades people have pondered Big Pharma's marketing ethics. Public Citizen — the group Ralph Nader started (but no longer is associated with) — has been harping on the industry for years now, digging up dirt on it and presenting such tools as the "Worst Pills, Best Pills: A Consumer's Guide to Avoiding Drug-Induced Death or Illness" which reveals the less savory things that companies don't advertise about some of their drugs. Former drugs reps have come clean and revealed the secrets of their profession. Journalists and doctors have written books and articles on the influence of gifting — the most touted among them pathologist Dr. Marcia Angell, former editor of The New England Journal of Medicine.

In response, the American Medical Association has recommended that doctors not accept gifts over $100. Some states have installed perks guidelines, of varying strength. And the drug companies' trade association, Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), even pulled back.

"There is a huge misperception that the industry 'wines and dines' physicians," said Rick Chambers, director of Worldwide Communications for Pfizer Inc, by e-mail last week. "In fact, the industry clamped down on these practices six years ago when it became clear that they were creating false impressions of exerting undue influence. At that time, the industry created a code of conduct that bans entertainment and any 'leave-behinds' that are not patient-focused. Pfizer embraces this code. In fact, if an employee is found to be willfully violating the code, it is grounds for termination.

"The code allows for such things as modest lunches or snacks as part of our informational programs. That's because we realize that the health-care professionals who participate in these programs are using their limited time, and in such instances providing refreshments is appropriate."

Nevertheless, this past fall Congress introduced legislation that would make drug companies disclose how much they've spent on gifts to medical practitioners.

Big Pharma's spending hit the news repeatedly over the past year:

In April 2007, the New England Journal of Medicine published results of a study that found that almost 95 percent of physicians in this country have a freebies- or payment-receiving relationship with the drug industry and that 83 percent welcome free food and 78 percent take free drug samples.

On May 11, 2007, an article in the San Francisco Chroniclediscussed the PharmFree Scorecard. It's based on a survey by the American Medical Student Association which graded universities on their freebies policies, and apparently Stanford and Davis have some of the toughest rules against drug rep influence.

A Nov. 1, 2007 New England Journal of Medicine article, "Doctors and Drug Companies — Scrutinizing Influential Relationships," talked about attempts by Congress and some states to force drug companies to disclose the amounts they spend on gifts to physicians. For example, the Physicians Payment Sunshine Act, introduced by a Republican senator from Iowa and Democrat senator from Wisconsin, would require disclosures from drug manufacturers who rake in more than $100 million a year.

In a Nov. 25, 2007 article in the New York Times, "Dr. Drug Rep," Dr. Daniel Carlat told of how he was sucked into the drug-peddling profession by flattery and big bucks from the pharmaceutical company Wyeth, traveled about giving talks about the new antidepressant Effexor, believed everything he said, and then gradually began to discover that the new drug had some problems he could no longer ignore or downplay. As he was required by Wyeth to say only nice things about the drug, he lost faith, saw the light and gave up the cush life of a drug rep.

A Jan. 2, 2008 news story from Reuters reported on a study, to be published in the February issue of American Journal of Public Health, that concluded that free drug samples more often go to well-off, insured people than to low-income and uninsured folks.

On Jan. 7, 2008, Science Daily reported that "the U.S. pharmaceutical industry spends almost twice as much on promotion as it does on research and development." The story follows a just-released study by New York University researchers Marc-Andre Gagnon and Joel Lexchin, who said that in 2004 the industry made $235.4 billion in sales in this country; 24.4 percent of that revenue went back into marketing, and 13.4 percent went into research and development. Big Pharma collectively spent $57.5 billion on drug marketing — about $61,000 per physician, according to the study. (The researchers note that the trade group PhRMA contends the industry spent more on R&D in 2004 ($29.6 billion) than it did on promotion ($27.7 billion).)

