[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

The Old Tomlinson Ranch, July 2006. The Wilsons had slept hard, exhausted by their two-day journey up from Ojai and the fiasco they'd had with the moving truck. The truck was too tall to pass under the bridge that crosses over the road at Lady Bird Johnson Grove, and they'd had to bring in a bunch of smaller trucks to unload their stuff into.

Just once in the night they had been startled awake by a most unusual sound: silence. They lay awake a moment, marveling at the deep quiet and the masses of stars shining outside their big windows, and Judith felt that little restless tumbling in her mind, which had plagued her for years, suddenly slow and then come to rest. She smiled, and dropped back into slumber.

But at dawn a sound like horses tromping through the house awoke her and Lavere again, and they stared about their new bedroom at first, confused. When they looked out the window, there were Garland Graves' cattle, clomping around the property and bumping into the porch, snuffling for forage.

It was their first morning in their new home and it felt, thought Judith happily, like they'd really traveled back into the Old West.

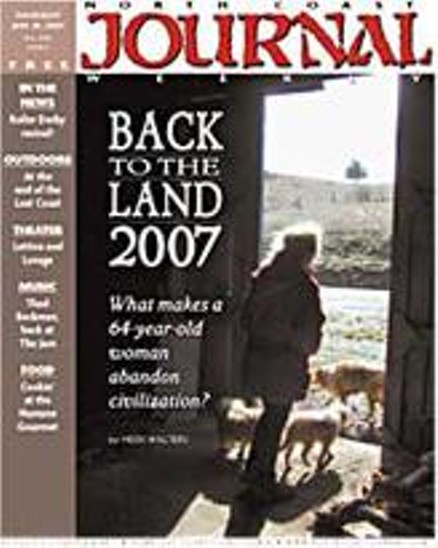

Hard Welcome.In July 2006, Judith and Lavere Wilson moved from Southern California to a gracefully sprawling, two-story home in the Bald Hills - a former stage stop and hotel. It was built in 1922 by Kiah Tomlinson on the sheep and cattle ranch run by his dad, George Tomlinson. The hotel, long since converted into a house, looks pretty much as it did in its youth, except with fewer trees around.

The ranch sits on one of a series of grassy ridges flanked by firs and redwoods, 15 miles from Highway 101 by way of the twisted, potholed mosaic of pavement, gravel and dirt called Bald Hills Road, which leaves the highway just north of the tiny burl-stop of Orick. If you followed Bald Hills Road past the Tomlinson Ranch gate, after another 15 miles you'd hit Weitchpec, where the Trinity River joins the Klamath - almost the middle of nowhere for some people, and close to the center of the world for others. Mule trains carrying mining supplies once negotiated the Bald Hills to get to the mining camps, followed by horses and stage coaches once an official road formed. The Tomlinson place became a regular resting place midway.

The stage stop is almost a thousand miles and nearly a century from the Wilsons' former home in Ojai. They have one neighbor, Garland Graves, a cattle rancher who lives maybe a mile away on the ridge to the west. He's the one who sold them the property - his brand, a G inside a circle, is everywhere, including on the front door and in the bathroom. The rest of their 190-acre property is flanked by Simpson Timber Company land and Redwood National and State Parks.

The place is about 3,000 feet above sea level and subject to snowstorms and summer heat waves. The house is off the grid and relies on a combination of wood, propane, solar panels and a generator for heat, cooking, lights and running water. They rarely turn on the lights. Once a week, someone -- usually Judith -- tromps out to the wood hut covering the well and yanks on a pully several times to start the pump that sends water up the hill to the water tank. From there, the water makes its own way back down the hill via gravity to supply the house. But the water's undrinkable, so they haul drinking water in bottles from the water shop in Arcata on their stocking-up trips to town.

During their first six months they had no hot water for bathing, except what they could boil up in a pot on the gleaming, white, 1920s-era propane Wedgwood stove. And, just as winter descended, the Wilsons, unused to wood-getting and still learning the ropes, got caught without a good supply of dry wood. So the big stove in the main room of the old hotel - the handsome, black, 10-foot long wood-fired iron cookstove from an old steamship that normally would heat up the whole place - sits cold most of the time.

There is no telephone, unless you count the stuttery cell phone service that only sometimes works. Stormy weather can render the road out of there impassable, or at least very scary.

Judith is 64. Lavere is 69. Their three dogs aren't puppies any longer and one of their cats is an orange "old man" of 22. What are they doing here? Why retire to an old, off-the-grid ranch house a-toss on the high redwood prairie? With just one neighbor a ridgetop over for company, unless you count the wind, rain, snow, heat, ticks and fickle road? And why not just move to a smaller town? Or a simpler town, like Arcata?

