|

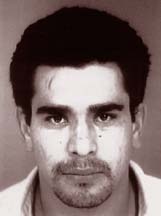

by LARRY GOLDBERG AT THE END OF THE TRIAL RAFAEL NOGUEZ LUNGED at us -- or seemed to -- shouting "I'm going to get you motherfuckers." Each of us felt as if he was attacking us personally; after all, we had just issued a verdict that would almost certainly send him to prison for the rest of his life. Minutes before, each of us had been individually polled, by name, as to our determination: first-degree murder for the killing of Jarliz Rivera [photo below left] , second-degree murder for the killing of Crystal Brantley [photo below right] .

After two weeks of jury selection, three weeks of trial (with testimony both boring and riveting), and approximately eight hours of sometimes heated deliberation, the facts seemed simple enough. Two murders were committed in Orick back in mid-2001. Rivera, a 26-year-old drug dealer known as Raul, was shot in the head and chest while sitting in his car and then buried in a shallow grave under a dairy barn. Brantley, 18, was killed a week or so later, also shot in the head. What did the two do to deserve such a fate? Rivera and Noguez were apparently embroiled in a drug-related dispute. As for Brantley, she wanted to go home after a night of snorting crank, or meth, but Noguez had to milk the cows -- his job when he wasn't selling drugs -- and didn't want to take her home. As far as we could tell, he was just tired of her shit, to use the vernacular. The discovery of her skull in an animal burial pit last year touched off the investigation that eventually led to Noguez' arrest. The remarkable thing was that Noguez, a 23-year-old Mexican farm worker, had committed almost perfect murders. Were it not for the fact that he told detectives about his crimes, he would still be a free man today. Without that, the skull might never have been linked to Crystal Brantley and Rivera's body would probably not have been found.

