|

COVER STORY | IN

THE NEWS March 2, 2006

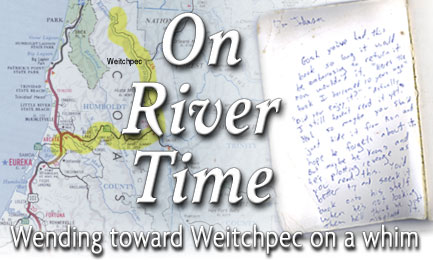

story and photos by HEIDI WALTERS THE BOOK I WAS DRIVING THROUGH THE YUROK INDIAN RESERVATION LAST FRIDAY TOWARD PECWAN, JOHNSONS AND THE END OF THE ROAD (as the road sign calls it), when I saw the book lying open in a shallow leaf-strewn turnout and pulled over. I could hear the loud shhhhhh of the Klamath River far below, and see it glittering in the late-afternoon light that filtered through the trees. The air was fragrant, like dried leaves and grass. Near my turnout was a dirt track diving down the steep embankment to someone's place along the river. I'd been following rivers all day -- up the Mad, down the Trinity, and now dogging the Klamath on Highway 169, which starts just past Weitchpec where the Klamath and Trinity rivers converge. There, Highway 96 (which travels north from Highway 299 at Willow Creek) veers northeast, and Highway 169 writhes northwest for 24 one-lane miles, then stops. At the End of the Road (Johnsons), the river continues another 20-some miles to Requa and the ocean. When I saw the book I had been driving slowly, mesmerized by the canopy of green over the winding road and wary of sudden crumbled patches where mud and rocks had tried to carry off the pavement -- it was a dizzying plummet to the river. Plus, every few minutes I encountered a string of big work trucks and had to squeeze over to the edge of the road or back up into someone's steep driveway to make way for them. Somebody -- or the wind -- had flipped the front cover of the book open, and I could see a handwritten scrawl in blue ink on the blank inside cover, just below a former owner's name, "Ron Johnson." It appeared to be the self-flagellating lament of a guilt-racked book borrower:

Poor guy. He must have been a serious victim of "river time." RIVER TIME

Another guy was supposed to meet me after that -- and he was an hour and a half late. I was starting to get the hang of this "river time." The most-late guy took me up to the Somes Bar Store [right] and showed me where to get a good view of the mountain that is the center of the world to the Karuk. Then, back at the store, I shopped for a late lunch (clearly, I was cut out for river time), and my guide whiled away minutes helping a friend hang some paintings. Time swirled into an enjoyable, vaguely fretful, eddy; other meetings, scheduled for way up the Salmon River, just weren't going to happen. So, a week later I decided to return to the region without a schedule -- to step into river time and not worry about a thing. I set aside my other business; maybe come summer I'd get to it, when the days are longer and warmer and I could camp. I made no appointments. I just pointed my pickup east and smiled at each construction zone roadblock. Happily I drifted -- getting sucked into more eddies, pinging gently off steadfast boulders, converging with others -- then at day's and road's end turned around to paddle back home. Being on river time, I discovered, made everything happen on time.

Around noon, just above the confluence of the Trinity and Klamath rivers, at Weitchpec (which means "confluence" in Yurok), I decided to stop at Bill Pearson's Grocery to buy some Weitchpec Chile Co. hot sauce for a friend who's leaving town. The store and a handful of outbuildings (including a restroom whose lock is a small rock you shove against the door with your foot), is all that's visible of Weitchpec from the road. A sign says Pop. 150, but I'm told more people live here: in the woods, off side roads, and down closer to the rivers. Inside I found owner Bill Pearson [right] and employee Alita Redner, working in the half-dark provided by a small generator while a repairman hammered away outside. Pearson just installed a big $15,000 generator, and the guy was "just switching things over." The store is a one-stop-shop: In one wing there's food, candy, magazines (many cannabis-related), sodas, beer, ice cream; in the middle by the counter is whiskey, cigarettes and ball caps; and in the other wing is a complete fishing supply counter with poles, hand-tied flies and other gear. There also are pocket knives, sleeping bags, playing cards, garden hoes, shovels, Crayolas, locally made jewelry, T-shirts ("Where in the Hell is Weitchpec" is a favorite, Pearson says), sledge hammers, auto supplies, lamp oil and hurricane lamp shades. "That was popular here a few weeks ago," Pearson said, pointing to the lamp oil. The power was out for almost a week after the big New Year's storm. But Pearson said sales of lamp oil increase every winter. And some people need it all the time, still: "See, we just got electricity in this area," he said. "Down the river, 24 miles where the road stops -- they just got electricity." Most of his customers are locals, and in the summer the fishing crowd comes in.

