|

COVER

STORY | IN THE NEWS | PUBLISHER | OPINION

DIRT | STAGE MATTERS | TALK OF THE TABLE | THE HUM | CALENDAR

November 10, 2005

story & photos by HEIDI WALTERS

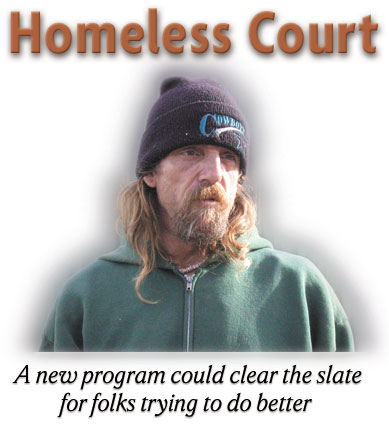

Above: After decades of working

hard labor jobs, Butch Henderson is homeless and jobless in his

home town. He recently was ticketed for riding his bicycle down

the wrong side of the street.

The 'bum'

BUTCH HENDERSON seems a bit

of a comfort magnet here at 35 W. 3rd Street in Eureka, where

a mix of homeless and working poor people are slowly gathering

this Thursday for the midday free meal provided by St. Vincent

de Paul. Henderson, dressed in a green sweatshirt, black jeans,

sneakers and a black knit cap with "Cowboys" stitched

in blue thread on it, stands alone in a puddle of pavement away

from the line of people forming against the building, talking

with Les Rastorfer, who's sitting on a bench. And as he talks,

people keep coming up to him for stuff. One young man, dressed

nattily in black, wants a cigarette. Henderson gives him one.

Another man -- a kid, really -- wants to borrow the striped,

multicolored hacky sack Henderson grips in his right hand. He

tosses it to him, following it with his eyes, then resumes talking.

Henderson, who is homeless,

and Rastorfer, a case manager for Mobile Medical (a health-care

truck that serves the homeless population), are discussing one

of the more plaguing aspects of the already difficult life on

the streets: The steady accumulation of police citations that

adhere to homeless people for infractions that range from peeing

in public to illegal camping to, for those who don't know about

the free meals, petty thefts of food and other necessities from

convenience stores. Why, just the other day, Henderson got a

double whammy.

Right: Les Rastorfer

is a case manager with the Mobile Medical Office, which brings

health care to people living on the streets. He says a pile-up

of petty fines can block a person from getting important medical

benefits.

"That day -- the police

were here all day, and they pulled a couple of people over who

were just driving by," recalls Henderson. "I was sitting

right here. I picked my pack up and got on my bike, and the cop

was over there on his motorcycle. I was going to the [Rescue]

Mission on 2nd Street to drop my pack off -- they let people

leave their things there during the day. So, I got on my bike,

and I went across the street and was riding to the Mission, and

the cop came after me." He was ticketed twice: for riding

on the wrong side of the street, and for having an outdated post

office box number on his driver's license.

"It's a total waste of

taxpayers' dollars," says Rastorfer. "There are house

break-ins in Eureka, and the police are busting people for riding

bicycles on the wrong side of the street. He's easy prey. The

police like going around these areas where the homeless are.

It's like shooting fish in a barrel."

The kid comes back and hands

Henderson his hacky sack. He looks at it gravely.

"I've been playing for

about four years," Henderson says. "It's something

out here that gives me space, because out here, it's hard to

have privacy."

Henderson has reddish long hair

and a short beard and mustache. His light eyes are a little sad,

his face prematurely drawn with long lines of a life hard-lived.

He was born 45 years ago, on Nov. 22, in Eureka, and he's been

homeless in his home town since 2000. Like many homeless people,

he sleeps down by the bay. "Before I came out here, I always

thought bums were lazy," he says. "But everybody has

a story of one kind or another. Working people pick on us all

the time. But it's not just that people are lazy. A lot of people

are not capable of working."

His story? He worked hard, body-breaking

jobs for years, 60- to 90-hour weeks sometimes, including 17

years with Eureka Fisheries. The jobs came and went. For 10 years

he lived and worked in Phoenix, where his brother lives. One

night, his house was burgled and the invader bashed in his face.

It was a turning point, and he came back to his home town. But

he'd been declining, physically, anyway. His legs and back ache

intolerably now and he finds it hard to get up in the morning.

