Sept. 23, 2004

IN

THE NEWS | ART BEAT | STAGE DOOR |

PREVIEW

| THE HUM | CALENDAR

Ellen Thompson, age 8, from

Jacoby Creek School, poses for our cover with Scantron test scoring

sheet.

Photo by Bob Doran

Story & photos by HANK SIMS

Arturo Vásquez, superintendent

of the Klamath-Trinity Joint Unified SchoolDistrict, makes no

secret of his distaste for the Bush administration. [Vásquez in photo below]

Five minutes of small talk is

all it takes for the 57-year-old school official, a child of

immigrant farmworkers who rode a wrestling scholarship to a distinguished

career in education, to launch into his critique of the Iraq

war.

![[Arturo Vasquez in his office, Aztec mural and Native American watercolor behind him]](cover0923-arturovasquez.jpg)

But sitting at his desk in the

little district office behind Hoopa High last week, a few days

after his schools received their results from the state's annual

round of standardized tests, Vásquez saved his strongest

venom for President Bush's controversial education legislation

-- the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001.

"You know what No Child

Left Behind is?" he asked. "No Child Left Behind is

the government telling you that you have to get from Eureka to

Hoopa in two hours. And then telling you you have to walk."

![[Hoopa elementary School]](cover0923-hoopaelementary.jpg) Vásquez's bitterness is undiminished by

the fact that the Klamath-Trinity district's most troubled schools

-- Hoopa High and Hoopa Elementary -- did exceptionally well

on their 2003-04 tests compared to previous years. Scores at

Hoopa Elementary, where all but three of the 323 students are

classified as "socioeconomically disadvantaged," rose

by 5 percent overall -- one of the biggest gains in the county,

and more than enough for the school to make what No Child Left

Behind calls "adequate yearly progress." Vásquez's bitterness is undiminished by

the fact that the Klamath-Trinity district's most troubled schools

-- Hoopa High and Hoopa Elementary -- did exceptionally well

on their 2003-04 tests compared to previous years. Scores at

Hoopa Elementary, where all but three of the 323 students are

classified as "socioeconomically disadvantaged," rose

by 5 percent overall -- one of the biggest gains in the county,

and more than enough for the school to make what No Child Left

Behind calls "adequate yearly progress."

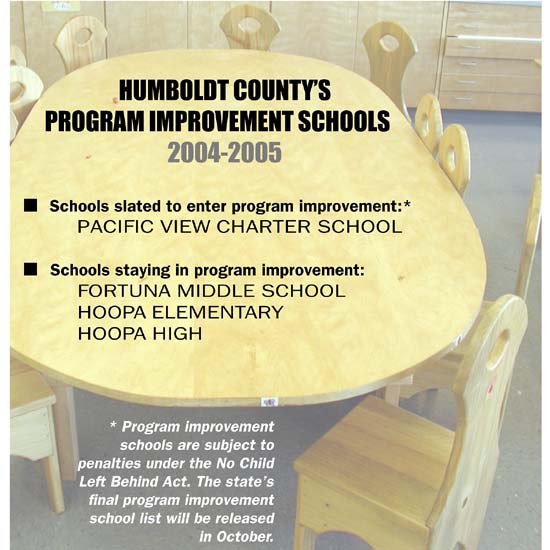

It was the first time in recent

years that both Hoopa High and Hoopa Elementary cleared that

hurdle. Despite the gains, though, both schools are still classified

as "program improvement" schools, meaning that they

are still subject to federal penalties under No Child Left Behind.

The schools will have to meet No Child Left Behind's goals again

this year in order to be dropped from the program improvement

list.

It's not that Vásquez

opposes standardized testing. Before he came to Klamath-Trinity

four years ago he built his career on "accountability,"

the educational movement that held that schools should be measured

and punished or rewarded on how well their students test. Accountability

swept throughout the nation in the 1990s, after several state

legislatures began to require it of their schools. As a consultant

to the California Department of Education in that era, Vásquez

worked with some of the most troubled districts in the state

--Los Angeles, Long Beach, Oakland -- to help them improve their

educational performance.

![[Hoopa Valley High School]](cover0923-hoopahs.jpg) Even today, Vásquez lovingly pores over

Klamath-Trinity's annual test results, taking satisfaction that

he can diagnose precisely where he needs to direct his efforts

-- to fifth grade math programs, maybe, or to literacy in grades

seven through nine -- to ensure that students get what they need. Even today, Vásquez lovingly pores over

Klamath-Trinity's annual test results, taking satisfaction that

he can diagnose precisely where he needs to direct his efforts

-- to fifth grade math programs, maybe, or to literacy in grades

seven through nine -- to ensure that students get what they need.

"It's like a doctor,"

he said last week. "You go to a doctor, they check your

throat, they check your stomach. They figure out where you need

the treatment."