Well, in Lavere's case, "he can live anywhere," is how Judith puts it. And Judith? It's like she's finally come home. And that's why this is her story.

Ojai 2005.The neighbors were fighting again. Their shrieks and bellows penetrated the walls of the neighboring Wilson house, jangling Judith's nerves. She sighed. She'd worked all day, giving people massages at the Oaks at Ojai health spa, and then driven through the nasty SoCal traffic that clogged even this pretty, hilly, celebrity-riddled town of 9,000 not far from Santa Barbara. Tomorrow would be a full work day in her home office, taking Rolfing clients. Now she just wanted to be able to sit down and relax. But how could she with that racket next door? It didn't just annoy her, it made her feel deeply unhappy.

It wasn't just the yelling. Any moment her drunk neighbor could come stumbling out his front door, naked as a jay again, and run raving down the street. Or there'd be another drive-by shooting. Or someone could get raped - that had already happened right across the street, in broad daylight. It was insane. Might as well be in the middle of downtown New York. She couldn't walk around the town at night like she used to - not safe. Heck, not even in the day: One time she was attacked by pit bulls, and another time she permanently damaged her hand protecting Goodwill - Willy, for short, one of her refuge dogs - from a vicious akita.

And she'd about given up on that nice trail nearby. Those wealthy ladies with their spoiled pooches hadn't seemed to figure out yet how the city-provided doggie-do bags worked, and the path had become treacherously foul. Not to mention she'd become crossways with most of them over it.

Sitting on the couch and petting Willy on his shaggy head, Judith - a slender, blue-eyed woman with graying blonde hair piled on her head - sighed again and thought about that book on tape she'd recently listened to. Angle of Repose, it was called. By Wallace Stegner. He'd won a Pulitzer for it in 1971. It was about a man, slowly dying of a paralyzing bone disease, holed up in his grandmother's house in Grass Valley and going through her boxes of letters and personal effects to write a book about her life. His grandmother, as a young woman, had been thick with the artist and literary set on the East Coast in the 1860s, but then had married a mining engineer and followed him West. They lived amid squalid camps and, for many years, perched in a shack in a desolate canyon. It's an uneasy tale of casting off civilization and intellectual pursuits for adventure, duty and hardship - and the difficulty his snobbish grandmother had in reconciling with that sacrifice. It's also about harsh, beautiful landscapes that seep into the bones. "Angle of repose" is an engineering term that refers to the angle between the slope of a pile of similar-sized particles - grain, fine sand, rocks - and the horizontal surface the pile is on. Different particles come to rest at different angles. The key is, they come to rest. But it's a rest that can be easily upset - any movement, and the grains might slide, or even avalanche. Stegner's characters used the term metaphorically, of course, for their own restless, peace-seeking lives.

"That's what I need," Judith thought. "I need to find my angle of repose."

The neighbors burst into a new tirade, bringing Judith back to Ojai. "I've got to get out of here," she said, for the millionth time.

Judith.Friends tell Judith she should write a book about her life. "I don't know why," she said. "I don't think it's that interesting, but they do."

She was sitting in my pickup and we'd just closed and locked the gate to the property and were now pointed down Bald Hills Road toward the highway. It was Jan. 10, 2007, and I'd come up to see the old stage stop and meet its new owners. Before I came up, I had agreed - in a patchy cell phone conversation whose connection took Judith six tries to achieve from her lonesome hilltop - to give her a ride back to Eureka when we were done visiting. Her Prius was in the shop, having been towed away from the ranch the day before because it wouldn't start. This was strike two against the Prius since they'd moved into the hills. On another visit to the mechanic, after a part had been recalled, Judith had been told that her car wasn't cut out for rough roads, and the beating it was taking showed. And now, this time, it turned out to be a dead battery. "They told me I'm not driving it enough," she said. "There is a thing called a Smartkey, and so, being electrical, it runs down the battery just sitting. Plus, it's got an alarm system on it. The Smartkey, you just have to walk up to the car. You don't even have to use a key to turn on the motor, as long as you have this Smartkey, which is just a little square box. You can get in and go. It's a wonderful car. I highly recommend people owning one."

Except, of course, if they live up Bald Hills Road. As we drove along a ridge that dropped steeply to either side - panoramic vistas all around - Judith said she was thinking about buying a pickup. Good for hauling stuff. And it would be one more twist to make her friends and family giggle.

"I have a brother in Kansas. He's older than me - he said he's going to visit. He just laughs: `I can't believe you're doing this. I would never do that. It's just too hard, I want it easy. I want to walk into a room and flip a switch on. I don't want to have to put logs on the fire.' Alex. He likes luxury cars."