Once while working a night job, he says, "somebody went

like this" -- he sticks his arm out straight, pinches his

fingers together and shakes his hand like he's holding a baggie.

It was meth, he got hooked, and life just got harder.

Still, listening to Henderson,

you get a sense he's on an upward swing. He's going to physical

therapy now, he's struggling to quit meth, and he has a "significant

other" he met a year ago. "Her kids call me 'Dad.'"

She and the kids are in the M.A.C. -- the transitional-living

Multiple Assistance Center -- and she has saved up enough money

for them to rent a place together as a family. "We're filling

out applications," Henderson says.

This is where the bicycle citations

could cause trouble, if Henderson doesn't deal with them. And

that's where a new concept, for Humboldt County anyway, could

come in handy. It's called "homeless court."

The law

Everybody, at some point, has

probably committed an "infraction" or maybe even a

misdemeanor. Riding a bike on the wrong side of the street, like

Henderson did. Or forgetting to update the address on that driver's

license. Maybe, even, sitting on a bench in public after drinking

a few. And every day, hordes of people -- housed and unhoused

-- let their dogs wander off-leash in the Arcata Community Forest.

Others let their dogs sit down in the Arcata Plaza (they're supposed

to keep moving). These are all citable offenses, usually dealt

with by an appearance in court and payment of a fine.

But some infractions and misdemeanors

might stem from the condition of being homeless, says Steve Binder,

a deputy public defender in San Diego who co-founded the nation's

first homeless court, in San Diego County in 1989. "Most

of the offenses the homeless folks bring into court are public

nuisance offenses," Binder told Michael Twombly in a taped

interview earlier this year. (Twombly is a board member of the

Humboldt All Faith Partnership, which runs the nonprofit, private

Arcata Night Shelter.) "They are the result of their being

homeless. They might be 'sleeping in public' or 'drinking in

public' or 'peeing in public' -- things we do in the privacy

of our homes, they do outside because they have no other options.

Additionally, you'll find petty thefts [of food], because people

might be looking to survive. Or you'll find people doing drugs,

whether it is a way of self-medicating or just a way of surviving

on the street. We're not trying to condone that." Rather,

homeless court tries to engage a person, with the community's

help, in finding a way out of the homeless situation.

Fact is, Binder reiterated last

week, most homeless people don't deal with the tickets they get

from the police, either because they don't have the money to

pay the fines, or they're afraid of being jailed so they avoid

going to court. As the tickets and warrants for failure to appear

in court multiply, their fears increase. Often, homeless people

will just tear up these pesky "notices to appear" or

shove them into the bottom of a backpack to be forgotten. And

then the citations become red flags to prospective employers

and landlords. Also, says Rastorfer, who helps people get medical

coverage, a simple citation, ignored, can keep a person from

receiving Social Security Insurance and medical benefits. "You

can go from $900 a month and medical coverage, if you're on SSI,

to nothing," he says. "I've seen a lot of people go

through a lot of misery over something that was insignificant."

For a person with diabetes, for instance -- a common ailment

on and off the street -- loss of medical coverage can even mean

death.

But in "homeless court,"

all efforts to get one's life back together are put on the table,

and the judge views those and usually says, "case dismissed."

Homeless court, says Binder,

takes "away the traditional court sanctions of fines, public

work service and threat of custody, and, instead, people receive

credit for the positive things they're doing to get their life

back together. Those can be attending AA meetings, or training

and searching for employment. And the judge has proof of that

up front. And when the court actually recognizes what that person

has done in the program, the person actually sees that it is

valuable." That boosts self-esteem. "Because, when

you get citation after citation, and people are telling you to

move on, you feel worthless."

Binder says he recognized a

need for an alternative way of dealing with homeless people and

their citations when he was just starting out in the public defender's

office. He noticed an endless train of minor offenses: "illegal

lodging citations, sleeping under bridges, sleeping on a sidewalk,

sleeping in a doorway or in a field or a canyon. There was no

place to stay, and there were not enough beds to house the homeless

folks. The shelters were turning away folks. And some of these

people would be standing there [in court] with their worldly

belongings on their shoulders." That, and a survey of homeless

veterans who showed their biggest need was resolution of outstanding

bench warrants, spawned the homeless court, held at first in

a handball court at the county's annual Stand Down for Homeless

Veterans -- a bazaar of social and medical services. "In

the first four years, 942 homeless veterans resolved 4,895 cases."