But Vásquez, like many

educators, believe that No Child Left Behind, with its ambiguous

and ever-changing rules, its under-funded mandates, its zeal

to punish schools that don't live up to its standards, may be

doing more to harm troubled schools than help them.

"Accountability is what

I'm about," Vásquez said. "It's what I'm trained

to do. But has the government made its adequate yearly

progress? I'd say no. Words are not enough."

The

big stick

![[No Child Left Behind logo]](cover0923-nclblogo.jpg) As

the federal government's contribution to the accountability movement,

No Child Left Behind seeks to impose educational standards on

those schools that get money from the Title I program, a national

fund meant to aid schools with a high population of "socioeconomically

disadvantaged" students -- those who come from poor families,

or ones where the parents did not graduate from high school. As

the federal government's contribution to the accountability movement,

No Child Left Behind seeks to impose educational standards on

those schools that get money from the Title I program, a national

fund meant to aid schools with a high population of "socioeconomically

disadvantaged" students -- those who come from poor families,

or ones where the parents did not graduate from high school.

"Program improvement"

is a regimen of penalties intended to force schools to improve

test scores. If a school doesn't achieve "annual yearly

progress" -- a complex formula involving standardized test

scores, graduation rate and other factors -- for two years in

a row, it is placed on the program improvement list, and becomes

subject to immediate penalties.

Every day, for instance, Klamath-Trinity

buses Hoopa kids down to Trinity Valley Elementary in Willow

Creek because parents whose children would otherwise attend a

program improvement school have the option to send their children

to a school with higher test scores. The district has to pick

up the cost of the busing, spending money that could otherwise

have gone into teacher training, materials, field trips -- things

that could directly improve education in Hoopa.

"As it is, this district

puts in more miles than probably 95 percent of the districts

in the state," Vásquez said. "Do we get enough

money for that? No."

![[colored blocks]](cover0923-blocks.jpg) The school winds up with fewer students and receives

less money from the state. The school winds up with fewer students and receives

less money from the state.

All the while, Hoopa students

must achieve better scores if their schools are to avoid even

more severe punishment. If program improvement schools continue

to fail to achieve yearly progress, they can be forced to restructure

their school entirely by hiring all new staff, converting into

a charter school or turning over control of the school to the

state.

Poor overall test scores are

not the only way a school can make it into the dreaded "program

improvement" category. It only takes students from one grade

to fail to meet expectations in one subject for the entire school

to fail its annual yearly progress goals. In addition, "subgroups"

of students -- those who qualify for free lunch programs, for

example -- have to meet academic benchmarks.

Perhaps most worrisome to local

educators is the mandated participation rate in testing. To make

adequate yearly progress, a school must test 95 percent of its

students in each grade, and for each subgroup, even though parents

may withdraw their students from the testing process if they

do not approve of standardized tests -- a not uncommon occurrence

in Humboldt County. Several schools in Eureka nearly went into

program improvement this year because not enough students took

the tests.

"Almost all of those schools

that didn't make it last year, they didn't make it because of

participation rate," said Bob Munther, assistant superintendent

for the Eureka City Unified School District. "We had schools

that were 94.6 percent, 94.7 percent -- we thought, `Just round

up!' But they didn't round up."

Despite their high test scores,

two area charter schools -- Big Lagoon and Mattole Valley --

would be going into program improvement this year based on the

fact that too many of their students opted out. Their saving

grace is that they are among the few local schools that do not

take Title I money, and so are exempt from No Child Left Behind

requirements.

However, this year the act began

to apply to entire districts, in addition to individual schools.

So the Big Lagoon and Mattole districts -- which do receive Title

I money to fund their other schools -- may have to answer for

their charter schools' low testing rates.

Burdensome

requirements

But it's not just struggling

schools that have had to work to keep up with the provisions

of No Child Left Behind, especially in rural areas like much

of Humboldt County.

Cheryl Ingham [in photo below]

, program manager for school support and accountability at the

Humboldt County Office of Education, said last week that small,

under-funded districts require immense support in order to keep

current on all the act's requirements.

![[Cheryl Ingham in office ]](cover0923-cherylingham.jpg) "More and more, our little districts have

to rely on me," Ingham said. "It's become so complicated

that you're not going to have someone in-house to handle it." "More and more, our little districts have

to rely on me," Ingham said. "It's become so complicated

that you're not going to have someone in-house to handle it."

Not all of these are related

to test scores. For example, when it was passed the act required

that schools move toward hiring "highly qualified teachers"

-- though it neglected to specify what would make a teacher highly

qualified. Districts scrambled to divine the government's intention

on their own and to apply what it thought would be a reasonable

standard to their own faculties. The government only recently

clarified its intentions.

"It's taken a lot of staff

time to look at each individual teacher and whether or not they

meet each of these criteria," said Eureka Unified's Munther.

"Now, two or three years later, after we put in umpteen

hours" -- time that clearly could have been put to better

use, he said -- "it looks like we're going to make it."