Dr. No

Eureka Family Practice employs four physicians and three mid-level practitioners. Dr. Leer's been there since 1994. For much of that time, and long before, he had no beef with drug reps. "I haven't always been pure," he said.

In fact, he got his first stethoscope from the drug company Eli Lilly, in med school. He went to USC from 1980 to 1984, and at that time drug reps roamed the halls uninhibitedly. "I remember walking in one day and every one of our mailboxes had a stethoscope in it," Leer recalled. "And I thought, 'Oh, how cool.' What did I know? It was normal."

At his current practice, he said, there used to be two to three drug rep lunches a month, and other times coffees, pastries and cookies. And he's gone to fancy educational dinners and accepted other free meals. "Remember when Gonsea opened?" he asked. "Shortly after it opened one drug company did a deal where you could call in an order for the take-home dinner and all you had to do was you would stop on your way home and pick it up."

He wasn't immune to the occasional drug company-sponsored trip, either. "Probably the most smarmy thing I did was a little fly fishing junket to the Redding area to a couple of private resorts," Leer said. And there was a fishing trip on the lower Klamath River, too. The funny thing about both of those junkets, though, is that Leer can't remember the name of the drug companies or their reps.

Even so, he says there's "no question" he was influenced by such gifts. "Especially when I was less experienced. Drug reps are by and large very intelligent, very nice, very good-looking people, and they work hard on getting a personal relationship with you." When it came time to choose between drugs to prescribe, he says, he might have subconsciously thought of a recent free lunch he'd had and decided to try "that nice guy Joe from Merck's" new drug.

So, what's wrong with that?

"It's unethical," Leer said. "It's got nothing to do with education, it's got nothing to do with really trying to help. It's all marketing. And it just seems dirty and smarmy and immoral. The thing is, all those silly little perks, and the lunches, aren't intended to produce immediate results. You know, the rep doesn't expect me to go out and immediately that afternoon write a prescription for his or her newest, most expensive drug. But it's intended to produce a sense of gratitude and a favor-done kind of thing. And truly, there have been enough studies now that it's incredibly clear that ... physicians who accept those things write more brand-name subscriptions for the drugs that they're detailed on."

Unlike many providers, Leer doesn't view samples as simple charity. "By and large, a sample of a given drug class or type isn't the best first choice for a patient," Leer said. "You know, drug reps don't leave us samples of penicillin, which is still the drug of first choice for strep throat. They leave us samples of the newest and most expensive antibiotic. So if I see somebody with strep throat, I'm probably tempted to give them samples if they don't have much money or whatever, or I just want to make life easier on them, so I say, take these samples. Which does a number of bad things. One — perhaps the biggest thing with the example I'm using — is, I'm giving somebody probably a very broad spectrum antibiotic that breeds resistant bugs and leads to our antibiotic resistance problems, rather than the narrowly targeted penicillin that does just as good a job or probably better for strep throat. Most of the time, there's a generic that's just as good or better."

Over the years, Leer's grown increasingly skeptical of the pharmaceutical industry, especially its claim that it costs more than $800 million to produce a new drug. "The vast majority of new drugs are developed in government-subsidized university programs and ... the government sells their right to the drug to a drug company," he said. The drug company then spends money marketing it. And sometimes, it's not pushing a true "new" drug, said Leer, but what's called a "me-too" drug — like Lipitor, a drug used to lower cholesterol, which has taken the brand-name place of Nevacor which has now gone generic. Lipitor costs more and is touted as better. "They're in the exact same class of drug, they do the exact same thing in the exact same way, but they're different chemical structures."

With the me-too drugs, Leer said, "the drug companies maybe spend $10 million doing a small study to prove their drug is safe, and then they spend hundreds of millions marketing it."

An article in the January-February 2008 issue of the AARP Bulletin notes that between 1996 and 2004, the amount drug companies spent marketing directly to providers soared 275 percent: about $7 million a year in perks, and about $18 million in drug samples. (The data comes from The Prescription Project).