JUROR NO. 10 My experience with the case began on May 16 when I was called in for jury duty -- the third time in three years. The last jury I served on was more than 12 years ago: a drunk-driving case that took all of an afternoon to present and less than an hour to deliberate. For this trial, it took over a week to narrow a field of 300 down to 50 "qualified" jurors who were available to serve for up to a month and didn't have some immediate conflict like knowing one of the pending witnesses (a serious problem in a small community like Humboldt). A 10-page questionnaire gauged our attitudes about violence, drug usage, Mexicans, interracial relationships, the justice system and other subjects that might come up during the trial. I was selected as "Juror No. 10." What followed was three weeks of trial at the County Courthouse. The trial went from 9 a.m. to noon, with a 15-minute break around 10 a.m. The jurors got to know each other by their habits -- I brought homemade biscotti one day and was "Mr. Biscotti" from then on. One juror was building a summer home in the country and shared pictures and stories of the project. Another was an avid surfer who liked to go diving for abalone off Mendocino. A third worked at Jitter Bean Coffee Company in Eureka; we discussed her job -- satisfying "legal addictions" -- while walking by the bay on one morning break. The jury was mostly working folks, eight women and four men. Our role -- in the words of the prosecution -- was to be "the conscience of the community." Noguez had looked each of us in the eye when we were being selected and continued to do so during the trial. Since we couldn't talk with other jurors about the trial until deliberations, I learned later that several of the female jurors felt he was staring at them, and it made them very uncomfortable. I've heard it said that you can see the soul of a killer in his eyes, but all I saw was a deeply troubled young man who had made a mess of his life and ended the lives of two others. For three weeks, we listened to a variety of witnesses: Ballistics experts from the Justice Department; an anthropologist from the University of San Francisco skilled in the art of reconstructing a face from a skull; the director of the Haight-Ashbury Free Clinic in San Francisco, who testified about methamphetamine addiction. We heard how a hunter and his son found a skull in the pasture of an Orick dairy. We learned how authorities analyzed the skull, trying to figure out who it had belonged to and how that person had died. We were told that no fingerprints were discovered and that there was no DNA evidence linking Noguez to the crime. Criminologists taught us how ridges in the bore of a gun left identifying marks on bullets as they left the chamber. We were shown how pooling blood leaves a different stain on a surface than splattered blood. We were lectured about meth-induced psychosis, how methamphetamine affects the "primitive" brain and how most men get into dealing speed for sex, and only after dealing it become users (while women become addicts in exchange for sex). It was explained that different cultures use different drugs and although the message that "speed kills" is well known (it was coined by the Haight-Ashbury clinic in the late 1960s) its use is more prevalent now than ever -- especially in rural areas like Humboldt and Del Norte. We learned more about drugs and death than I ever wanted to know. FINE DISTINCTIONS To reach our decision we had to evaluate 28 pages of Judge Christopher Wilson's instructions, a mountain of evidence (including, in bio-hazard bags, the bloodstained carpet and pad from the car in which Rivera was killed), one of the pistols that Noguez used and most importantly the nearly one-hour, audio-taped confession that was recorded in the Lincoln County Jail in Oregon (where Noguez was incarcerated on unrelated charges). Due to the poor quality of the tape, we had to listen to portions as many as 10 times -- and even then, some people did not agree on what was said. Judge Wilson's instructions included specific definitions of murder ranging from manslaughter to second and first-degree murder. Voluntary manslaughter, what the defense was arguing for, meant essentially a murder committed in the heat of passion, but without malice. Second-degree murder is also a crime of passion, but one committed with malice. First-degree murder is a premeditated, deliberate killing. Cold-blooded, in other words. We were not allowed to keep our notes so these are not the exact words the judge used, but he basically said that the true test of premeditation is not the duration of time, but the extent of the reflection. Unconsidered impulse, even though it includes an intent to kill, is not deliberation and premeditation -- so it is not first degree. The issue is whether or not the person thought about it in advance. So one of the things we discussed was what constitutes premeditation. It was a relatively easy call to make in terms of the Rivera killing, since Noguez said on the tape, "When I saw him [Raul] in Fortuna, I knew what I was going to do." He mumbled a lot, but he basically said they met in Fortuna and went from there to his place in Orick to do some speed, "and then I got out of the car and shot him in the head and shot him a few times in the heart." The other killing was a bit different. Noguez and Brantley were at his place, probably doing drugs and having sex all night. A conflict developed when she wanted him to take her home and he needed to go to work. All that Noguez said that was clear on the tape was, "We had an argument, I came from my room with a gun and I shot her." We didn't know what his intent was at the time. At first I was convinced it was first-degree murder, but there was a reasonable doubt -- it could have happened in the heat of passion. It took some time, but eventually we all agreed. CONFESSION OR ADMISSION? But another issue remained. The defense had argued that Noguez confessed his crimes while he was in a psychotic state brought on by drug withdrawal. If that were true, then the evidence that raised the crimes above the level of voluntary manslaughter was unreliable. Which brings me to another distinction, between a confession and an admission. A confession, according to Judge Wilson's instruction, is a statement made by a defendant in which he has acknowledged guilt. To constitute a confession, the statement must acknowledge participation in the crime as well as criminal intent. An admission is a statement made by a defendant which does not by itself acknowledge his guilt, but which tends to prove his guilt when considered with the rest of the evidence. The defense's entire case rested on the testimony of psychologists who had extensive experience in drug-related psychosis. They suggested that Noguez was a habitual meth user with a borderline anti-social personality that led him to impulsive behavior and a lack of judgment driven by a fear of rejection and abandonment. They indicated that Noguez had a mental breakdown while in jail in Oregon, and that he was seeking professional help to stop disturbing dreams when he admitted to the crimes. In other words, it was suggested that he was not in his rational mind and that therefore his statement was invalid. Ultimately we decided that even if he wasn't thinking straight when he confessed, the fact that everything he said was supported by outside evidence more or less made the argument beside the point. The strongest evidence, of course, was that he knew where the bodies were. POSTSCRIPT After the verdict, and the outburst, the jurors walked into the hallway; most were sobbing and obviously shaken. While we had served together for nearly a month and had grappled with many difficult emotions, we had never encountered such direct evidence of Noguez' temper and explosive personality. We milled around briefly and one juror tried to pull us all together to share some closure on the whole matter. Unfortunately, the finale of the trial was so disturbing, most of the women of the jury just wanted to leave as quickly as possible and bolted for the exit. It was a disturbing ending to a sordid case.