San Diego's homeless court now is held monthly, alternating between

two homeless shelters, for all homeless people.

Homeless court is an alternative

way for a homeless person to tackle minor but niggling legal

problems without having to face a fine-wielding, jail-threatening

judge in a traditional courtroom. (Charges of major offenses,

such as assault, drug dealing or domestic violence, would remain

the purview of regular court.) For example -- and Humboldt's

legal team is still working out the details -- if someone is

busted for being drunk in public, she might agree to go to five

Alcoholics Anonymous meetings and perform community service at

one of the homeless service facilities. Or if a homeless person

is cited for stealing food, he might agree to seek out a homeless

service facility and learn about where to get free food. If he's

cited for loitering, he might agree to enroll in a job-training

course.

Humboldt County's homeless court

is tentatively scheduled to hold its first session at 3 p.m.

on Jan. 13, a Friday, at St. Vincent de Paul in Eureka, and to

meet thereafter once a month, perhaps even in other areas of

the county.

The legal team The legal team

Left: Humboldt

County Judge John Feeney is looking forward to presiding in homeless

court, where defendants charged with infractions and misdemeanors

will be given credit for having completed programs aimed at bettering

their lives.

Judge Feeney, who presides in

Humboldt County Superior Court, Courtoom 8, was born and raised

in San Diego and says he has "been admiring their homeless

court from afar for years." So when Christina Allbright,

a deputy public defender in the main public defender's office,

and Tiffany St. Claire-King, an attorney in the county's Alternate

Conflict Counsel office, asked at a California judges' meeting

if any local judge would be interested in holding a homeless

court in Eureka, he was ready. In September, he went down to

San Diego to observe a homeless court. "I was impressed,"

he says. "In the traditional courtroom, the judge sits up

high and looks down on you. In the homeless court, the judge

was eye-to-eye [with the homeless defendant] and it was just

much more personal." The judge still wears a robe and is

attended by a bailiff, clerk and court reporter -- it's a real

court of law, even if the setting's relaxed, and the defendant

has the same constitutional rights as in a traditional court

setting. But, most important, nobody gets taken into custody

at homeless court.

"For the most part, the

DA and the defense attorney will work out ahead of time how the

case is going to be handled, and I'll likely call the case and

say what the disposition's going to be," says Feeney. "They'll

have, say, three months to do it, and then they come back with

proof they completed the program."

Feeney says he expects homeless

court to save the county money and time. It'll clear up old cases,

and likely keep some people from re-entering the court system.

Homeless court will be conducted by existing staff within normal

business hours, with court just being diverted once a month to

a homeless provider setting.

"The court -- we see this

as a community outreach to assist these folks," Feeney says.

He compares it to a successful pilot mental health court the

county had for four years, until state funds dried up, and to

the county's existing drug court. "Courts, in general, are

going more toward rehabilitation than the punitive, which is

good."

Feeney allows that homeless

court alone isn't going to eliminate homelessness. "Many

homeless people have substance abuse issues and mental illness,

and for those people it's more complicated," he says. "But

I think for some homeless people, they just need a helping hand.

The way I look at it, even if we only help 10 to 20 people a

year, that would be great."

Right: Christina

Allbright (right, foreground), a Humboldt County deputy public

defender, and Tiffany St. Claire-King (right, back), an attorney

with the county's alternate conflict counsel office, talk with

homeless Eureka natives Jody Kiesner (left, foreground), Robert

Wayne Printy (middle) and Chester Bighead (back).

Allbright and St. Claire-King

likely will form the core defense team for homeless court. For

St. Claire-King, it was at a meeting earlier this year between

judges, district attorneys, public defenders and law enforcement

to talk about the regular court process that she found the impetus

to push for a homeless court here. "Several law enforcement

officers expressed frustration about writing citations for people

without addresses, and then they would just get lost and nothing

would be done," says St. Claire-King. Since she had worked

with Sacramento County's homeless court, she knew enough to start

promoting the idea. Allbright was also at that meeting where

police officers told the judges that "people are just tearing

up tickets ... and the court doesn't even issue warrants sometimes

to people they've cited" because the people don't have addresses.

"I think [homeless court] is going to make the police happy,

because they'll get to see some accountability."

The cop

It might be tempting, at this

point, to wonder if maybe the police could just lighten up on

the homeless folks. But that isn't the way it works, says Arcata

Police Captain Tom Chapman, namely because the police don't distinguish

between housed and houseless people -- that would be profiling.