Pearson's dad, Eric, started the store. Pearson took over in 1955, the same year he got married. He and Barbara -- "She's the boss," he says -- just got back from a two-week vacation in Hawaii, and now they're getting ready to celebrate their 55th anniversary on March 18. Pearson points above the hot-dog case at a big plastic banner on the wall with a picture of him and his wife, framed in a big heart, and the words "Congratulations on your 50th Wedding Anniversary." Next to it is a football-themed beer poster and next to that a picture of an owl entangled with a snake that "a guy named Peter" painted for them. "Coors made that for us," he said of the banner. Underscoring the special relationship small, isolated stores in the wild backcountry form with their delivery people, a delivery guy rattled in dolly after dolly of beer -- 80 cases, in all. He delivers beer every other week, and another company delivers beer in between. Outside, the bread delivery truck had also just arrived. Pearson's dad was Swedish, his mom Yurok. "My mother and grandmother were born right across the river there, on the Trinity side," he said. He, too, was born and raised in Weitchpec. He took me outside to look down at where the green, clear Trinity meets the shallow, murkier Klamath. "The Trinity clears up quicker," he said. A flicker called from a tree by the store, and a diesel engine rumbled into the parking lot. Here's where he grew up, fishing and swimming, and where the three grandchildren he's raising are growing up. Something about Pearson's calm, gentle demeanor -- he speaks so quietly it's hard to hear him -- made me wonder if living here had something to do with it.

Is it a good life? "Absolutely," he said. "You've got everything you want. You want to go someplace, you go. You want to go fishing, you go fishing." You're not bothered by anything? "Nope," he said. "Day comes in and go out, you know." Back in the store, Redner told me she grew up here, went away to school, then came back when she got homesick. Her grandma was born here, and had nine kids, so Redner has a pack of aunts and uncles in the area. "It's nice, it's beautiful, it's quaint, everybody knows each other. And it's nice to be able to work here," she said. Her mom is a Head Start teacher for the Yurok Tribe, her brother does GIS survey work for the tribe and coaches basketball at Jack Norton Elementary School down at the end of Highway 169. Redner also works part-time for the tribe. "It's called the Brown Bag Program," she said. "Food for Elders. Every third Wednesday I go to Eureka and pick up cases of miscellaneous groceries, bring 'em back, break 'em down -- I have 23 clients -- and deliver a bag of groceries to each elder." I went outside and sat in my truck, jotting down notes. A van pulled up, and as he walked into the store I heard Redner tell him he should talk to me. So when the man came back out with groceries he came over to my rolled-down window and said, "Follow me." So I started my engine and followed Glen Pitsenbarger [below] -- owner of Weitchpec Nursery and creator of the hot sauce I'd just bought for my friend -- over the bridge, left onto Highway 169, and down the Klamath, mightier now that the Trinity had joined it. BACK TO THE LAND Highway 169 is a smaller road than the ones I'd just traveled, and just as high above the water. But it drops in elevation, gradually, from the 195 feet above sea level of Weitchpec. I turned on the radio, and Steve Earle was singing, "If I ever get home to Houston alive, I won't drive a truck anymore." We passed the sign that said "End of the Road, 18 miles," and not long after turned left onto Martin's Ferry bridge, where a sign said, "No stopping on the bridge. 10 ton limit." Pitsenbarger stopped in the middle and got out to lean on the railing and look downriver. I did the same. Straight down was a sandbar with three lines of footprints that converged at a rock.