Because of that incident, the whole time Noguez was on trial the bailiffs paid special attention to their sidearms and took extra precautions. He was always led into the courtroom with his hands handcuffed behind his back (generally they are in the front for most defendants) because they didn't want to take any chances with him going for one of their guns. We never saw any of this (it would prejudice the jury) because we were led into a full courtroom each day. It explained why five bailiffs where on hand at the end of the trial. Had he managed to get one of the guns at the end, it would have ended as a whole different story altogether. I also learned more about the background of Crystal Brantley. This was a very troubled woman with a sad, but all too common, past. She had been in the juvenile justice system for speed and had had a child within a few years of her murder. During the deliberations, several of the jurors wondered what had become of the child Crystal had. It remained a mystery for which we were given no information. As I walked back to my car after talking with Dikeman, all I felt was sad, tired and depressed. I felt like I needed a shower to feel clean again and some time to clear out my mind. Then something happened that shed more light on Crystal Brantley. I ran into a friend of 20 years who works in the juvenile justice system as a caseworker. She was outside her office having a smoke and asked what I was doing near the courthouse. When I said I had just finished serving on the Noguez jury, she told me she had known Crystal Brantley. Between my talk with her and what I learned from the D.A.'s office, I put the rest of the story together. It turns out that Brantley was a typical "throw-away" kid from Eureka. Her mother divorced and left her father while she was an infant and then essentially abandoned Crystal, leaving her in the care of a string of grandmothers, aunts and eventually shelters. She became, in all practical senses, a "wild child" who liked to party with Mexican men and hang out in the underground drug culture. She entered the juvenile justice system early on and did time in juvenile hall, where my caseworker friend got to know her. She was repeatedly told that drugs were going to kill her, but the warning fell on deaf ears. She had a child, fathered by a Mexican man with whom she was hanging out. She did little better than her own mother and eventually abandoned the child. When Brantley went missing, there was a warrant for her arrest for not checking in with her probation officer, but no missing persons report was ever filed because she led such a nomadic life -- no one knew she wasn't around. After it became known that she was dead (around March 2002) Brantley's mother tried and failed to gain custody of the child. Child welfare services stepped in and the court granted custody to a foster parent who is now in the process of permanently adopting the child. Hopefully this child will have a better chance at life than her mother did. Larry Goldberg is the president of NetHelp Now, a Eureka firm that supplies technical support services to Internet companies nationwide. He is also a member of Eureka Southwest Rotary. Editor Keith Easthouse and staff writer Bob Doran contributed to this report. IN THE NEWS | PUBLISHER | CALENDAR

Comments? © Copyright 2003, North Coast Journal, Inc. |

![Degree of Guilt - A juror reflects on the murder trial of Rafael Noguez [photo of Larry

Goldbert coming out of courtroom door, and inset photo of Noguez]](cover0703-photohed.jpg)

It

wasn't clear whether Noguez was going for one of the bailiff's

pistols or jumping out at us; in any event, panic engulfed the

room. The women of the jury screamed and then cried uncontrollably

as five bailiffs tackled the defendant and wrestled him to the

ground. It was, in the truest sense, the ultimate confirmation

of the process we had begun nearly six weeks earlier.

It

wasn't clear whether Noguez was going for one of the bailiff's

pistols or jumping out at us; in any event, panic engulfed the

room. The women of the jury screamed and then cried uncontrollably

as five bailiffs tackled the defendant and wrestled him to the

ground. It was, in the truest sense, the ultimate confirmation

of the process we had begun nearly six weeks earlier. As

it was, Noguez made things easy for the cops, and, frankly, less

agonizing for the jury. This wasn't a case where jurors had to

decide between innocence and guilt (Noguez' own lawyers were

arguing for voluntary manslaughter). The question instead was

how guilty was he? And that turned out to be a little tricky,

as the strategy of the defense was to cast doubt on the keystone

of the prosecution's case: the confession.

As

it was, Noguez made things easy for the cops, and, frankly, less

agonizing for the jury. This wasn't a case where jurors had to

decide between innocence and guilt (Noguez' own lawyers were

arguing for voluntary manslaughter). The question instead was

how guilty was he? And that turned out to be a little tricky,

as the strategy of the defense was to cast doubt on the keystone

of the prosecution's case: the confession. I

remained behind with one other juror to talk with the prosecutor,

Worth Dikeman [photo at

left] , and his investigator. They

shared some facts that we were not privy to during the trial,

such as that Noguez had had a similar outburst during an arraignment

in Lincoln City, Ore.

I

remained behind with one other juror to talk with the prosecutor,

Worth Dikeman [photo at

left] , and his investigator. They

shared some facts that we were not privy to during the trial,

such as that Noguez had had a similar outburst during an arraignment

in Lincoln City, Ore.