As Eureka Police Captain Murl Harpham puts it, "Our job

is to write the ticket -- just enforce the law."

That said, Chapman is willing

to produce statistics, upon request, based on types of offenses

-- again, not linking them to a person's housing status. This

year, from January to date, for example, the Arcata Police Department

issued 113 tickets for illegal camping within the city limits,

and seven tickets for urinating in public. Once a citation is

issued, the police department sends a copy of the citation to

the district attorney or city attorney's office, depending on

the charge. The person cited is supposed to contact the court

within 30 days to either enter a plea or pay a fine.

Binder agrees it isn't the cops'

problem. "I don't badmouth the police," he says. "They're

caught in the middle of a social problem, and they have to answer

to the citizens."

Still, the cops seem to like

the idea of homeless court. "Conceptually, I like the idea,"

says Arcata's Chapman. "How do we fine somebody $500, or

$1,000, if they have absolutely no means to pay? It makes no

sense." Harpham says the idea is "great." "At

least something will be getting done," he says. "We

had one guy who had about 60 tickets and he'd never been to court."

Equally frustrated have been

the homeless people who do happen to make it to court, says public

defender Allbright. Homeless court will give some of these folks

"doable consequences" as opposed to punitive consequences.

"We always tell people they should pull themselves up by

their bootstraps," says Allbright. "But we forget that

some people don't have bootstraps. This is going to give them

bootstraps."

The provider

The No. 1 bootstrap dealers

will be the homeless services providers, such as St. Vincent

de Paul, Arcata Endeavor, Arcata Night Shelter, Mobile Medical,

the M.A.C. and the Eureka Rescue Mission. Providers will refer

a person to homeless court and facilitate the process with the

legal team. Michael Twombly and Susie Van Kirk are board members

of the Humboldt All Faith Partnership, which runs the private

non-profit Arcata Night Shelter (the only emergency shelter in

Arcata), and likely will be at the forefront of the new court

program. Around about when the judges, attorneys and cops were

creeping up on the idea of a homeless court, Twombly was already

a few steps ahead of them. Twombly has worked with homeless people

and the mentally ill for more than a decade, and says he'd been

reading about homeless court when, one night, something happened

that convinced him it was needed in Humboldt County.

"I was driving back to

Arcata from teaching substance abuse courses at the jail in Eureka,"

he recalls. "It was dark, it was raining, it was cold. And

I picked up this guy. He'd been working all day -- he's a painter.

I said, 'Wow, that's hard to do without a car.' And he said,

'I got in a twist with a fix-it ticket for my taillight.' He

said he didn't pay the fine, and then he got cited again for

the same taillight. He didn't have any money to fix it. Then

he was issued a warrant. So, he couldn't get his car registered.

So, then he drove an unregistered car to work, and he got three

more tickets for failure to register. He owed $1,000 by then.

So then he stopped driving. And now he was hitchhiking to work

to feed his family. And I thought, there really ought to be an

amnesty day for this guy."

Twombly called Binder to talk

to him about San Diego's homeless court, and Van Kirk wrote to

Judge Feeney. Twombly went to San Diego to observe homeless court

in action, recorded interviews with Binder and another attorney,

then came back and joined forces with the players in the traditional

court system -- and Humboldt County's homeless court was born.

Happy ending

Everyone seems excited, but

perhaps no one is looking forward to homeless court more than

the mild-mannered Judge Feeney. His face shines when he talks

about his favorite moments of being a judge. "Weddings,"

he says, "and I really enjoyed running that mental health

court. It was just so gratifying to see people turn their lives

around." Yes, gentle Feeney, who says he loves being a judge

because he gets "to do the right thing," seems just

the right kind of judge to wander down to St. Vinny's for a Friday

afternoon clean-that-slate session.

"I feel empathy for folks

who, for financial, or physical reasons, or because of drug abuse

or mental illness, are homeless," Feeney says. "They're

no different from all of us. A lot of us could be homeless --

just one bad turn. This is going to sound corny, but I think

our community is only as strong as the less advantaged in our

community."

COVER

STORY | IN THE NEWS | PUBLISHER | OPINION

DIRT | STAGE MATTERS | TALK OF THE TABLE | THE HUM | CALENDAR

Comments? Write a

letter!

© Copyright 2005, North Coast Journal,

Inc.

|