Her daughter also laughs. "She said to me, People ask me about you, Mom. You've always been strange. You don't retire into a nice community - you know, a retirement community. You retire into the late 1800s where it's hard work.' I just laughed. I said,But that's where I'm happy.'She thinks I'm crazy."

Judith grew up in the little prairie cowtown of Clayton, N.M. From the start, she was different. "I was thought to be autistic when I was quite young. I didn't walk or talk for a long time. As I have studied autism in later life, I find I do have some symptoms of Asperger's." Although she feels compassion toward others, she has trouble connecting with most people, she said. "As a child I was very, very withdrawn. My father called it melancholia."

By age 15, Judith had married the boy next door. By age 16, she was a mother. Skip ahead to an assortment of adventures: In college she majored in history, then changed to anthropology. She became a Baptist, and then a deacon in the church ("I'm a recovering Baptist," she said). She owned a health food store. She divorced, then married the assistant dean of a graduate school in Colorado. She modeled for boutiques and newspaper ads. She worked out at the gym a lot. She studied other religions, Buddhism. "Any human being that I felt did good work, I always wanted to look at what religion they were studying, how they got their values." She did transcendental meditation.

She remarried again, to Lavere, a chiropractor and neurologist. And, along the way, Judith found her passion for body work.

"My father was a chiropractor, so I was just around people who had pain, who had MS, who were on crutches, or whatever, all my life, and I was drawn to it," she said. "I wasn't drawn to adjust bones, per se. But I always had a knack of touch. So, I've been trained in Rolfing, in massage, in Thai massage, hot rock massage. I do Reiki. It's energetic healing - it's hands-on healing. It's the stuff you read about in the Bible."

After 35 years in Boulder, Judith moved with Lavere to Ojai. Boulder, once small and charming, had grown crowded. She thought Ojai would be tamer."I fell in love with Ojai, years and years and years ago, in the '70s, when it was also charming," she said."I would go back every year and hike the mountains. It was a place where I could be quiet. But it changed. I moved there thinking it would be the same, but it wasn't." So she worked and saved to get out. Somewhere.

She found it one day, more than a year ago, flipping through a real estate magazine while visiting a friend in Bayside. "I saw this ranch, and it was exactly what I've always wanted - a big wraparound porch, and there it was. I said, this must be my home. I didn't even see the land, I just saw the structures. My husband and I came out a year ago December to see it. And he fell in love with it. And it was pouring - it was pouring and the wind was blowing, and he still fell in love with it."

She told me about listening to Angle of Repose on tape. How this "repose" at the ranch was what her heart had yearned for. But, I said, it sounds like living at the stage stop requires a lot of hard work.

"It is a lot of work for an older person to live in the city," Judith countered. "The traffic, the noise, the drive-by shootings, the stress. But this - this is just heaven." She fell quiet. Then said: "To me, the angle of repose is not physical. I don't think of it in physical terms, I think of it in emotional terms. I mean, I can be doing hard, physical work, but I'm still at my angle of repose up there. Inside."

At the highway we turned south. As we drove through redwood forests, over lagoons and next to crashing ocean, she said even the long haul into town pleased her.

"Sometimes I think of the Louvre, and I think of these wonderful museums and these beautiful structures," she said. "But I've been to Europe already. So, it's OK. I've got it in my head. Besides, look at this structure. It's incredible. It's all so beautiful."

At home.The clock, tick-tocking in the downstairs main room, chimed 7. It was still dark out. Inside, the faded pictures on the walls were barely visible: romantic prints of a cabin in the forest, a fisherman hoisting a net, a sailboat cleaving the sea and two Currier & Ives pieces, "Winter in the Country" and "Barnyard in Winter." In a bowl on a chair in the kitchen, several lemons and a paperwhite bulb glowed in the half light. Upstairs everybody was stirring. The dogs padded downstairs to be let out, and Judith threw on layers of clothes, warm socks, boots and her bright red parka and followed. She went out to the big barn, the three Wilson dogs plus a fourth, Garland's black dog Rose, accompanying her just like they did in the house. She lifted the long wood poles aside that brace the door shut, and heaved the sunbleached wood slab aside to enter the dusky barn. There, she bent to gather up some of the scrapwood lying in a heap on the floor.

Pitiful pile of corners and shavings - what she needed was logs, not this kindling. But this pile had saved them. When they bought the ranch, Garland Graves had told them they'd never need to worry about wood. He'd keep them supplied. But he got sick, and now he was in the hospital. Then winter bit, hard. The Wilsons didn't worry - they had an offer of wood from a man in the area. But that fell through. Judith frantically called a young man in McKinleyville, and he drove up two cords of wet wood that wouldn't burn. Desperate, she scanned the want ads, and one entry leaped out: "Dry Wood, Now." She called him, and the man - bless his heart - drove up in the middle of the night with a truckload of dry scrapwood. It cost $240. But it burns.