"The problem is, most physicians when asked say, 'No, I'm not influenced,'" said Leer. "But also, the vast majority of physicians believe that other physicians are influenced. Figure that out. There've been a number of studies on this."

Drug rep

It would have been wonderful to have a drug rep tell it like it is. From the sound of it, it's an itinerant lifestyle, wearying but exhilarating. High-paying. And social. But for all their friendliness, drug reps clam up when reporters call. Oh, if you're a doctor phoning in, they'll be hitting speed dial. The Journal called 19 of them, most of whose names and numbers came from a two-inch stack of business cards that a pharmacist gleefully handed over, and who were mostly based in Redding and Santa Rosa and places like that. Two numbers were disconnected — must've moved on. The rest called from the stack went straight to voice mail, and only one called back to say to contact her company directly, as drug reps don't talk to the media.

One long-time locally based rep whose name several doctors dropped — he's well-liked — answered his phone. But he said that because he still does contract work for drug companies, he preferred not to talk. He was really nice about it. Another guy whose name came up often was ready to spill all but then backed away, most likely after realizing the error of his inherent generosity.

But a call to Pfizer produced quick results. Rick Chambers firmly, and on short notice, denounced all the mud-flinging.

"Pfizer and other pharmaceutical research companies have an exceedingly important role to play in disseminating new information about medicines and appropriate use of them," said Chambers. "In fact, over the years doctors have told us how much they appreciate the information we provide. And that need is increasing because the complexity of our products is increasing, more post-marketing studies are being conducted, physicians have more time constraints and thus fewer opportunities to catch up on the latest data, and consumers are becoming more engaged in their health care.

"As for marketing expenses vs. R&D expenses," added Chambers, "according to the Congressional General Accounting Office (GAO), the pharmaceutical industry spends about 50 percent more on R&D than on marketing. In a study a few years ago, the GAO found that the industry as a whole spent about $30 billion on R&D and about $20 billion on marketing and advertising. About half of that $20 billion is accounted for by the free medicine provided to doctors...."

Dr. Yes

Harris and Harrison. This is the corner that anchors the Eureka neighborhood where you go if you're feeling poorly. Or if you want to stave off that event. Or if you're pregnant. Between (roughly) Ramone's Bakery on Harrison and that corner, and then maybe about a quarter mile in either direction on Harris, plus down some plump side streets along the way, you can find what you're looking for: a family practice provider, opthamologist, cardiologist, radiologist, neurologist, gynecologist, psychologist, phlebotomist, podiatrist, pharmacist — whoever.

One office that gets a wide variety of traffic in particular is one of the Open Door Community Health Center branches, the Eureka Community Health Center on Buhne Street just off Harrison. On a recent Friday at noontime, a drug rep happened to be hosting a lunch for the clinic's staff and providers inside the meeting room of the Telehealth and Visiting Specialist, also part of Open Door and across the parking lot from the clinic. There was a reminder of the lunch inside the clinic's front office, in red pen on a small whiteboard on a wall visible to anyone checking in at the main counter: "Applebee's drug rep lunch 1/18!"

Amy Nelson, a certified med tech and in charge of handling drug reps at the clinic, seemed rattled that a journalist had shown up just as the lunch was about to begin, asking about that very thing and requesting, spur of the moment, to sit in on the lunch. She conferred with someone about it, while a nicely dressed man bearing literature talked with staff as they wandered in to grab a plate and load it with modest, yummy looking fare: salad, a small burrito or maybe the chicken-nugget-like things, and the like. Many of the staff, dressed in their scrubs and some with stethoscopes around their necks, filled their plates and walked out to return to their desks, while others stuck around.

In the end, the journalist wasn't allowed to sit in on the lunch. And Nelson didn't want to say what company the rep was from. But she agreed to an interview. "I think that Big Pharma and drug reps in general get a bad rap," Nelson said. "But people don't realize the philanthropical side."