Just then, on cue, shots rang from somewhere in the surrounding woods. "You hear that all the time," said Pitsenbarger. "Guys with nothing to do, sitting around shooting targets." A little creek runs down the mountain into the river by the bridge we were standing on, which was built in 1965 after the '64 flood washed out the one whose steel carcass inspired the shootout. "It's a cool place to sit at the top of in the summer," Pitsenbarger said, adding they'll usually have 30 days of over 100 degrees. We drove the rest of the way over the bridge, and turned right onto Tulley Creek Road. Had we turned left, we'd have eventually ended up in Orick. We passed more cascades and mossy springs, and soon were passing Yurok people walking along the road. A couple miles down, we drove by a community of new houses the tribe's just built. The road turned to gravel, and soon we turned left into the nursery. Just beyond, on the road we'd left, was the site of an old village at the Yurok center of the world. Weitchpec Nursery faces east, toward Burrill Mountain, and its grounds are abundant with sun-absorbing huge greenhouses. Inside each is a different story: flats awaiting sprouting, tiny seedlings, in-flower garden favorites like Sweet William, sprouting tomatoes, peppers -- everything. Pitsenbarger's six staffers mostly work the spring and summer months, during high season, although one is there all but one or two months a year. In a shed, Raymond Vader was prepping more soil,

and in a nearby greenhouse that smelled like dirt, candy (there

was a bowl of it on the table) and brewing coffee, Janice Olmo,

Lana Crutchfield, Billie Sue Coleman and Debbie Aguiar prepared

flats of seedlings factory-style. They laughed and kidded as

they worked. They've worked for varying lengths of time at the

nursery, but they all gravitated to the Weitchpec region about

Weitchpec Nursery workers Billie Sue "It isn't for everybody," she said. "I knew it was a hard kind of life. It isn't the norm. I lived in San Francisco. And down here, they didn't have electricity until last year. It isn't fun washing laundry in the creek anymore!" Olmo, who grew up in San Francisco and was friends with Aguiar, visited her frequently before finally, in 1977, moving here with her 1-year-old daughter. Crutchfield moved here in 1965. She's Yurok, but was raised in North Bend, Ore. They've all raised families here, and one by one ended up with a job at the nursery. Pitsenbarger came to the area from San Francisco

in 1970. He drove trucks there, mostly for Coca-Cola, and just

"got burned out on the city." So he fled to Humboldt

County, where he immediately started growing a beard and got

the gold hoop earring he'd pined for (but which former bosses

wouldn't Janice Olmo (left) and Lana Crutchfield The entire time, he's made do without being hooked to the electrical grid, just relying on gas and a generator. Last year, when the Yurok tribe put in power lines to supply the new homes out there, Pitsenbarger also finally got electricity. "What I'm waiting for now is telephone," he said, showing me the radio frequency phone that's fickle and costs him $450 a month whether he uses it or not. "They haven't hooked the telephone up yet, and I really want that. That's how I get orders for my plants from all the nurseries I sell to." Every Monday he drives to the Hoopa Valley to send faxes to customers. But there've been complications in getting the phone line extended out here. "PG&E put the poles down here and hooked up the power," Pitsenbarger said. "The telephone company came in and started hanging their lines, and they pulled the guylines on the PG&E poles, because PG&E hadn't installed them properly, and so the poles all tipped over. So now PG&E is replacing the poles. They had a big argument over whose fault it was that lasted about a year, but now I guess they resolved it. In a month or two I'll have a telephone here." We walked around the nursery, and in and out of more greenhouses, past Cocoa the shaggy dog, Bear the black cat and dirt-colored old Momcat sleeping on a shelf. In yet another greenhouse, Pitsenbarger introduced his wife, Gayle. "She's commonly known as 'Sis'," he said. "Only girl, four brothers," Sis said. So, I finally asked, what about the hot sauce? "I do those in Blue Lake, at a certified kitchen," he said. "The green and the red are kind of an unusual pepper, so I grow those. The habañero I make the orange sauce with, I buy those because they're cheap. They come out of either Mexico or Florida, for like $2.25 a pound, and I wouldn't pick 'em for that, you know. And they're a long-season crop, the habañeros." END OF THE ROAD After I left the nursery, I crossed back over the