Now they knew better. Never get caught without wood. She looked around the barn - there, across the floor, lay the heavy rounds of tree she'd scavenged from the side of the road after a fire crew went through, tidying things up. She'd bought a chainsaw recently but didn't know yet how to use it. Then there was another pile of green wood some friends brought her. It should be cured by next winter. And she had already stacked the wet wood all around the house on the porch - took her all day. It'd be dry, eventually.

"Poor Garland," she thought. "I wonder how he's doing?"

She went back to the house and started a fire in the Wedgwood in the kitchen, and stoked the coals and added sticks to the modern wood stove in one of the smaller, cozier rooms. She filled the dogs' water and got out some organic hamburger from the propane refrigerator to feed them, raw. She nibbled at something organic herself. If she didn't have to, she wouldn't eat at all. Cooking's a bother, leaves such a big mess.

Then she started cleaning the other mess left daily by four furry dogs and the "old man," the orange cat - a second cat, a meanie who has torn chunks of flesh and fur from the orange cat, is, by decree, an outdoor cat now. All the while, Judith ticked off in her head the various projects looming in the future: Learn to use that chainsaw. Get more solar panels. Get a backup generator. Buy a truck. Clean up that bullet-riddled TV on the side of the road up the hill, and the abandoned batteries and other toxic trash lurking in the blackberry bushes by the wood corral. Clear out some of the blackberries. Plant blueberries. Plant a garden, maybe near the apple, pear and nut trees by the house. Buy some animals for a "knitter's herd" - some different kinds of sheep; an alpaca would be nice, but pricey. Learn to use the new spinning wheel and start whittling away at the bundles of wool she got in Colorado. Get some chickens. Plant oaks - this land used to have more trees. Try to get someone up here to put in rain gutters - seemed like no one wanted to make the drive. Meditate. Just be in the moment - "Be Here Now," as Ram Dass says. And then maybe drive into Orick to see if the latest Netflix assortment has arrived at Hagoods Hardware - they're so kind to let UPS drop the Wilsons' packages off there. (No, they don't watch TV or do computers at the Wilson ranch, but they do on occasion like to eke out an evening movie on their stored solar power.)

Later - no packages - Judith returned home, and she and the dogs set off for their daily jaunt. Come sun, rain, snow, hail, wind - staying away from the trees in storms, like Garland told them to - or masses of ticks in the summer, they walked. Today, temperatures were again dipping toward freezing and the sky was such a cold hard blue it could crack. She couldn't hear the creek running down by the pond, but after a good rain, oh, the lovely sound of it! Between that and the wind in the firs lining the road in front of the house... Well, she'd said it before: This place was heaven.

They walked up the dirt road wrapping around the property - the old stage route went this way - and toward Williams Ridge. But they wouldn't go onto that pretty mountain. Judith already got in trouble once for venturing onto Simpson land, back when she didn't know better. She could wander into the Park, if she wanted to. Those park service guys, and the fish and game guy, too, had been so nice after the Wilsons moved in. They'd driven up to the house to welcome them and offer assistance - anytime, anything.

Judith and the dogs walked all afternoon, passing at one point a herd of elk, and into the early evening, Judith's hatless head on fire with cold and the dogs' noses and paws freezing. Returning in the dusk, Judith thought fleetingly of mountain lion. She wasn't afraid of bears - she'd seen one ambling up the driveway last summer. And she'd lived in lion country before, in Colorado. She respected them, and always carried bear repellent and a whistle on her walks, just in case. But she'd never been bothered by a lion. Maybe she and the mountain lion had some sort of agreement, she mused.

Night came, sharp, cold. The moon was up, a waning mass. It reminded her of the night that guy brought the scrapwood up. It had snowed in the day, and walking back to the house from the barn, in the moonlight - it was just breathtaking.Settling in by the wood stove in the cozy room, Judith got out the new course on astronomy she'd ordered and started studying the constellations.

The sky here was fabulous.

We checked in with the Wilsons on Tuesday to see how they were weathering the cold snap. Judith said the pipes had frozen and burst over the weekend, and the water pump appeared to be broken. So, she's been trudging down to the pond, breaking the ice, and hauling water in a bucket up to the house for bathing and cleaning. "It's pioneer," she said. But on a brighter note, they've just received a truckload of dry pine logs to burn.

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1

more from the author

-

From the Journal Archives: When the Waters Rose in 1964

- Dec 26, 2019

-

Bigfoot Gets Real

- Feb 20, 2015

-

Danger at McCann

A kayaker's death has raised safety questions about low-water bridges

- Feb 19, 2015

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023