First, there are the free drug samples that the drug reps drop off — not to be sneezed at at a clinic that sees a lot of people who can't afford pricey drugs. Second, the big drug companies like Pfizer, Merck and GlaxoSmithKline offer patient assistance programs for low-income and uninsured people; so, even if a patient gets started on a sample of a new, expensive drug, and eventually has to procure a prescription for it, she or he can sign up for assistance. Nelson helps people do just that.

"The drug companies are spending millions on the patient assistance programs, where they send the meds for free directly to the patient or to the clinic," she said.

As for the free lunches, she appreciates their quick, educational value.

On a day prior to that particular drug lunch in Eureka, Frank Anderson, a registered nurse and Open Door's director of telehealth development, explained the clinic's philosophy regarding reps and freebies. "Our goal is for the relationship with drug reps to benefit the low-income, safety-net patients as much as possible," he said. "And we feel that if the drug companies want to promote their products, and part of how they do that is by feeding, our policy is, don't just feed the doctors, who make more money. They have to feed everybody. It's a nice morale booster."

On another day, by telephone, Dr. Bill Hunter, the chief medical officer for Open Door, said each of Open Door's clinics have their own policies about drug reps, and each would have to speak for itself.

The Journal didn't hear back from the NorthCountry Clinic in Arcata by press time. The other Arcata clinic, Humboldt Open Door, does allow in drug reps and gladly takes the drug samples, said administrator Jay Molofsky last week. "About 30 percent of our patients pay out of their own pocket, so samples is an important aspect of what we do in the Open Door system," Molofsky said. He added that while the clinic accepts free pens and pads and the like, the clinic still buys its own office supplies. And, he wanted to make clear, providers and staff attend the drug luncheons on their own, unpaid time, at noon. "Everybody has to eat lunch," he said. "And, our providers have a healthy skepticism."

Hunter, who mainly works out of the Eureka clinic on Buhne but travels to the other sites, said he doesn't mind the drug reps. "I don't mind talking to them," he said. "I don't mind taking their pens. But I don't want to talk to them if I'm with a patient."

He said there probably is some influence going on with the samples the reps leave. "The thing is, it's really changed in the last couple of years. There's been a whole lot of drugs that have gone generic." These include some of the most-prescribed classes of drugs, ones for lowering bad cholesterol and treating high blood pressure and diabetes. You can go to Target, for example, and buy a generic drug for $4. Psych meds, on the other hand, are still branded, Hunter said, and therefore expensive. Nevertheless, he sees value in the drug samples.

"It's useful, you can try a patient on a new drug," he said. "I sort of go back and forth. I think all of us feel ambivalent. We always talk about the risks of getting your medical education from drug reps. So we encourage our providers to read peer-review journals, and they're required to do CME [continuing medical education] training, and there are the local 'grand rounds'" — local meetings held once a month for local medical professionals. Some of these meetings and training sessions do get sponsored by drug reps, he said.

As for the free food, for the most part it doesn't bother him. Except the fancy dinners.

"I don't like those," Hunter said. "I worry about those a bit more. There tends to be a risk there that the presentations aren't balanced, that there is a bias."

Lobster and Combigan

So what about those dinners? Are they some mythical relic of a more abundant past? After all, PhRMA, the industry trade group, frowns now on dinner attendees bringing their families along. And the speaker has to provide a more balanced presentation, rather than overtly discussing just the company's product. Still, a great deal of expense goes into putting one of these dinners on, which critics like Leer would say just adds to the cost of a drug or a new piece of medical equipment in the long run.

And yes, they do go on in this area — often at the swankiest place in town, Hotel Carter's Restaurant 301 in Eureka. Several Mondays ago there was a drug dinner there. The speaker, a pharmacist, presented information on Combigan — eye drops made by Allergan Inc. that treat "elevated intraocular pressure," a condition that can accompany glaucoma. It's a "new" drug, combining two already existing meds, that came on the market in late 2007.