big bridge and turned left, toward Pecwan. I felt compelled to

drive till the road stopped. I drove over bridges colorfully

painted with Yurok symbols and cartoon fish whose mouths bubbled

things like, "Got water?" Creeks waterfalled into the

river. I stopped to pick up a book lying open on the side of

the road. Lana Crutchfield's daughter A couple miles before Johnsons ("End of the Road"), I saw a family of five walking up the road. The little girl was sticking out her hand and making silly faces. I stopped to talk, and it turned out they were related to Lana Crutchfield, from the nursery, and were starting along the 20-some mile stretch to meet her partway. "We're going to Hoopa to see our dad," said Dana, the 4-year-old girl, while Tristan, 6, hugged their pitbull puppy named "Baby." Jeannette -- Lana's daughter and the kids' mom -- said she grew up here. "Everyone pretty much knows everyone around here. I usually know everyone who comes down this road." She lived in McKinleyville for 10 years, and just moved back here in August. It's the farthest down this road she's lived, but she said she's one of the few people with electricity, which she supplies through both solar-powered batteries and a back-up generator. "But it's hard not having a car out here." For her kids, it's all new. "Before our cousins moved here, Travis [who just turned 10] was miserable," said Alex, almost 12. "I love it up here. I get to chop down trees and climb trees. I've had a parakeet for almost a year come July. We have three dogs: Baby, she wasn't supposed to follow us. We also have a lab and pit mix, named Sissy. Travis, tell her about your dog." "It's half lab/half wolf, from Auntie Margo's brother," Travis said. I told them I was just going to drive the last two miles to the end of the road, and when I came back I'd give them a lift to meet Lana. So I drove to the end, where the land descends to meet the river and there's a broad, sunny clearing with a cluster of houses, a line of hood-up cars, and a little church. Just before it, at Pecwan, is Jack Norton Elementary School. Jeannette and her kids were in a wide turnout when I came back, and little Dana was making silly faces again and waving her arm for me to stop. She and I said "Aiy-yu-kwee!" a few times back and forth, Yurok for "hello." "They're learning it in school," said Jeanette. Then we were off. Several miles and bends later we encountered Lana, barreling down the road in her black pickup. "After you left," she said to me, laughing, "the girls all thought we should have had you take a group picture." PREFACE

Grit and bits of lichen fell from between its pages as I leafed through it, and then my eyes hit on a passage in the preface: "In the beginning and in the end was Nothingness. Nothingness implied the possibility of Somethingness. It is impossible to make something from nothing. Therefore, Nothingness could only imply Somethingness. That implication is the Universe is as straight as a string ... except for a loop at either end. We are wisps of that implication." It's the sort of circular jargon that attracts me when I want to lazily confront the Meaning of Things. And I've taken it out of context, so I'm sure he was implying something else, but to me the borrowed book, the preface, and even the beleaguered book-borrower's lament -- it all seemed to sum up the sort of day I'd just had: Wisping along an inevitable line (twisty, not straight) between loops of far-flung human outposts, into the heart of a green and wild, beautiful universe belonging to others. Expecting nothing except to find, at every turn, something. COVER

STORY | IN

THE NEWS Comments? Write a letter! © Copyright 2006, North Coast Journal, Inc. |

"River time"

is a phrase I'd learned the week before, and had adopted as my

mantra, after I'd traveled another direction into that mid-Klamath

region. I'd gone up to just past Orleans to talk to people in

Karuk country, arriving a half-hour late for my first meeting

because road crews had stopped traffic in three places between

there and Eureka to repair post-storm rock-slide havoc. But that

was OK, because the guy I was meeting was even later. Someone

mentioned "river time," jokingly.

"River time"

is a phrase I'd learned the week before, and had adopted as my

mantra, after I'd traveled another direction into that mid-Klamath

region. I'd gone up to just past Orleans to talk to people in

Karuk country, arriving a half-hour late for my first meeting

because road crews had stopped traffic in three places between

there and Eureka to repair post-storm rock-slide havoc. But that

was OK, because the guy I was meeting was even later. Someone

mentioned "river time," jokingly. GROCERIES

GROCERIES The

area also recently got phone service for the first time, although

it hasn't reached all residents yet. Other than that, Pearson

and Redner didn't have much news to report. Somes Bar Store,

up the road past Orleans, was burglarized on Feb. 3, according

to a "wanted" flyer posted on the bulletin board --

that's a first, said Pearson. It's been really cold, said Redner.

Oh, and the road crews are still cleaning up storm damage. And,

granted, "fishing ain't like it was," said Pearson.

"Everyone blames it on water shortage, you know. It's a

little bit of everything. Water's got a lot to do with it."