Susie Jennings, associate superintendent

for curriculum and instruction at the Southern Humboldt Joint

Unified School District, said that it initially appeared that

the highly qualified teacher requirement would cause her district

a great deal of trouble. The regulations at first seemed to demand

that a high school math teacher possess a degree in that subject.

In small schools such as hers, where there is not a large enough

student body for a full-time math professor, science teachers

often teach math as well.

The government recently issued

a clarification that would permit such an arrangement, but Jennings

said that she still spends a significant amount of time making

sure her school complies with this and other provisions of the

act.

"There were a number of

things in the law that made it extremely difficult for small

rural high schools," she said. "Some of those things

are getting cleared up a little bit."

Perhaps most of all, critics

say the government has been unwilling to provide funding that

would help schools to comply with the No Child Left Behind's

requirements. Last spring, the National Conference of State Legislatures

estimated that state and local governments would be spending

$10 billion more than the federal government budgeted for the

2004-05 fiscal year in order to fund No Child Left Behind. Estimates

of the total amount spent by state and local government since

the act was passed run as high as $27 billion.

A

taste of success

The accountability movement has its success stories.

One of them is the Rio Dell Elementary School District, which

back in 1999 did poorly on the first state standardized tests

under California's Public School Accountability Act of 1999.

Jeff Northern [in photo

at right] , a former first grade

teacher who today serves as principal of both Eagle Prairie Elementary

and Monument Middle schools in Rio Dell, helped coordinate the

turnaround. The accountability movement has its success stories.

One of them is the Rio Dell Elementary School District, which

back in 1999 did poorly on the first state standardized tests

under California's Public School Accountability Act of 1999.

Jeff Northern [in photo

at right] , a former first grade

teacher who today serves as principal of both Eagle Prairie Elementary

and Monument Middle schools in Rio Dell, helped coordinate the

turnaround.

Upon taking office, Northern

met with district teachers and devised a plan to revamp the schools'

curriculum so that it would match the state's educational standards

for each grade, in each subject. He sought out new instructional

materials to support the change. And he reorganized the district

so that seventh and eighth graders would have their own campus.

Reviewing the results of last

year's tests, released earlier in the month, Northern had every

right to be pleased at the program's success. Both have scores

better than the state average.

"I don't think we'll ever

have the highest scores in Humboldt County, but we'll be up there,"

he said.

Northern credits early adoption

of state standards as the key factor in turning Rio Dell Elementary's

schools around. By the time No Child Left Behind came into effect,

the district was already well on its way to improvement of its

test scores. The head start has allowed the district to escape

most of No Child Left Behind's punitive measures.

Still, Northern shares his colleagues'

criticisms of the federal law. "They've set impossible goals,"

he said. "Eventually, it's going to crash."

The stated goal of No Child

Left Behind is for every student at every school in the nation

to be rated at or above "proficient" in basic subjects

by the year 2014. Every year, more and more students in each

school have to score above a certain level on the tests -- the

broad definition of "adequate yearly progress" -- in

order to avoid punishment. Currently, the baseline is relatively

modest. But as it continues to rise, Northern imagines that even

excellent schools may not measure up to the act's idealistic

goals.

"It's a 15-year plan --

we're still in the early stages of it," he said. "It

doesn't seem that significant now. It's not to the point where

I'm terribly worried about it. But pretty soon, we'll all be

in the same boat."

![[Eagle Prairie elementary school in Rio Dell]](cover0923-eagleprairie.jpg) Some educators harbor a conspiracy theory that

the No Child Left Behind Act was designed to fail schools. If

enough public schools are deemed failures, the argument for school

privatization, whether through vouchers or the whole-scale outsourcing

of public education, is easier to make. Some educators harbor a conspiracy theory that

the No Child Left Behind Act was designed to fail schools. If

enough public schools are deemed failures, the argument for school

privatization, whether through vouchers or the whole-scale outsourcing

of public education, is easier to make.

Then there are those who simply

think that No Child Left Behind is a monumental mistake, or a

piece of electioneering grandstanding, that will inevitably be

scrapped when either it collapses under its own weight or a different

administration comes to power.

In the meantime, people like

Vásquez still must grapple with the act and take pride

in their victories. Hoopa's good showing in last year's tests

may have been despite No Child Left Behind, as Vásquez

believes, and not because of it. Still, he says, his teachers

have a new spring in their steps.

"People, when I got here,

found the school to be hopeless," Vásquez said. "Now

it's a different story. They've tasted success."

He only hopes that No Child

Left Behind -- with its unforgiving quirks, unfunded mandates

and subtle diversion of resources away from the classroom --

doesn't spoil it for them.

IN

THE NEWS | ART BEAT | STAGE DOOR |

PREVIEW

| THE HUM | CALENDAR

Comments?

© Copyright 2004, North Coast Journal,

Inc.

|