Thirteen people, mostly opthamologists, attended that dinner, said 301's manager, the jovial Bob Graves. It's a typical head count for these things; between 10 and 15 people usually attend. "We probably do one every two weeks," Graves said. "In the year I've been here, we've probably done them for 10 different companies." About a month before the dinner, the drug rep will set it up with Graves. And then, on the arranged date, "dinner will start at 6:30. We'll serve the first couple of courses, and then we'll delay the main course while they have their meeting and slides."

Graves said the drug company hosting the dinner usually will spend around $75 per person. "And that's tip and tax and wine and dessert and entrée and appetizers," he said. "So it's a big chunk of money."

Not that Graves is judging anyone. "It's informative for the doctors," he said. "There's new drugs coming up all the time. And the paperwork that comes along with the drugs — doctors would spend so much time reading.... This way, they get someone who knows the drug. Sometimes they're researchers. So it's actually a pretty good deal. I don't think the doctors go there for the free food. They're paid enough to come here anyway. It's just incentive to get people to come. And they can visit with their coworkers. And doctors like nice places."

That said, Graves says he realizes these dinners must add to the price of a new drug. But over time, he reasons, that drug will go generic and be cheaper. "And basically they're just trying to help others," Graves said. "It's not like they're stealing, or polluting. They've gotta grab the ear of the doctor, and it's not easy to do."

Taking the pulse

A random sampling of medical practices reveals a mixed bag of responses to the question of drug reps.

At Cloney's Pharmacy, on Harrison, head pharmacist and partner in the business Rich Spini — who happened to attend the Combigan dinner — says that as long as a drug rep's presentation "isn't blatantly biased and has good academic info," he's for it.

Pharmacists don't get as many freebies as doctors' offices do, he said, although they do visit a lot and drop off business cards, pens, pads, sometimes coupons for medications to give to customers and, on rare occasions, maybe a pizza.

He shares some of Dr. Leo Leer's concerns, however. "I think the samples are the problem," Spini said. "I know when they drop off a lot of new drug samples, often doctors will start a patient on it. And often it's not the best medicine. There may be drugs in the same class that are a lot cheaper."

At a cardiologist's office in Eureka, the front desk person, who asked not to be identified, said "the doctor doesn't take samples or talk to reps."

At Eureka Ob-Gyn Associates, Dr. Deepak Stokes took a moment to explain why they keep the perks to a minimum. "The problem we have in Humboldt County is we have a lot of people who are underinsured," he said. "The question is, how does the physician prevent himself from being taken in? For us, our reputation is how you treat, not what you're giving out as samples. The gold standard is, the patient comes first. I have a very fine line: I don't like to use a medicine when it first comes out. I like to see how it plays out in the marketplace."

North Coast Opthamology accepts drug rep goodies. So does the Center for Women's Health, on Harris: True Martin sat at the front desk one recent Friday, dressed casually in a bright yellow sweatshirt — the office is officially closed Fridays, but one doctor was in taking patients. Martin, wrangling with endless insurance paperwork, said the reps come in dressed to the nines. "Oh, please," she said. "It's like the UPS — they're all tall, dark and handsome, and dressed professional. And the women, they're in pantsuits, or skirts and blazers."

Martin said she's always wondered why the reps bring food. She'd let them in anyway.

"We have one drug rep who comes in and always asks, 'So, what kind of coffee do you like?' It's nice that they ask. They always throw luncheons, too — that's another nice thing they do." But pastries are out: "One doctor here is health-conscious, so she put a stop to it. Now they bring granola bars. And they bring fruit baskets, and pens and pads. I always assumed they get a budget for that. But then, they're really so nice, I figured maybe they pay out of their own pocket. But why would they do that? They're already coming in. They bring us massive samples.

"I think they do a wonderful service to the community."