The

area also recently got phone service for the first time, although

it hasn't reached all residents yet. Other than that, Pearson

and Redner didn't have much news to report. Somes Bar Store,

up the road past Orleans, was burglarized on Feb. 3, according

to a "wanted" flyer posted on the bulletin board --

that's a first, said Pearson. It's been really cold, said Redner.

Oh, and the road crews are still cleaning up storm damage. And,

granted, "fishing ain't like it was," said Pearson.

"Everyone blames it on water shortage, you know. It's a

little bit of everything. Water's got a lot to do with it." So,

I asked, how'd the mud slides affect business? "Oh, you

learn to live by it," he said. They ran out of a few things,

"milk, bread -- when you run out, you run out."

So,

I asked, how'd the mud slides affect business? "Oh, you

learn to live by it," he said. They ran out of a few things,

"milk, bread -- when you run out, you run out." "See

that rusty A-frame over there on the bank?" he said. "They

were trying to salvage some of the steel from the old bridge,

oh, back in about 1975, or 1973. So, to salvage the steel, they

had to cut the bridge off at the river bed level. It was kind

of expensive, cutting under water, and the two guys who were

doing the work got in an argument and one of them shot and killed

the other one. So, one's in jail and the other one's dead. I

don't remember their names."

"See

that rusty A-frame over there on the bank?" he said. "They

were trying to salvage some of the steel from the old bridge,

oh, back in about 1975, or 1973. So, to salvage the steel, they

had to cut the bridge off at the river bed level. It was kind

of expensive, cutting under water, and the two guys who were

doing the work got in an argument and one of them shot and killed

the other one. So, one's in jail and the other one's dead. I

don't remember their names." 30

years ago. "My husband is Karuk, so his family is here,

and so we moved here in 1973 from Southern Humboldt," said

Coleman, as she used a special pronged board to punch holes into

the dirt cups in the flats. Aguiar, pulling tiny, individual

seedlings from a clump, placed each in the dirt holes of another

prepared flat. She said she moved here from San Francisco in

1974 to prove she could do it.

30

years ago. "My husband is Karuk, so his family is here,

and so we moved here in 1973 from Southern Humboldt," said

Coleman, as she used a special pronged board to punch holes into

the dirt cups in the flats. Aguiar, pulling tiny, individual

seedlings from a clump, placed each in the dirt holes of another

prepared flat. She said she moved here from San Francisco in

1974 to prove she could do it. condone).

In 1979 his friends asked him to caretake their place in Weitchpec.

He eventually bought it from them, and in 1983, began turning

it into what's now probably the biggest wholesale plant supplier

in Humboldt County.

condone).

In 1979 his friends asked him to caretake their place in Weitchpec.

He eventually bought it from them, and in 1983, began turning

it into what's now probably the biggest wholesale plant supplier

in Humboldt County. And

I kept running into more work rigs. Finally, I asked a guy in

an engineering firm's truck what's going on. "There's about

six different things going on out here on this road," he

said. "We're working for Caltrans. This place was surveyed

20 years ago, and we're just getting an update. PG&E's out

here, too."

And

I kept running into more work rigs. Finally, I asked a guy in

an engineering firm's truck what's going on. "There's about

six different things going on out here on this road," he

said. "We're working for Caltrans. This place was surveyed

20 years ago, and we're just getting an update. PG&E's out

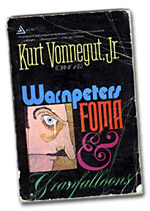

here, too." When

I got home I finally looked more closely at the book I'd picked

up from the side of the road to Pecwan. It reeked of mold. It

was a 1965 collection of essays by Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. Under the

fat yellow letters of his name was the disclaimer, in thin white

letters: (Opinions). Below that in blue, red, pink and

green words is the title: Wampeters, Foma & Granfalloons.

A painting of a man in profile, stylized, completes the cover

-- except, later, someone felt-penned a black "X" on

it.

When

I got home I finally looked more closely at the book I'd picked

up from the side of the road to Pecwan. It reeked of mold. It

was a 1965 collection of essays by Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. Under the

fat yellow letters of his name was the disclaimer, in thin white

letters: (Opinions). Below that in blue, red, pink and

green words is the title: Wampeters, Foma & Granfalloons.

A painting of a man in profile, stylized, completes the cover

-- except, later, someone felt-penned a black "X" on

it.