[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

He's been obsessing over it for half an hour. Standing motionlessly under a lightproof shroud, Vaughn Hutchins peers through his wooden, 100-year-old Empire State No. 1 view camera, tinkering with tiny changes and contemplating every compositional detail. The accordion folds protruding from his cloak keep the lens at just the right distance from the antique camera's 11-by-14-inch ground-glass viewfinder. In front of him, Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park unfolds its old-growth glory. Broad shafts of light spill out of the canopy's opening, highlighting the crinkled cloth of a redwood's bark. After perfecting his composition he steps back, opening the shutter. Over the next few minutes, a giant negative will soak up the light, capturing the scene with incredible detail.

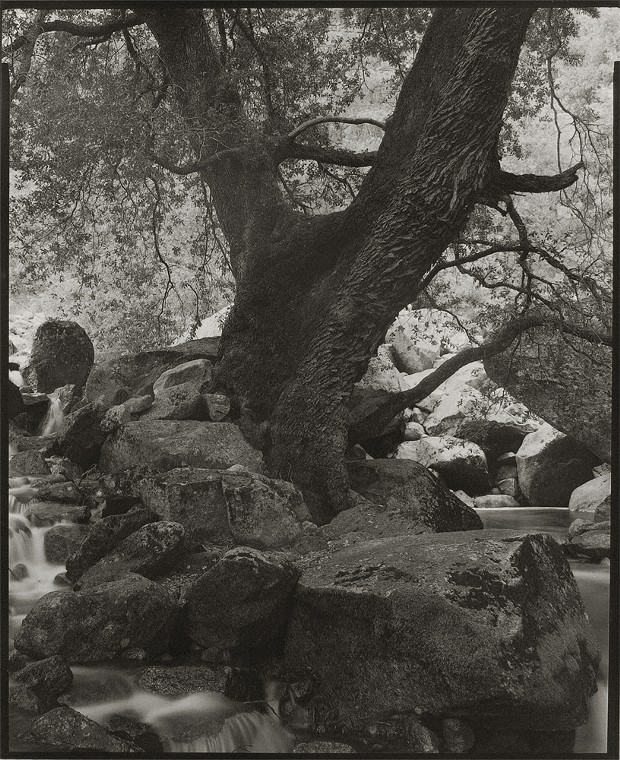

Vaughn Hutchins' photographs encapsulate the spectacle of our natural world with an enlightened clarity. Sweeping diagonals of water and rock alongside stout vertical trees and cliffs lend both movement and stability to his photos. To stand in front of one of his landscapes is to feel like you're looking out the eyes of a wild creature.

Hutchins' strong form, silver beard and tanned features clearly mark him as an outdoorsman. After graduating from Humboldt State University in 1981 with a natural resources management degree, he went to work for the Forest Service building trails, counting fish, cleaning campgrounds and spending lots of time outside. These experiences formed the core of his relationship to the environment. More importantly, they left time for his other passion, photography.

With winters off, he'd head back to HSU and volunteer in the dark room. "I had to take a unit of extended education so I could be a 'student'" he jokes. Eventually, Hutchins became the photo lab technician, quitting his Forest Service job to focus on his photography and raise his triplet sons.

As a stay-at-home dad, Hutchins needed to find a method for printing photos that didn't require a dark room. He had time to experiment, so he tried something he'd read about in a magazine, a method invented in 1864 called carbon printing.

Unlike traditional silver nitrate photo processing, with its many chemical-laden steps, carbon printing is deceptively simple. Once Hutchins selects an ultra-large negative to print, he sets it aside and begins working on a "tissue." He adds water and black charcoal pigment to un-flavored, food-grade gelatin, heats it to the right consistency and carefully pours it over a sturdy sheet of plastic.

The gelatin-carbon tissue sits for a few days, after which he paints it with a thin layer of ammonium dichromate, "the only real nasty chemical in the whole process," warns Hutchins. Then comes the negative, which is laid directly on top of the tissue. UV light from a grow lamp passes through the negative and activates the ammonium dichromate. This hardens the gelatin-carbon mixture on the tissue, with the most intense areas of light creating a thicker amount of gelatin and deep, rich blacks. Areas of very little light don't harden. Eventually, the tissue is squeegeed onto thick, white paper and the whole thing is bathed in hot water. The water binds the gelatin to the fibers of the paper, the unhardened gelatin washes away and the plastic backing from the tissue is finally removed.

What emerges is stunning — a vintage-looking photograph with incredible crispness and an almost three-dimensional quality because of the different thicknesses of gelatin. If you ran your finger over it, you would feel where the black areas are built up higher than the white areas. It's also extremely permanent. "Gelatin is one of the most stable organic materials, while carbon is the most stable inorganic material," says Vaughn. Will the image bleach over time, even in direct sunlight? "I've never seen a lump of coal go gray yet!" he says with a laugh.

Perhaps the most sought-after quality of carbon prints is their tonal range. While most cameras' sensors are only capable of capturing either shadow or highlight detail, carbon prints have nearly the same sensitivity as a human eye. In the shadows, as well as the highlights, every detail emerges.

For Hutchins, carbon printing compliments his conceptual approach to photography. Using old cameras and antique procedures forces him to train his eyes and look for contrast and subtle intricacies of light. Unlike his digital counterparts, Hutchins can't touch up a photo to perfection, so he looks for shots that emphasize the shapes that light forms. It could be the way a sunlit stream wreaths a shadowy tree, or a zigzag pattern snaking up the metal girders of a bridge. The interplay of light and shadow — and every shade of gray in between — is almost more important than the scene itself.

It's easy to enjoy Hutchins' photos for their composition and appealing subject matter, but Hutchins' extensive use of alternative printing techniques sets him apart. In the era of Instagram, Hutchins' work asks the viewer to slow down and appreciate the quality of a handcrafted image. To check out his carbon prints, platinum-palladium prints and bleached silver nitrate prints, visit Arcata Artisans this Friday, Sept. 13, for Arts! Arcata (reception from 6-9 p.m.). Vaughn Hutchins joins figurative painter Joyce Jonté and potter Loryn White as one of this month's featured artists.

Know about a witty, talented, or otherwise unique artist with an upcoming show? Give Ken Weiderman a head's up by emailing [email protected]

Speaking of...

-

Disaster Response, Crowley, Art in Piles and Salsas

Sep 7, 2023 -

NCJ Preview: Abalone, KHSU and Help in the Storms

Jan 15, 2023 -

NCJ Preview: Potter Plans, Measure S, Masks and Analog Art

Feb 12, 2022 - More »

more from the author

-

Porcelain Reborn

CR's group show honors the porcelain city

- Mar 5, 2015

-

The Prolific Hermit

Painter John Motian at Piante Gallery

- Feb 5, 2015

-

Perfectly Imperfect

Lauryn Axelrod's wabi-sabi vessels at Fire Arts Center

- Jan 8, 2015

- More »