Fortuna Family Practice? Yes to drug reps. An Arcata practice? One doctor says yes, another says no. St. Joseph's Hospital? No. St Joe's spokesperson Kevin Andrus says drug reps can't visit anyone without the pharmacy director's permission, and they can't leave samples or much anything else. "That's mostly because of the DHS [Department of Health and Human Services] and the Joint Commission that provides our accreditation," he said. "They can leave pens and some minor perks, but we typically decline those because we don't need another pen and we don't need another coffee mug and we don't need another scratch pad. If the rep violates the rule, they are banned from the hospital. That has happened several times."

Same story at United Indian Health Service's Potawot Village, in Arcata. No drug reps allowed.

At Eureka Pediatrics, Dr. Emily Dalton seems unfazed by the freebies question. Her office lets the reps in and takes samples. "We kind of see it as a patient service," she said. They also accept goodies. "I'm sitting here eating a breath mint out of a box from the company that makes Xopinex," Dalton said. "It's a form of albuterol [an asthma rescue medicine]. It's a couple years old. They're shaped like little inhalers.

"But they don't send us on trips to Hawaii. I think the companies have cut back on perks. I was trying to get a sponsor for a volleyball team but the drug companies wouldn't do it. Sometimes they'll bring a lunch for the staff. It's a little advertisement."

Dalton said she reads the medical journals and attends conferences — including expensive ones not funded by drug companies — and makes up her own mind about new products. "The drug reps have their job — I don't think you'll find a scandalous story here. We are a capitalist country based on free market and enterprise. I think it would be unreasonable to expect them to spend all that money on research and development and not be allowed to market it. Maybe in an ideal world there'd be a better way to disseminate medication."

Alternatives

Dr. Leo Leer wishes more providers would reach for that ideal. For his part, he's joined the website "No Free Lunch," a forum for people who want to get away from the influence of drug companies; on it, providers can sign a pledge not to accept freebies. Another site, Pharmed-Out, similarly educates providers.

Leer also has stopped the AMA from selling data on his prescribing patterns to pharmaceutical companies (the AMA gets it from pharmacies). Opting out was an onerous multi-step process, Leer said, but worth it if just to eliminate the ick factor. "I remember when we were still seeing drug reps, and I wanted samples of a particular brand-name asthma inhaler," he said. His office's default, he said, was to always prescribe a generic if it was available. "But it's nice to have samples for when somebody comes in with an asthma attack — we can treat 'em and send 'em home that second with a sample." The drug rep refused. "She said we weren't prescribing enough of the brand name so she wasn't going to leave us any samples."

Some states are helping physicians in their rebellion against such tactics. Pennsylvania, according to an article in the current AARP Bulletin, has started something called an "unsales force" of trained, non-industry funded drug reps who go around visiting medical practices educating providers about all drugs — new, old, generic.

Ultimately, Leer said, changing the way Big Pharma does things will take legislative action. "If the pharmaceutical companies didn't have the sway over the industry the way they do now, drugs — all drugs — would be cheaper. They're cheaper in every other first world country in the world and pharmaceutical companies are still making a living. For instance, Canada's national health system negotiates directly with drug companies for rates." But here in the U.S., as written into law by the Bush Administration, Medicare can't negotiate prescription drug prices with the companies. "We have take the price they give."

In the meantime, Leer said he'd like to see some local action — maybe a "little formulary for free drugs, that are generic, that every provider can offer" to patients, Leer said. "Open Door would be the logical place to do that, because they get so much federal money. But they also get so much free stuff they like from the drug companies."

The question of freebies remains, for the most part, an individual decision. "I think, frankly, physicians should do the moral thing and step back from the influence," said Leer.

more from the author

-

From the Journal Archives: When the Waters Rose in 1964

- Dec 26, 2019

-

Bigfoot Gets Real

- Feb 20, 2015

-

Danger at McCann

A kayaker's death has raised safety questions about low-water bridges

- Feb 19, 2015

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023